Before there was MAGA, there was MALGA—the Make Lexington Great Again movement, whose origins trace to the 2009 election of the MALGA Mayor Jim Gray.

There are any number of ways that the MALGA movement, like its MAGA cousin, has played a destructive role in this community. In this post, however, I will highlight MALGA’s urban design principals, most of which were copy-and-pasted from progressive national urban design sites like the Atlantic‘s Cities Blog and then dropped, SimCity like, into the fabric of our fair city through a combination of government subsidies, non-profit grants, saturation media coverage, supposedly intellectual inquiry and private business investment.

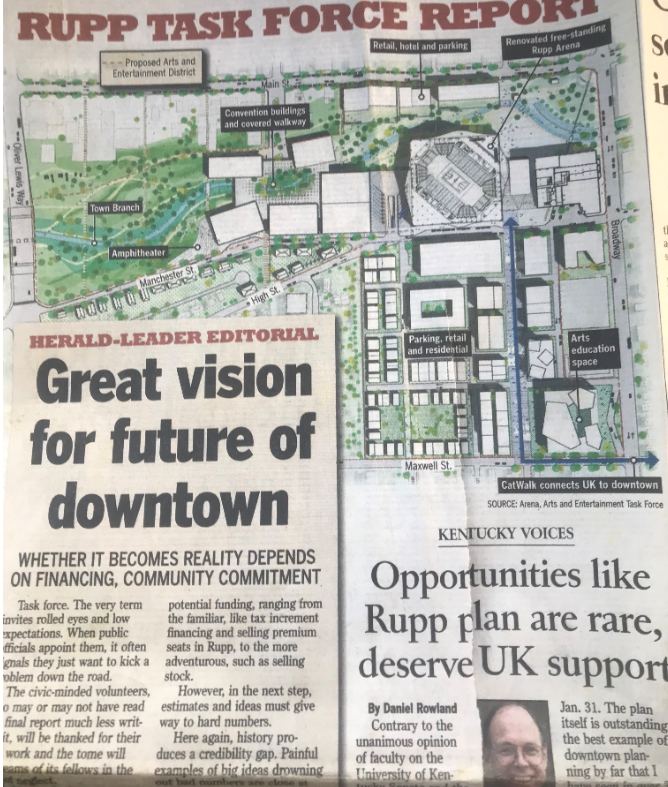

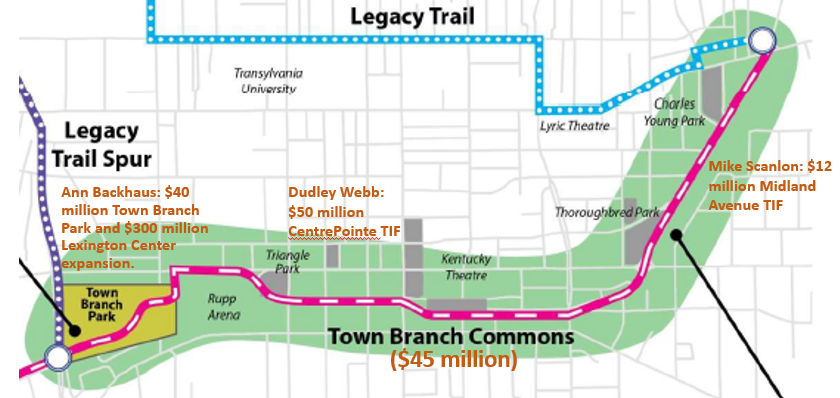

Over the next several months, many of these Lexington-first projects are set to come online: the Julietta Market, the MET, Rupp Arena, the Town Branch Commons, and the urban portion of the Legacy Trail. No doubt, the architects of these MALGA projects will be given ample space to promote their work as good, socially conscious community urbanism that captures the zeitgeist of the post-Covid city.

What follows is a critique of that triumphant MALGA story and a proposal for a different way to do Lexington urbanism. Keep these in mind as your MALGA leaders begin to get their media friends to goad you into trusting them to institute their next decade of urban projects.

