Part 2 of “BREAKING: Brooklyn genius Kate Orff adopts key part of NoC’s 2013 #FreeLexTran proposal for the Town Branch Commons”

One of the curiously under-mentioned aspects of the soon-to-be-completed Town Branch Commons is how the trail mostly side-steps any of the city’s actual needs for better pedestrian and bike-connectivity. It costs a very lot and provides only a very little.

I had hoped to compose a follow-up to a story I began earlier last month, which focused on how North of Center hatched the 2013 idea—now validated by city leaders and the world class Brooklyn design firm SCAPE, home of Macarthur genius Kate Orff—to save Lexington’s MLK Viaduct from its planned demolition to make way for the Town Branch Commons.

But I’ve found that I can’t tell that story without getting at how the Commons, at least since the Rupp Arena Task Force had Master Planner Gary Bates re-introduce the concept in 2011, has always missed the mark as a high-priority signature city project. This aspect of the nearly 10-year old project has been seriously under-reported, which has had the intended effect of poisoning community awareness and discussion about it.

In many ways, the Commons are a great example of what the transit planner Jarret Walker cites as elite projection: “the belief, among relatively fortunate and influential people, that what those people find convenient or attractive is good for the society as a whole.” Here’s MALGA thought-leader Van Meter Pettit projecting his elitism onto the need for a $75 million city Commons to accompany the $350 million Rupp Arena renovation:

Like a well in the desert, our downtown is so small and intimate that every option for maximizing its quality and economic potential is essential to pursue.

Jarrett, a guy who has spent most of his adult life trying to get elite civic, business and other leaders like the Pettit family to re-imagine their city’s decrepit bus systems, does not mince words: “Once you learn to recognize this simple mistake” of elite projection, he writes, “you see it everywhere. It is perhaps the single most comprehensive barrier to prosperous, just, and liberating cities.”

NoC’s 2013 plan to save the MLK viaduct was rooted in highlighting and ameliorating some of the elite projections like Pettit’s that were getting baked into the Commons project. Since writers and other leaders in this community have failed to address any of these Town Branch issues publicly, I thought it best to address them head-on in a separate post. I will focus on three moments of elite projection that have negatively shaped our Commons infrastructure.

