Last month, I wrote a piece, “The Rise of the Story Catchers,” that detailed some of the non-profits who made money and secured city power off organizing and presenting the collective voice of the northside Hood, a voice that always (natch!) seemed to conform to the needs of new businesses locating there, with whom said story-catchers were often quite intimate.

The article was part of a larger set of stories that look at how the Hood, specifically the greater northside community that I have gentrified, has been repeatedly mined for value by outside speculators in ways that mirror how Appalachian communities were mined for timber, iron, coal, ginseng, voting blocks, culture and the like.

Story-catchers, individuals and groups who derive much of their value from the perceived position they hold as community-based activists, entrepreneurs or artists, play an important role in defining community needs and wants: what you might call the boundary of the acceptable, or as it were in Lexington, the fashionable.

Enter CivicLex

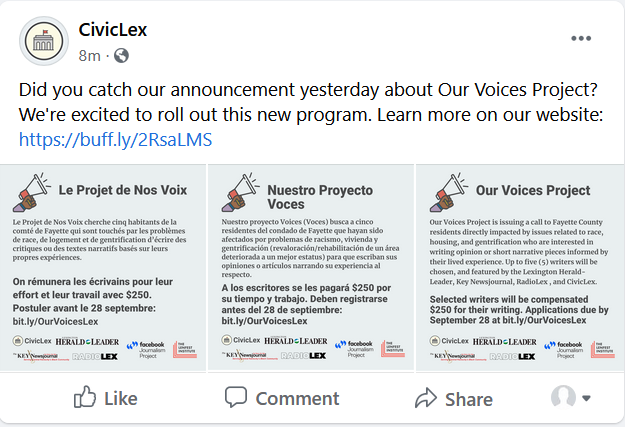

Now, as if on cue, the nonprofit CivicLex, whose mission is to “bring daylight to the issues, policies, and procedures impacting Fayette County,” formally announced last week its intent to go out and story catch some authentic Hood voice.

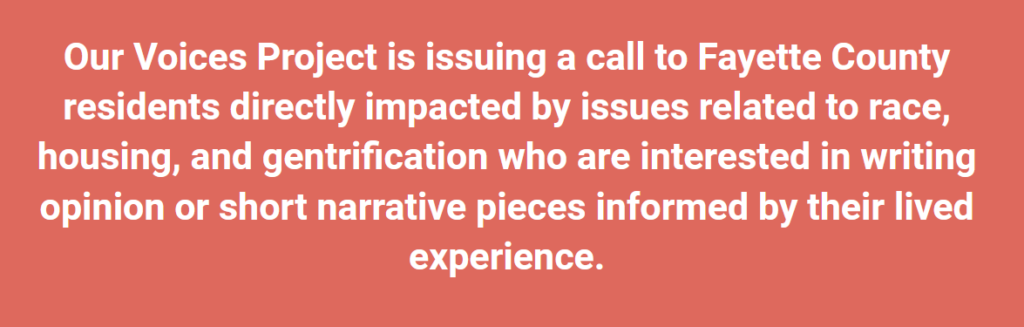

The non-profit intends to shed some light on Lexington gentrification, and it will do this through an $18,000 Facebook Journalism grant and a partnership with the Lexington Herald Leader that solicits “Fayette County residents directly impacted by issues related to race, housing, and gentrification who are interested in writing opinion or short narrative pieces informed by their lived experience.” CivicLex will select up to five worthy residents, help them craft their stories, and pay them $250 for the stories to appear in the Lexington Herald Leader.

This news should strike you as both laugh-out-loud funny and Eastern State Hospital crazy.

CivicLex has zero experience producing journalism. At its best, the nonprofit operates as a platform for disseminating LFUCG documents–a civic data circulator for the social media age. Useful as far as it goes, but hardly community journalism.

Even granting CivicLex its journalist status, the non-profit is still uniquely unsuited to produce anything at all about gentrification beyond a whole bunch of apology letters. Both the nonprofit and its founder, Richard Young, have a long history both producing and providing cover for a decade of northside Lexington gentrification. For the group to now get paid by Facebook to solicit and curate gentrification narratives is sort of like a Massey Coal-funded nonprofit using Koch Industries grant money to produce global warming testimonials for the residents of Pikeville to read in their local paper.

Where, to take a relevant example, did the publicity-forward, media-driven, northside-based CivicLex stand on the subject of gentrification, race and housing before a white Minnesota cop suffocated a black man in front of a crowd of horrified spectators wielding I-Phones?