Deserts and wells: Lexington-first design principals

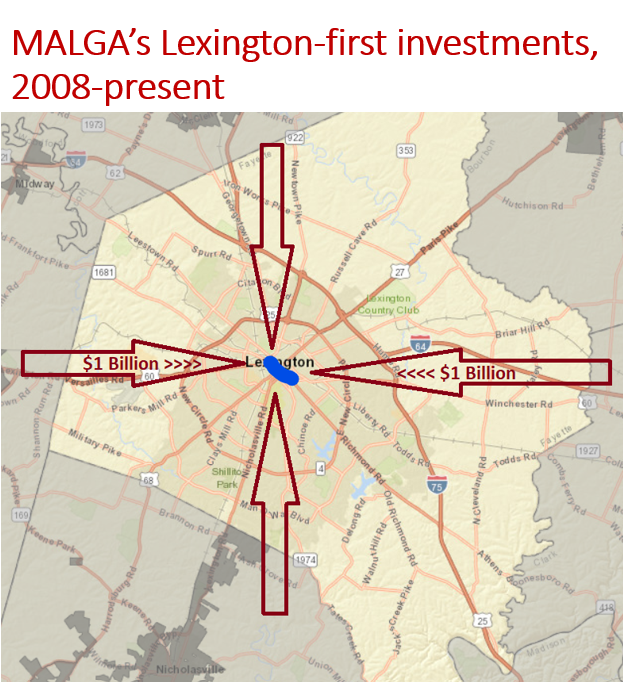

MALGA design principals operate on a Lexington-first model: an expensive, elitist focus on transforming our Main Street and its investable environs into a world class place that University of Kentucky students and professors can proudly recommend to their friends and colleagues living in hipper places.

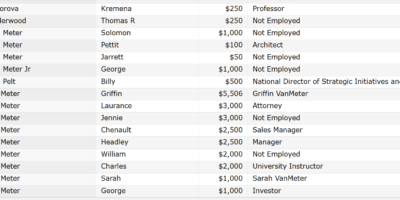

This Lexington-first design model was described in 2013 by MALGA leader and progressive architect Van Meter Pettit, the son of Lexington’s first Mayor of the merged government. Writing on why the city must invest $75 million into ripping up already-walkable downtown streets in order to construct a new “world class” bike/hike trail, Van Meter declared:

“Like a well in the desert, our downtown is so small and intimate that every option for maximizing its quality and economic potential is essential to pursue.”

This decade-long design ethic to use “every option for maximizing quality” in downtown Lexington has served both me and Van Meter well. But then again, we both live amidst the well that is downtown Lexington, in homes we own whose value increases by the day. Good for us.

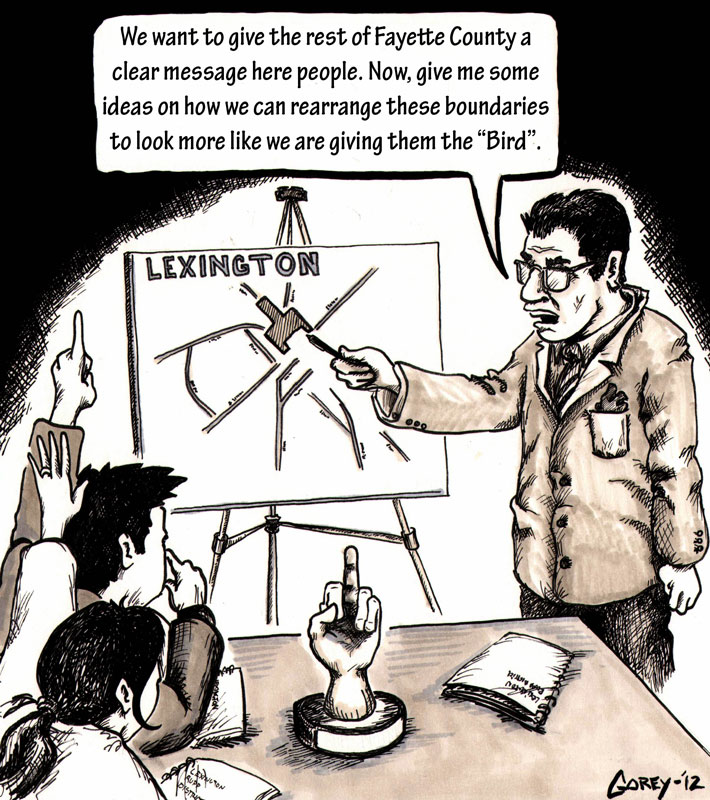

However, if you happen to live away from Main Street, in neighborhoods that Van Meter understands as the Fayette Urban County (FUC) desert, the Lexington-first design ethic has served you quite differently. Van Meter and other MALGA leaders do not state it outright, but what you, desert dweller, were supposed to get out of the decade-long, billion dollar project to build back better the greater Main Street area…was an ability to visit, tourist-like, the gushing Lexington well that Van Meter and I call home.

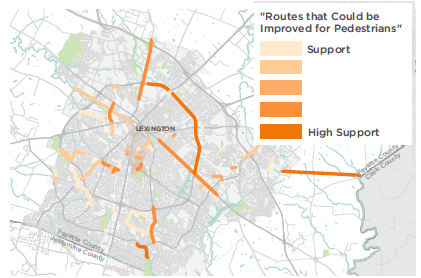

To access your arts, biking, food, business, music and other wants, MALGA design principals assume you will leave your aging neighborhood; pull your car (if you have one) onto clogged arterial roads with no sane bike lanes; cross giant intersections at Man O’War Boulevard and New Circle Road; park in refurbished and newly privatized parking garages; eat, drink, bike and be merry downtown; and then drive your car or SUV back home, intoxicated, to your parched desert neighborhood.