Elite Projection 1: Poor Project Placement

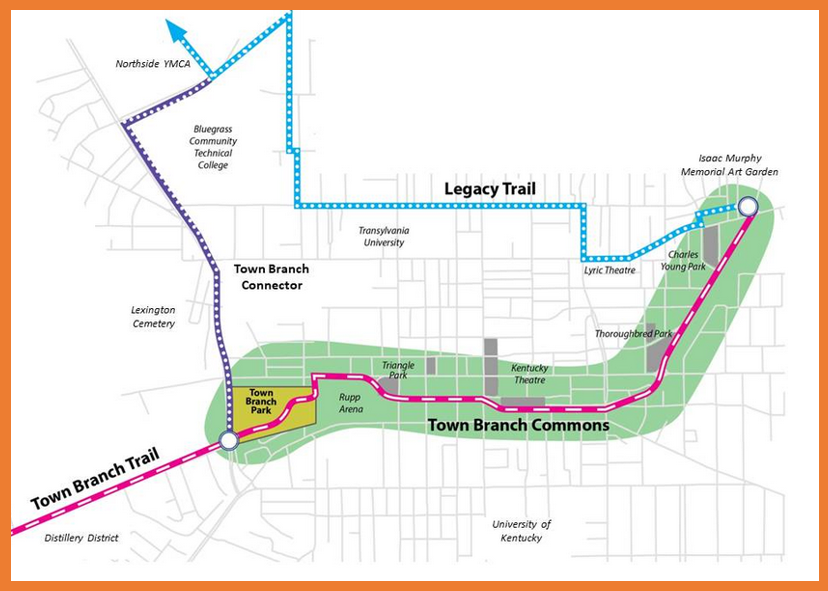

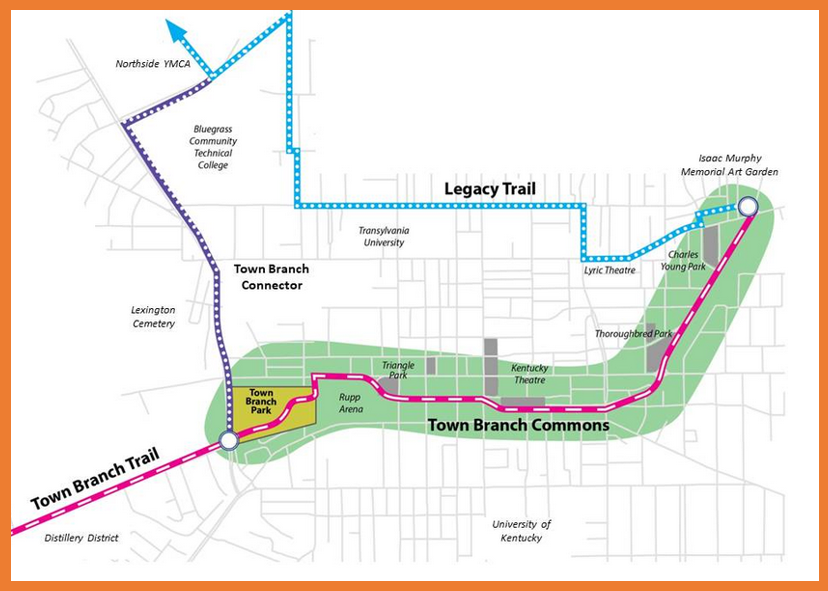

The Town Branch Commons is a high-cost solution in search of a grand problem, and this isn’t really up for debate: the entirety of the $75 million, 2.2 mile trail sits within a half mile of last decade’s signature trail project, the Legacy Trail, whose portion running parallel to the Commons cost under $2 million to complete. At this rate, we’ll get community bikeways across the rest of the city by sometime in the year 2338, and at a cost that should reach into the trillions.