It didn’t. The daylight-bringing nonprofit mostly sat out the gentrification debates in Lexington. A closer look at its record shows that it instead worked with other community members to downplay the important city issue. How else to explain why the word gentrification does not merit a single mention on CivicLex’s “City Issues” page, which the community organization has been building out since its inception in 2017. (The page currently lists 15 issues.)

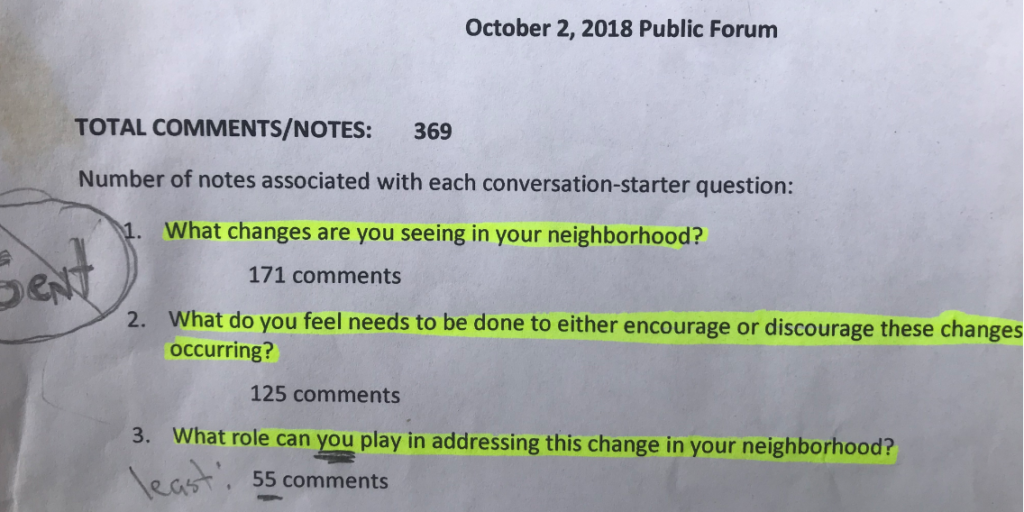

Or that, when offered the ability to speak during the two pre-George Floyd years in which the city’s Neighborhoods in Transition (Gentrification) Task Force met, CivicLex members refrained from public comment. Or that it never produced, as it has done for other issues, a report on these gentrification-focused meetings to circulate on its social media platforms. Or that it also failed to amplify those community voices that did take the time, pre-Floyd, to report on the way civic leaders were addressing the city’s race and gentrification issues.

Which is not to say CivicLex has been wholly absent from the civic conversation about gentrification.

The day-light civic group had behind-the-scenes, off-record, access to the NiT(G) Task Force’s co-chairs, District One Council Member James Brown (a gentrification agnostic) and the Vice Mayor Steve Kay (a gentrification denier), working closely with the two city officials to structure how the Task Force would interact at its first forum with a (largely black) public audience.

You may be able to guess what key-word CivicLex helped our councilmembers to eliminate from community conversation.

Add these silences together and it’s hard to see how, pre-global protests about that black man and woman getting killed by Minnesota and Louisville police, CivicLex demonstrated any interest whatsoever in making Lexington gentrification an issue for its polity to consume.

Why was that?

CivicLex is ProgressLex

Expand the frame to the past ten years, and CivicLex’s hidden role in city gentrification deepens. This is in part because the CivicLex of 2020, now snagging Facebook money to adjudicate a public conversation about gentrification, is the re-branded and re-named nonprofit formerly known as ProgressLex.

That nonprofit, like its re-named successor, also self-identified as a journalism of sorts. As a group of community bloggers, ProgressLex tirelessly promoted the cultural and economic appropriation of Lexington’s northside (its gentrification) as an uplifting, authentic, progressive and community-led neighborhood revitalization. The non-profit’s tag-line: We love Lexington.

ProgressLex was founded in 2009 by Ben Self, who would go on to found Lexington’s first craft brewery, West Sixth, and eventually serve as the state chair of the Kentucky Democrat Party, a position Self continues to hold. In 2009, Self had just moved back to Lexington after selling his lucrative stake in Blue State Digital, the online campaign outfit that had recently powered the Democrat Barack Obama to the presidency. ProgressLex was Self’s first entrepreneurial Lexington project, and it got the immediate reception that Self’s Obama-adjacent stature demanded.