Now over a decade into the making, it should be clear that the MALGA design principals espoused by Van Meter were flawed. Let’s start with the painfully obvious: Lexington-first projects have taken years to complete, have cost an exorbitant amount of money, have mostly enriched this city’s uber-wealthy oligarchs and their patrons—and yet still seem to cover an uproariously little amount of city terrain.

Add up these basics, and its a billion dollars, over a decade of effort, and a few MacArthur geniuses to improve a single square mile of county land. Is that a design success? To MALGA supporters, it seems the answer is yes.

Added to these obvious (to most of us) failures, Lexington-first design principals have also proven to be socially retrograde. A decade of this MALGA work—a new Rupp, affordable housing for artists, bike trails along Main Street, city halls renovated for upscale dining and wedding events, and the like–has produced racial animosity and unrest in those gentrifying neighborhoods nearby Main Street. At the same time, the work has fueled a MAGA-like suburban animosity directed toward public and private leaders viewed (rightly) as decadent aesthetes uninterested in having anything to do with drive-by “desert” country—the places where most FUCers live.

A new design paradigm: FUC-Lexington

Clearly, what was needed over the past decade was not a city-first plan to benefit Van Meter and me, but rather a more diffuse county-first plan to cover a much greater territory and population. In other words, not Lexington-first (L-FUC), but Fayette-first (FUC-Lexington), a design vision that connects communities without bias toward promoting Main Street and all those Van Meters and Mayers and Pettits who own property around it.

Where MALGA design principals have focused on promoting the tourist brands of bourbon, horseys, craft beer, upscaled food and niche business incubators like KYforKY (run by a different MALGA-promoting Van Meter), FUC-Lexington prioritizes providing us—and not our friends jetting into horse-country—the freedom to move to and fro about town. It promotes Fayette’s many watersheds, imagines multiple Mains, values non-tourist businesses and builds infrastructure across diverse topographies.

FUC-Lexington urbanism will not be found in canned form on an Atlantic Cities blog; it requires of its practitioners a greater knowledge of (and affection for) the whole FUC than that which has been demonstrated by our sophisticated MALGA leaders.

A FUC-Lexington plan: Park Markets and Transit Sheds

The MALGA movement will surely soon pivot into a half-hearted embrace of their greater Fayette community. Lexington population growth trends, a need for new markets, and the awakening to a post-Covid world have already resulted in isolated discussions of Nicholasville Road (which, conveniently, runs alongside UK’s west flank).

But as with last decade’s focus on Main Street environs, beware of any newfound MALGA interest. Like a student showing up to take the final exam after skipping the entire semester of course material, a decade of MALGA leaders ditching out on any consideration of the off-brand county desert-lands is bound to produce (now that such consideration is deemed civically necessary) second-rate work.