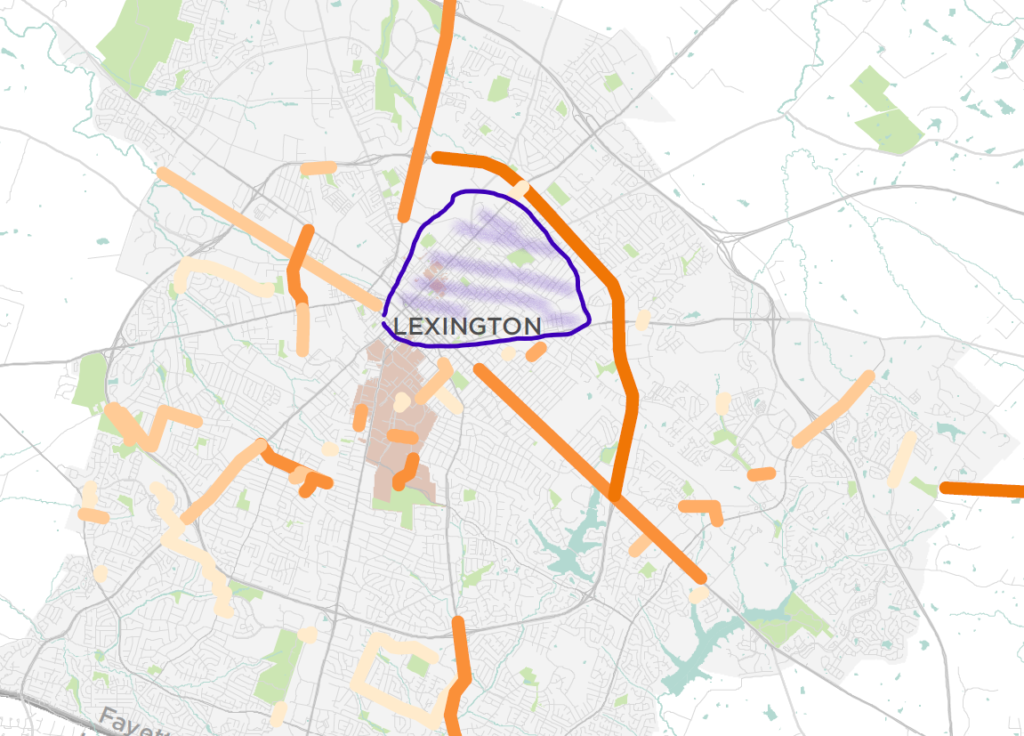

But there is a larger managerial and community ignorance at play here. The choice by local leaders to focus their bike-hike efforts on Vine and Midland over-rode the city’s own data and community expertise. For years, this input showed that downtown, while not perfect, was also not specifically a problem area for Lexington walkers or bikers.

When it comes to the city’s pedestrian and biking infrastructure, the far greater documented needs (then as now) lie outside the downtown core. Crossing New Circle or Man O’War. Cycling along Richmond or Nicholasville Roads, or upon Tates Creek or Old Paris Pikes. Connections into commercial spaces like the mall, Lexington Green, Oxford Circle, the North Circle strip malls, or the like.

In choosing downtown, city leaders simply made the wrong choice, and this choice was not value-free. On the one hand, their choice certainly enriched their world. Leaders like Pettit and Lexington Herald Leader journalist Tom Eblen chose to throw their considerable weight behind building a kickass trail that just so happened to pass within 300 yards of many of their Bell Court and Mentelle Park homes…and that then dead-ended at a place where most held coveted and expensive season tickets to UK Basketball.

On the other hand, the ramp-up and 2015 approval of the Town Branch Commons trail coincided with a relative halt in the development of bike-hike trails that were placed in other parts of the city—those places city data have long said are in need of upgrades, and where many of our MALGA leaders will never visit. This elite managerial choice to green-light the Commons has set back the rest of this city’s biking needs by at least a decade.

It was a classic case of being strategically half-right. Seizing upon legitimate city-wide concern for greater bike and ped connectivity, our local elites went pufferfishing to their neighbors on the need for a world class Town Branch Commons, something really nice to show off to their fellow elite facebook friends in Louisville or Brooklyn or Austin.