In much the same way as a Massey-funded think tank might operate, ProgressLex provided a platform for serious-sounding Lexingtonians to foreground their urban professional class interests (and also personal brand) as city-wide needs. The news outlet did feature urban non-profit managers showcasing how much their organizations helped the community, but mainly it was a mouthpiece for the sort of development preferred by fellow Democrat Jim Gray, then Mayor of Lexington.

ProgressLex advocated expensive downtown investments that leveraged the city’s brand (horses, bourbon, basketball, UK), historic preservation, good urban design, and local entrepreneurs who were gentrifying the northside.

All this was progressive boosterism at its Obama-era peak, and in hindsight, it’s become clear that ProgressLex priorities added fuel to the gentrification of the northside (and also to the impoverishment of a surprising number of suburban locations, but that’s a story for a different time). Take a look at the people and businesses that are commonly understood as agents of northside gentrification, and there’s a good chance they were promoted a decade earlier as community talents by Ben Self and the ProgressLex Board.

Thankfully, ProgressLex went dark as a media outlet in 2015, about the time it was becoming difficult to deny that the things it had advocated for were producing societal unrest in the form of massive inequality, crumbling infrastructure, urban gentrification, suburbanizing poverty, and high city debt.

ProgressLex is CivicLex is NoLi CDC

ProgressLex may have been left to die quietly, but in 2017 trained cellist Richard Young purchased the ProgressLex name and re-branded it as CivicLex.

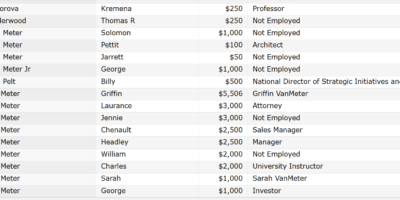

In a ‘you-can’t-make-this-gentrification-shit-up’ backstory, Young previously worked for NoLi CDC, a Lexington non-profit community development corporation founded by major northside for-profit developer Griffin Van Meter, the horse-farm connected dilettante whose vast Hood holdings provided him the un-ironic name ‘Ambassador of North Limestone.’

NoLi’s presence in the community is and has always been a source of great contention because of its tireless work promoting an artist-led gentrification. In one of Young’s first acts with NoLi CDC, the cellist won a $400,000 ArtsPlace America grant that, along with some of the first disbursements of the city’s affordable housing trust fund, allowed he and Van Meter (along with a VanMeter in-law, Kris Nonn) to purchase, renovate and sell an entire block of low-income homes to a population of imported artists and makers.

Despite winning the lucrative grant and a good chunk of the city’s first, underfunded, allotment of affordable housing funds, the three self-styled community activists professed no knowledge of affordable housing, nor of the low-income community in which they were creating their affordable housing.

In a synergy that NoLi openly promoted, the intent was for these new subsidized residents to further contribute to the area’s business-led revitalization, most of which was taking places in buildings owned by the neighborhood’s three main gentrifying landowners, Van Meter one among them.

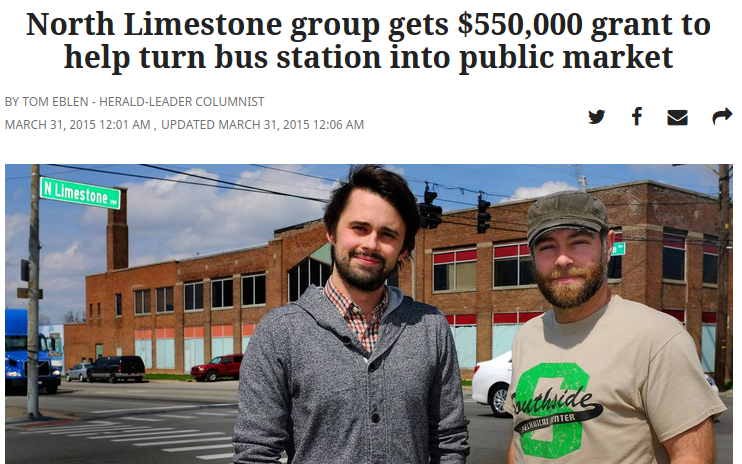

(NoLi CDC has since partnered with the second chief landowner, Chad Needham, on a $5 million renovation of the former LexTran public bus headquarters, which Van Meter and third-chief-landowner Marty Clifford had shut down in 2013 by getting the building put on the National Register of Historic places.)

