The New Old Fayette County Courthouse, part 2

In August 2014, the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Council received an update on the state of its former courthouse, a Richardson Romanesque structure built in 1898, renovated in the 1960s, mostly abandoned in 2001, and ultimately condemned in July 2012 for a variety of reasons, including high levels of asbestos, mold and guano. (Also, the roof leaked, and the heating and air conditioning no longer worked.)

Though this public icon stood at the center of downtown, adjacent to the city’s founding spring and original stockade, serving as the architectural anchor to its oldest and still most visible public square, the Old Courthouse had received little attention since its condemnation.

In the first five months after condemnation, in 2012, council took no action to fix or otherwise maintain the vacant building. Similarly, no resolutions or ordinances, no disbursement of funds, pertaining to either the maintenance or fate of the courthouse, appeared during the entirety of 2013.

Not until January 2014 did the condemned Old Courthouse, property of the people of Fayette County, return to public consideration, when City Council members voted unanimously to direct then-Mayor Jim Gray to apply for a $200,000 federal grant for environmental remediation at the site, and then again in May 2014, to seek a different $50,000 federal grant for remediation funds.

By the time of the August 2014 City Council meeting, neither of these grants had been awarded, and no actual remediation work had been performed on the structure. The Council update was most likely delivered in part by EOP Architects, who a month earlier had been awarded a $110,000 contract to assess the structural, architectural, and historic states of the building.

Unsurprisingly, the report to council documented the continued deterioration of the 1898 Richardson Romanesque building. Whereas the Old Courthouse had been condemned in 2012 as unsafe for human habitation, the 2014 EOP report to Council now declared the building unsafe for human approach.

Foundational supports in the basement had corroded to the point of structural instability; many of the building’s external balconies had begun to separate from their stone walls. To protect stray city walkers from death by falling rock, the city would need to fence off the perimeter.

Of this report, Council member Jennifer Scutchfield would observe:

If I have a hole in my roof at my house, I don’t spend 18 months to figure out how to fix it. [W]e are spinning our wheels on this. We’re gonna lose this building, if we’re not careful.

Scutchfield was wrong on some particulars. Four months later, in December 2014, the city would finally get around to shoring up the foundations and balconies (cost: $59,000), making it 29 months time for city leaders to figure out how to fix their leaky roof and crumbling foundation. Also, the building was not, in the end, lost.

But otherwise, the moment of civic honesty exposed an ugly truth about the city. Here was the city acting quite like a bottom-feeding capitalist: the civic slumlord with bat guano coming out its eaves.

City Surplus

In the larger story of how the New Old Courthouse came to be, the several year period between condemnation and renovation represents a sort of public black hole. At the time, the question of What to do with the publicly-held old Fayette County Courthouse registered a distant fifth on our city’s list of concerns, well behind the proposed public-private partnerships to renovate Rupp Arena and construct the 21C Hotel, and to build out the CentrePointe block and the Distillery District. The courthouse just wasn’t debated. Not publicly by civic leaders, not privately at the kitchen table. Consequently, the period has little in the archives to speak for it.

In official memory, the one written later by the victors, this marginally reported gray period has been buffed over, and in some cases, outright fabricated. Here is Lexington Herald Leader journalist Beth Musgrave describing these post-condemnation years to her readers in a 2018 article on the occasion of the re-opening of the renovated courthouse:

[After 2012], it sat empty for the next several years as the city–strapped for cash during the recession–debated what to do with one of the last remaining historic municipal buildings left in downtown.

Reading the journalist Musgrave, one imagines a gaggle of modern-day Henry Clays standing tall to offer their grand ideas over late nights at the capital building. The reality seems much more simpleminded: two years of absolutely nothing, then a month of Vice-Mayor Linda Gorton (now Mayor) asking, “Do we close it down and mothball it? Do we make it usable for just some basic kind of use, or do we tailor it for more specialized use?”

It is hard to characterize this slow pace as either deliberative or exhaustive. Let the record show that it took our leaders two years of deliberation to arrive at the same vague questions asked and answered in 2012 by Herald Leader journalist Tom Eblen. And, apparently, not a drop of discussion more than the Eblen Proposal. Farmer’s market space? Affordable housing? A publicly run kitchen on the order of DV8? There seems to have been little to no consideration of these and other uses for this building anchoring our oldest public square.

More disconcerting, though, is Musgrave’s re-writing of Lexington-Fayette Urban County history. The Herald Leader journalist states that the city put off renovation work because it was”strapped for cash during the recession.” This is an outright falsehood.