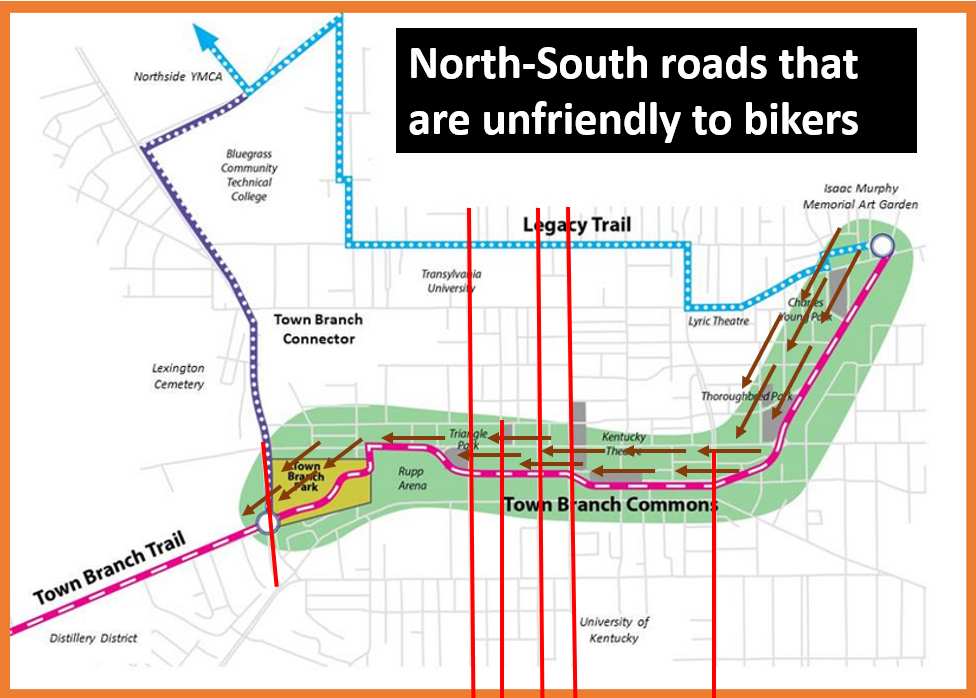

Elite Projection 2: East-West solutions for North-South problems

But the Commons have been doubly poorly placed. True, the Commons do mis-direct LFUCG’s scarce alternative transportation resources into constructing yet another expensive downtown project, but our elite designers who set the conditions for the trail also seem to have completely misunderstood the existing impediments to walking and biking in and through downtown Lexington.

This second mistake is a design error that resides at a more nitty-gritty downtown-level, and one that should strike directly at the claims in this city of managerial and design expertise. The project expends a lot of energy and money to provide comically little new infrastructure for getting people to and through downtown. As a result, the real issues downtown does have with bike-and-ped connectivity are neither fixed nor even addressed by the Town Branch Commons.