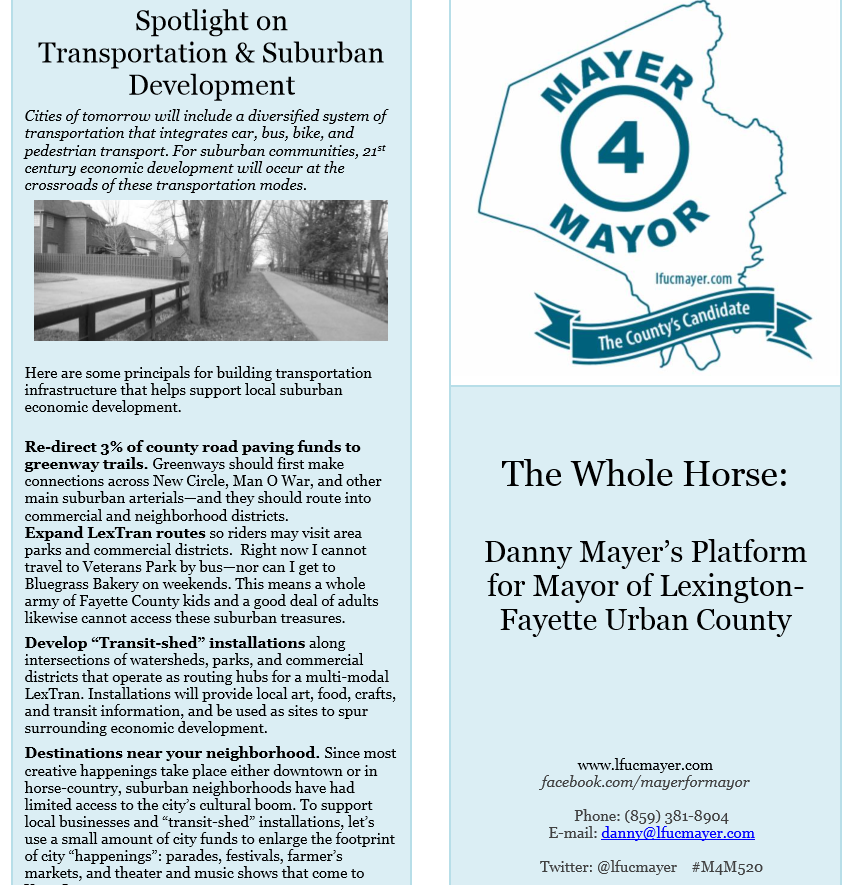

As luck would have it, though, there is a local FUCer who has spent over a decade considering an urbanism beyond Main: me. In newsprint, facebook posts and as part of LexTran youtube videos; through years of city hikes, council presentations and a 2014 run for Lexington mayor, I have developed a decidedly FUC-Lexington set of design principals.

(You may not be aware of my decade of work on this topic: gracious MALGA leaders with ties to the media, community and government are insistent that it does not exist or hold community value.)

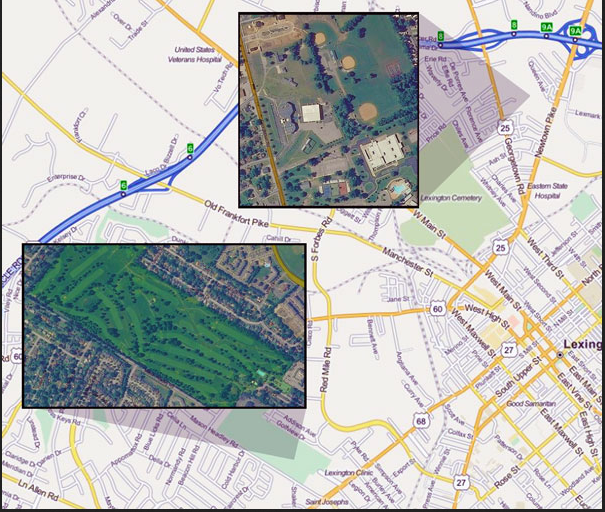

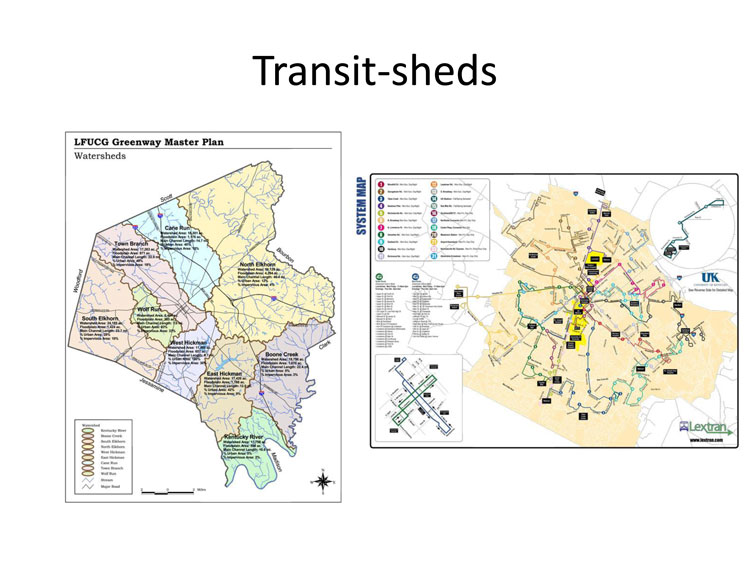

Over the coming months, I’ll spotlight some of this FUC-Lexington work. My own focus has been on threading bus-stops and bike paths across the city’s watersheds (Transit Sheds), and directing development into areas that connect our park system to the many already-established commercial districts that sit nearby them (Park Markets).

My FUC-Lexington design includes the Anniston Road and Oxford Circle commercial districts. It values the northern New Circle and south-eastern Man O’War corridors for who and what is there. It makes Douglas and River Hill Parks lynchpins for their communities. It takes us on walks across Wolf Run and the two Hickman Creeks, and provides both bus and bike access to them.

This county is big. It contains multitudes. Perhaps the biggest bummer of the MALGA movement, beyond casually bankrupting us in ways that have pitted local communities against each other to help a few well-known people secure a profit, is how absurdly small MALGA’s smug progressive urbanists made our city: a well in the desert.

It’s time we find a leadership and a design ethic that’s not afraid to wander in the desert. It’s time for FUC-Lexington.

5 Pingbacks