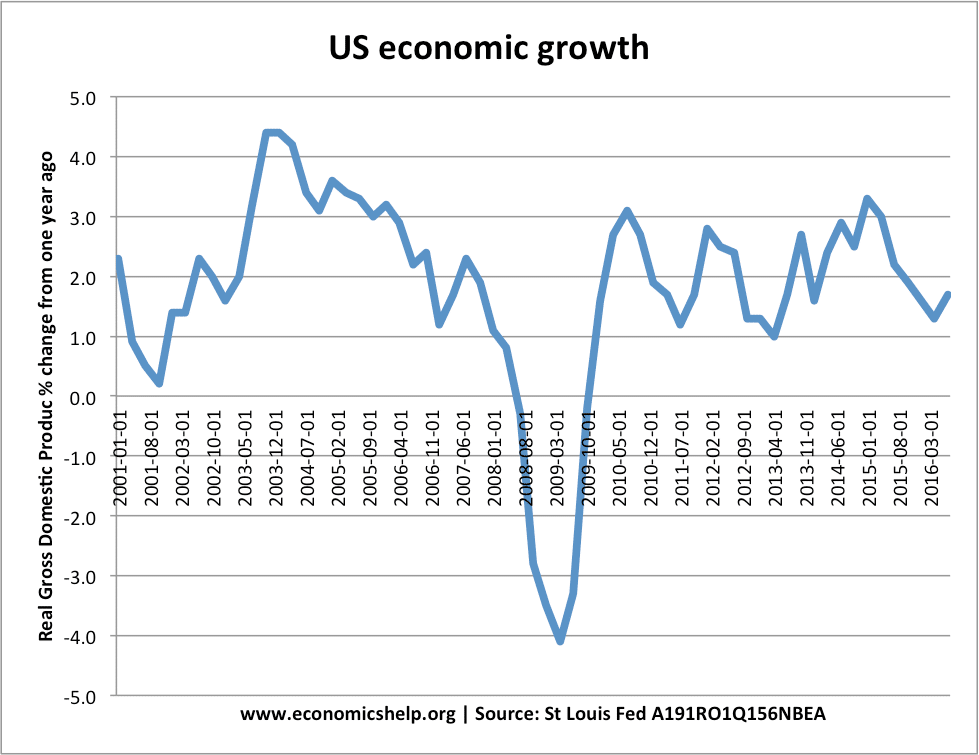

For starters, the Great Recession, to which Musgrave alludes, ended a full three years before the Courthouse was condemned. By 2012, when the stock market hit a new all-time high, there was quite the opposite of a recession: the country (or at least those urban areas anchored by large research institutions) was in full-on recovery during those years of delay when the courthouse roof was leaking and its foundations were wasting away.

Here in Lexington, 2012 marked the first of what would become at least three straight years of budget surplus. Musgrave herself penned an article on the first of these budgets, covering a Jim Gray request that “the council set aside $2 million of a $12.5 million [budget] surplus for an economic development fund called a Jobs Fund.” The city was hardly “strapped for cash” during the years that the courthouse sat vacant. It was just that none of the city surplus went to shore up the vacant and condemned courthouse.

Mostly, this surplus was spent on other city priorities. In 2013 alone, city leaders voted to direct $2.5 million of general fund monies to study how to renovate Rupp Arena, and then, to help pay for that study, got the state to tap the Coal Severance fund for another $2.5 million. It entered into a $50 million TIF agreement with CentrePointe Parking Garage LLC. It secured $22 million in local, state, and federal subsidies for the 21C Hotel renovation.

Civic Slumlordism

In urbanist circles, slumlords inhabit the very bottom of what the geographer Neil Smith called “the rent gap,” or the difference between what a property currently makes in rent versus its potential rental value. Slumlords, Smith argued, generally do not invest in their decaying properties because they can not expect to see future returns on their investment. Only when a property’s potential value increases—when the neighborhood changes, say, and wealthier tenants can be expected to arrive—will a slumlord re-invest (or, as is often the case, sell out to a new owner).

In Smith’s formulation, it is the disinvestment bottoming out that helps spur the re-investment. The ultra low costs of purchasing dilapidated and condemned homes make most future investments profitable, which is why much early gentrification takes the form of renovating “empty” and abandoned housing stock.

Of course, we all know to what kind of tenants the slumlords rent: the poor, the marginalized, the on-the-dole, the disempowered, the migratory, and those with nowhere else to turn. And we are starting to recognize the typology of those first-wave gentrifiers who tend to succeed the slumlords: artsy, amenity-focused, food-forward libation drinkers in search of endless authentic parties.

In the case of our Civic Slumlords, we might take note of the Courthouse tenants from 2010 who were forced to leave when their air conditioning and heating went out, the roof continued to leak, and the mold and guano became unbearable (though not yet condemn-able). In our old Courthouse, these marginal tenants were a group of disparate local history museums, none of whom, since eviction, have found a permanent Lexington home.

In our newly renovated Courthouse–$32 million dollars newly renovated–the new tenants represent the craft food and beverage industry, the city’s tourism industry, the region’s horse industry, and a top floor party space.

Billie Mallory

Now we are looking at same situation with the city hall building, old Phoenix Hotel, that has been discussed publicly for at least 4-5 years, while it continues to crumble, literally as the facade pulls away from the rest of the structure but only ‘bandaid’ relief has been applied until it is no longer structurally sound.

Sound familiar? That’s how gentrification takes place, the talking heads discuss, study and have task forces to analyze the issue, while neighborhoods literally fall apart around them. They discount what residents report, as many either die in place or move out when given the chance. Houses and storefronts sit vacant for years, get bought up by speculative investors and sit empty for more years, while some redevelopment begins at the edges and we call it urban renewal. But many of the original residents have left in apathy or they turn on each other with crime to grab a few crumbs of what is left.

A few new policies are proposed that are about 10 years too late to make any difference for those neighborhoods that are most vulnerable and least able to help themselves. Much of the history has been buried deep and cultural fabric forgotten, while our elected leaders ride up in their white city cars to save the ‘hood but it’s already gone. Too little, too late-while they ask for our votes again to ‘finish what they started’.