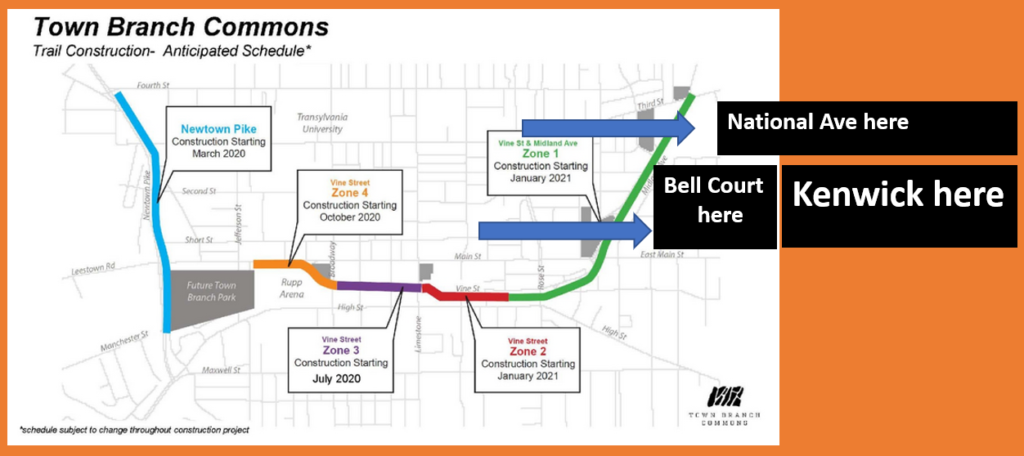

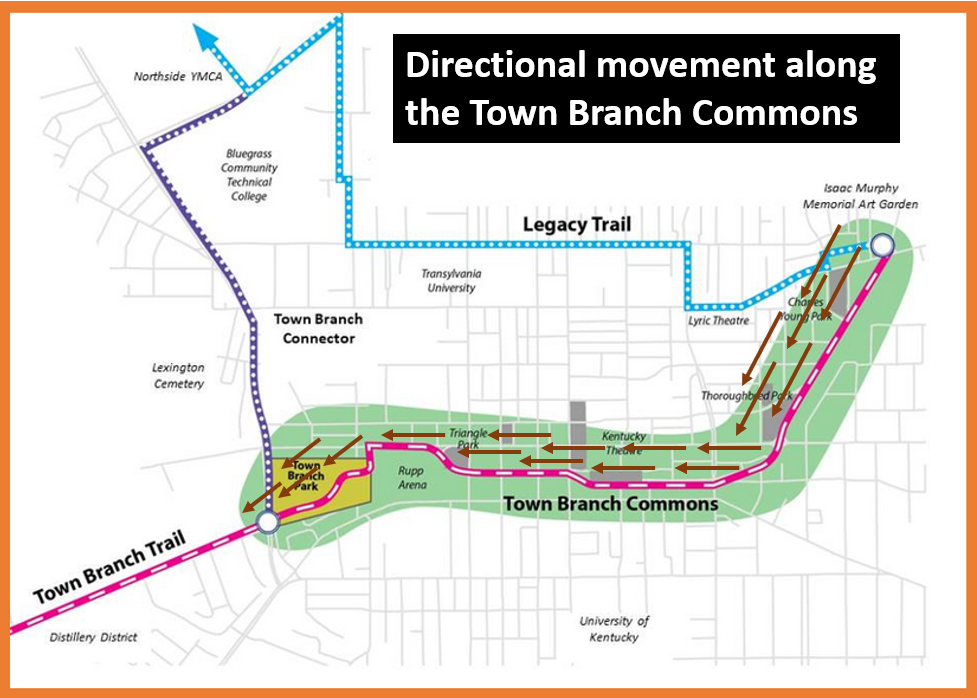

Take a closer look at the trajectory of the Commons, which appears as a fallen hockey-stick that runs south-west along Midland and then cuts West along Vine Street.

We might intuit from this trajectory that our Bell Court leaders clearly felt downtown’s connectivity problem was that walkers and bikers in the East End experienced infrastructure impediments that limited their southwest movement toward Main Street. And that people moving East-West though the urban core have been similarly hindered.