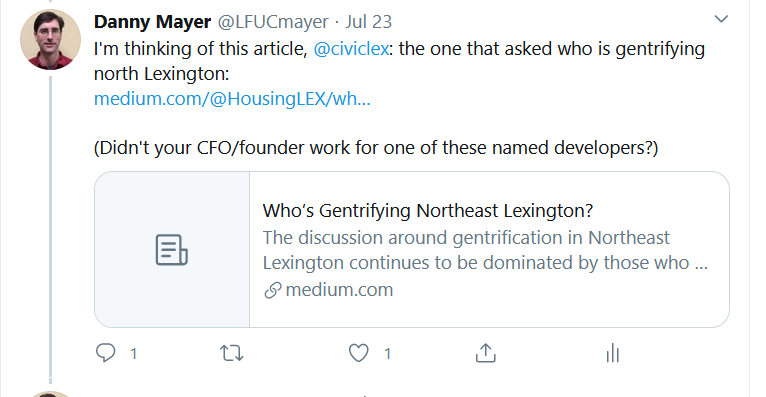

Since re-branding ProgressLex as CivicLex in 2017, Young continues to be strategically ignorant about the topic of gentrification. As recently as June, the head of the daylight nonprofic CivicLex was openly casting shade on the gentrification-based lawsuit brought by the family of Breonna Taylor against Louisville city government.

History doesn’t matter if you can get paid grant money to re-brand

And yet, amazingly, despite this regressive civic history, it is Young’s current nonprofit that will be getting paid by Facebook to act as a community journalist. As community journalist, it will select which gentrification voices are granted access to tens of thousands of Herald Leader readers.

Young’s nonprofit, in other words, will be using Facebook money to take control of a decade old debate on city gentrification that he has spent his entire professional Lexington life evading or dismissing as misdirected and anti-community claptrap.

In essence, Young and Civic/NoLi/ProgressLex have benefited from both ends of the gentrification debate: on the front end, they made money and secured power through grants that embedded gentrification policies into the northside fabric. On the back end, meanwhile, post-Floyd they are making money and securing power by soliciting and curating the voice of Hood residents–or at least the ones not likely to question last decade’s actors and their immediate relationship to the problems CivicLex now wants to face (post-Floyd).

Good for Young, I suppose, and good for his media non-profit’s continued success. $17K is not small change; the amount is about $16,500 more than North of Center’s entire annual budget. Neither is the $250 CivicLex will pay its Hood contributors. I know I’ll be reading them. I can already envision who some of those select writers will be.

But still, you gotta wonder whether CivicLex’s late and uninformed entry into the gentrification game will benefit the city or impact its residents who have been getting displaced all these years. My bet is on all this doing more harm than good. Generally speaking, unrepentant know-nothings don’t suddenly improve their work when given a second or eighth stab at doing things. They just switch tactics to keep securing their power. In Kentucky, we have many precedents for this.

And that is the real story here: in the fallout of a global Black Lives uprising, a connected non-profit is taking Facebook money to solicit marginalized Hood voices as a means to retain its ill-gotten community access and power.

In the end, pre-Floyd or post-Floyd, real values always trump shape-shifting brands. And by now, we should know enough about CivicLex’s real world values to know they have no business leading a debate on gentrification.

Billie Mallory

Have to beg the question- where are the black faces and voices?

Will Overbeck

I interpreted those Facebook posts by Joe Sonka different. Anyhow, glad you are writing your perspective, but it seems bringing voices together instead of dividing should be the end goal. I like reading your criticism…. For what it is worth, but…

Danny+Mayer

Couple quick things:

(1) The article cited one Twitter post by Joe Sonka. Readers can read for themselves here about whether it primarily focused on dismissing the claim that the city was pushing gentrification of the neighborhood where Taylor was murdered. I say yes; Overbeck says no. (Its title, fwiw, is “‘A false narrative’: Louisville leaders scoff at gentrification claims in Breonna Taylor suit.”)

https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2020/07/06/louisville-leaders-rebut-gentrification-claims-breonna-taylor-police-shooting-case/5382558002/

(2) I think we disagree about which groups are being divisive here, and also the role of journalism, which is about finding the story, not necessarily about bringing people together–though maybe we read different news.

From the penultimate paragraph, here again is the story of CivicLex’s grant:

“[I]n the fallout of a global Black Lives uprising, a connected non-profit is taking Facebook money to solicit marginalized Hood voices as a means to retain its ill-gotten community access and power.”

It’s not divisive to point this out. It’s divisive to do it to begin with.