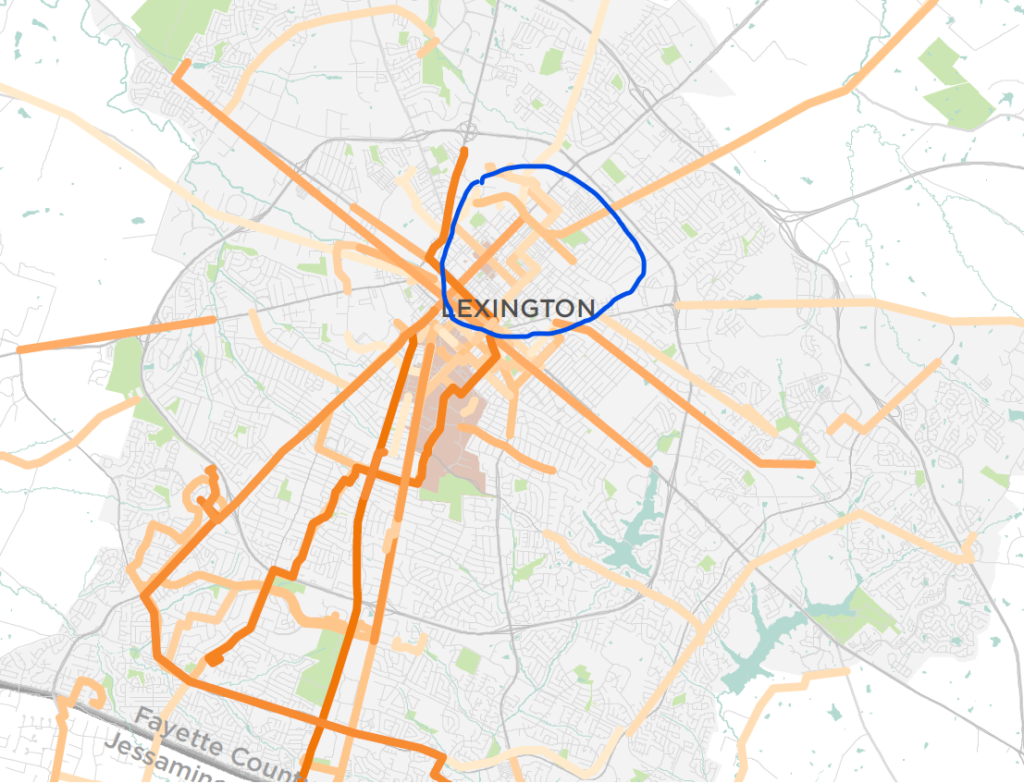

To put it mildly, these assumptions—which seem to have guided the Commons Trail along every step of its 15-year evolution—are hogwash. Ask anyone living near downtown Lexington: East-West movement parallel to Main Street throughout our long-and-narrow downtown core is already an easy proposition for bikers, hikers, joggers, and walkers. Between Vine Street and Loudon Avenue, any number of nearby streets perform that work already, including Short, Second, Fourth and Fifth Streets (and, with bollards, even Main Street). One of these streets, Fourth, is where the just-completed Legacy Trail runs, for Fayette Urban County’s sake!

To be sure, none of these are perfect options. But against the rest of the city’s alternative connection needs, movement along what will become the Town Branch Commons has rarely been an issue for people downtown.

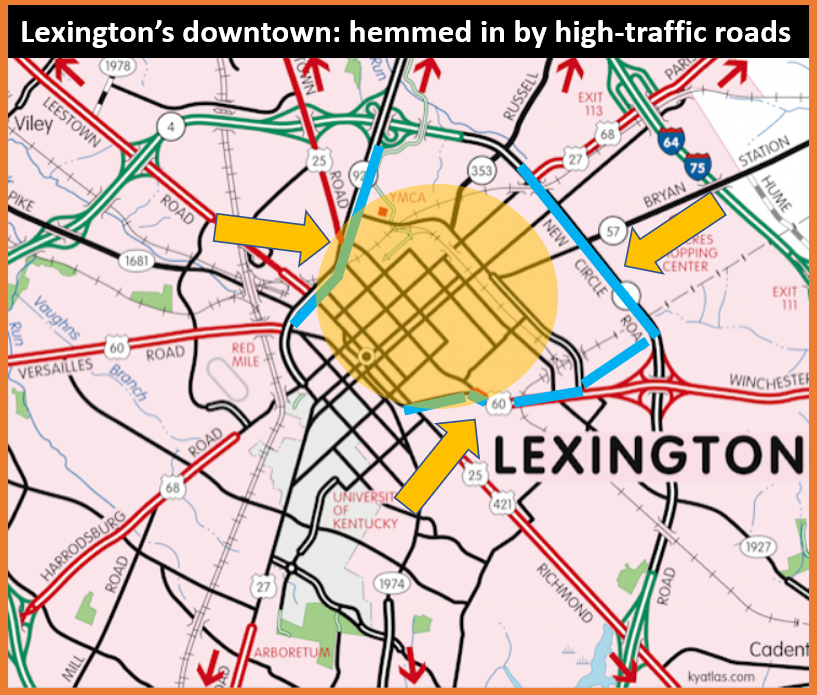

To the degree that downtown does have hike-bike issues, these tend to mirror the problems non-elite residents have been citing for years about the challenges of navigating their own off-brand neighborhoods: (1) having to compete with car traffic along high-traffic arterial roads, and (2) difficult crossings of such high-traffic roads that separate neighborhoods from commercial districts like the Ohio River that separates Cincinnati and Covington.

In our horizontally-oriented downtown, these challenges converge in the seven or eight blocks between Main Street and the University of Kentucky to its south. (You can see this issue on the bike-needs map included earlier.) In this area, north-south roadways Rose, Limestone, Upper, Broadway, and Newtown Pike are dominated by cars and unfriendly to bikers. The lack of a safe and efficient north-south bikeway through this area limits the amount of connections that UK’s 40,000 students, staff and faculty have with the commercial districts and residential neighborhoods located to the north of Main Street.

This is downtown’s biggest hike-bike “connectivity” issue. And yet, in our second example of Lexington leaders being strategically half-right, the Lexington Downtown Development Authority tried to fix downtown Lexington’s North-South bike problems by soliciting international proposals…for a glamourous East-West fix.

Elite Projection 3: No Midland Crossings

The second very common city-wide complaint that elite projection failed to address with its Town Branch Commons project is better infrastructure for crossing high-traffic areas. In downtown, the lack of such crossings transform downtown into a sort of transit peninsula, with Winchester/Midland to the East, New Circle on the North, and Newtown Pike to the West hewing the urban core from surrounding neighborhoods. Much like last decade’s signature project, the Legacy Trail, the Town Branch Commons makes no attempt at providing infrastructure for crossing the high-traffic street that runs alongside it.

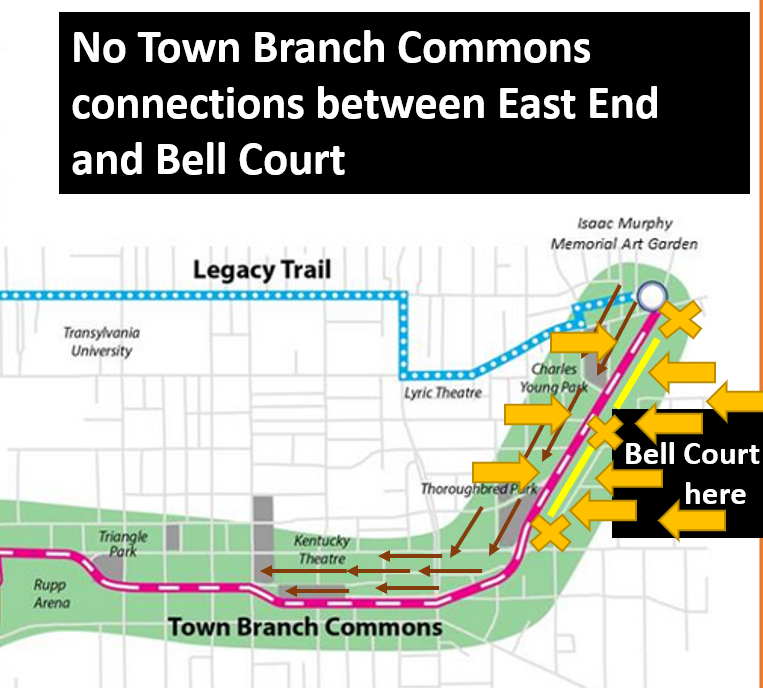

Despite running for nearly a mile along Midland Avenue, despite having the ability to connect the historically black East End to Bell Court for the first time ever, despite at least three logical places for crossings into a lot that is now property of the Fayette County Public Schools, despite at least one recent biking death along that corridor from a man trying to cross at one of those logical places….the Town Branch Commons appear to have planned for zero (0) crossings of Midland.

This one is a head-scratcher, since much of the elite projection resides in Bell Court and sprawls eastward into the relatively dense inner suburban neighborhoods of Mentelle Park, National Avenue, Kenwick, and Queensway. Why did they design such grand shit, and then not give themselves an improved way to access it? In terms of the project, a couple improved street crossings was layup urbanism.

I imagine that part of it has to do with lingering Bell Court classist racism, which has long attempted to uphold the Midland divide between itself and the poor black East End. When Town Branch Commons was on the design board—when the elites were making the missteps relayed above—the East End had not yet gentrified, and #woke rhetoric had yet to hit the city in any profitable way. As designed, the Town Branch Commons were….close enough for Bell Court. Bell Courtesans could access it, but it remained difficult for the rest of us to access them.

Whether this is good enough for Kenwickers and the less-elite elite living in those neighborhoods beyond Bell Court remains to be seen. I imagine National Avenue businesses would love to have a bike route to connect NoLians without having to take a brief ride on Midland and Winchester. I could see some Mentelle Parkers who might rather not have to bike on Richmond Road to access downtown ultimately wishing that the Commons had simply made a crossing at Second Street that would allow them to route through Bell Court instead.

Jarrett, the transportation designer who coined the phrase “elite projection, has a related though I think more broad reaching explanation.

“The mistake that elites are constantly at risk of making” Jarrett observes, “is to forget that elites are always a minority, and that planning a city or transport network around the preferences of a minority routinely yields an outcome that doesn’t work for the majority. Even the elite minority won’t like the result in the end.”

And when the elite minority inevitably revolts, you let them know that you heard it here first.

Yong Guan

“The lack of a safe and efficient north-south bikeway through this area limits the amount of connections that UK’s 40,000 students, staff and faculty have with the commercial districts and residential neighborhoods located to the north of Main Street. This is downtown’s biggest hike-bike “connectivity” issue….”

100% correct. I live in Southland, and to get to UK and downtown, it involves cutting through Hunter Presbyterian Church parking lot, Central Baptist Emergency Room parking lot, Shawneetown Apartments, then University Drive to the main library. From UK to downtown, though, is trickier — bike lanes start on Limestone just past Administration Drive, which means cutting through campus on sidewalks or Rose Street to Euclid.

East-west in downtown is easy — if traffic isn’t bad, Short Street to Elm is beautiful and fun; 4th St. with green lanes is great if they’ve been recently swept free of shattered glass (on W. 4th, a billion pieces of crushed limestone is the tire killer of choice). But east-west has lots of great options, north-south has zero.

I’ve no clue if Lex. has a comprehensive, long-term plan for bike lanes. Long ago there was a bike commission. I went to one meeting only to find out that head of the agency/commission, which was a paid position, not only did not commute via bike to work but didn’t even OWN a bike. That told me all that I needed to know. I never went back.

That’s my .02

Danny Mayer

That can’t be, Yong! UK’s the 2018 Most Bicycle Friendly College in America. Your bottleneck from south-to-north cannot exist anywhere near there.

https://uknow.uky.edu/campus-news/uk-named-most-bicycle-friendly-college-america

They’re Gold level. You must be mistaken.

Have you tried University>>angle toward Rose>>New Student Center>>>MLK into 4th/5th?

Yong Guan

Three quick points. First, the “5 E’s” of the Bicycling Mag.’s criteria for a “Gold Award” notwithstanding, my criteria is more direct — can I ride from south Lex. to north Lex. and in/around UK safely, and, well, it’s just not an easy thing to do.

I haven’t tried the route you mentioned but I will this morning, and I’ll think about Zhang YiTang while doing so…

Best point for all who read this to remember — Zhang YiTang, one of the world’s greatest living mathematicians (solver of the twin primes conjecture, winner of the Ostrowski Prize and the MacArthur prize, to name but a few honors), now a full professor at UC Santa Barbara, once worked at the Subway shop on East Main and MLK. Read or watch a documentary about him (“Counting from Infinity”)

Billie Mallory

You can’t be remiss in mentioning how the developers planned to displace one of our oldest black churches, Main St Baptist by butting up to the back with parking garage and creating main entry into park to the side that eliminates most of their parking and right of way between their 2 properties. The public discussion has been disgusting, offering little compromise and finally an ultimatum to ‘take it or leave it’. Lexington only cares about its history as long as it does not get in the way of progress if something that is bright and shiny (pieces of silver). Downtown is really a painful reminder to many minorities of how Lexington was built on the backs of slaves and poor laborers. I don’t know too many black/brown or poor folk who desire to go downtown to a large park; they much prefer having a nice, safe park in their own neighborhood. Lest we forget, we just continue repeating that history.