Editor’s note: This is part two of an inquiry into the Lexington Committee on Housing and Gentrification‘s stated need for authentic community voice . You can read part one here: Story mining the Hood

In one form or fashion, Lexington civic groups have been mining the daily experiences of low income neighborhood residents for generations, and always in the name of progress.

The pattern has remained fairly consistent over the past 90 years: (1) certain city residents, who are empowered, desire the land upon which low income residents reside; (2) a series of progressive commissions, stuffed with progressive reformers and guided by a new professional class of urban planners, get established to apply a specific problem-of-the-day to neighborhoods targeted for reform/removal; these civic groups (3) collect data on those places, and then (4) issue civic road maps that authorize area improvement through some force of redevelopment.

Former University of Kentucky Geographer James Hanlon writes persuasively on the early moments of these commissions. From his 2011 article on Lexington’s mostly black and poor Adamstown residents, whose Depression-era removal cleared the way for construction of UK’s Memorial Coliseum, which would become home to budding coaching legend Adolph Rupp and his nationally-acclaimed Wildcats basketball teams:

In the 1920s, many of these neighborhoods [like Adamstown] came under the scrutiny of urban planners and municipal slum clearance agencies. Newspaper accounts tended to refer to these areas simply as slums, unsightly shacks, or ‘cheaply constructed, unattractive frame dwellings occupied by Negro families,’ but administrative documents and correspondences consistently referred to them by their place names.

For example, the 1924 housing survey listed a number of working-class neighborhoods while emphasizing their relationship with local institutional apparatuses: ‘Chicago Bottom [sic], Brucetown, Davis Bottom [sic], Goodloetown, Yellmantown, have many famous streets and alleys bearing the names of distinguished citizens. These streets are well known to school physicians and nurses, to family welfare and baby milk supply workers, to public health visitors, to the hospitals and sanitorium [sic] and clinics.’

Hanlon, “Spaces of interpretation”

Documents usually beget documents, and eventually, the decades-long cluster of Lexington studies on Hood health, housing stock, sanitation, social services and the like coalesced, after World War II, around a city push for slum clearance and the construction of subsidized public housing. Again, from Hanlon:

Administrative scrutiny continued into the New Deal era and intensified after the passage of the 1949 Federal Housing Act. In 1935, a Kentucky Emergency Relief Administration survey identified Pralltown, Goodloetown, Chicago Bottoms, and Adamstown as slums, and in 1952, Lexington’s Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Agency targeted Pralltown, Davis Bottoms, and Chicago Bottoms for removal.

Hanlon, “Spaces of interpretation”

These early neighborhood studies begat the city’s first two housing projects, Aspendale and Charlotte Court, which were built within the mostly black neighborhoods of the East End and West End, on lands that had been razed in the progressive name of community health.

Two generations later, residents from many of these same neighborhoods would be the recipients of a new round of progressive civic studies, this time to dismantle the affordable housing that had been built through the work of the earlier civic organizations.

The post-Civil Rights Community Voice

While early slum-clearance and other commissions rarely felt the need to solicit community voice, later post-Civil Rights commissions would begin to pay the concept lip service, until by the turn of the millennium, the need to deliver what the community wants had–on paper at least–become a central tenet of all civic development programs, whether public, private, or non-profit directed.

Two Lexington civic commissions created in the 1970s, the Irishtown/Davistown study (1971) and the Pralltown Development Study (1975), demonstrate the growing importance of community voice.

Both studies were prompted by the expanding needs of the University of Kentucky and city of Lexington. The Pralltown neighborhood along South Limestone had long stood in the way of a growing University of Kentucky and its plans for westward expansion across South Limestone. As far back as 1951, the city and university had worked together to prepare the neighborhood for this new, UK-led, development. The 1975 Pralltown study tread much the same territory.

The Irishtown/Davistown study, meanwhile, involved university expansion of a different sort. A generation earlier, the university had utilized slum clearance programs to clear the land along its northern boundary of low-income neighborhoods. That earlier program of slum clearance along Euclid Avenue (since re-named Avenue of Champions), had led to the 1940s construction of Memorial Coliseum, home of the (then all-white) men’s basketball team.

The 1971 Irishtown/Davistown study set in motion the clearing of low income neighborhood lands for the construction of Memorial Coliseum’s successor species–what was to become, in 1977, the 23,000 seat Rupp Arena and its surrounding, mostly vacant, downtown acreage of surface parking lots dedicated to its success.

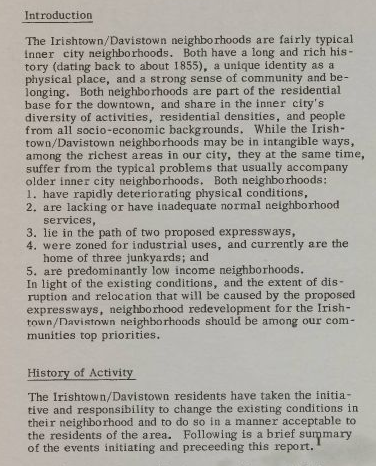

Unlike earlier civic programs, both the Pralltown and Irishtown/Davistown studies of the 1970s emphasized the community-led process that had led to their creation. From the opening of the Irishtown/Davistown study:

The Irishtown/Davistown residents have taken the initiative and responsibility to change the existing conditions in their neighborhood and to do so in a manner acceptable to the residents of the area.

Irishtown/Davistown Neighborhood study (1971)

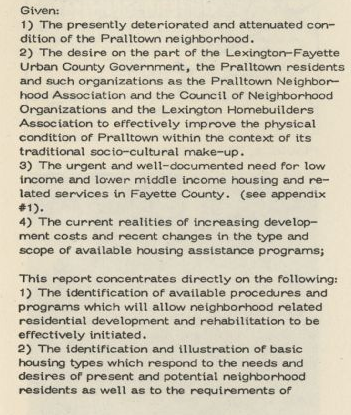

And from the opening of the Pralltown study, listing city objectives:

The desire on the part of the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government, Pralltown residents and such organizations as the Pralltown Neighborhood Association and Council on Neighborhood Organizations, and the Lexington Homebuilders Association to effectively improve the physical condition of Pralltown within the context of its traditional socio-cultural makeup.

Pralltown Development Study (1975)

Both studies show that ‘community voice’ has long been central to the operating process of progressive civic commissions. Don’t let anyone tell you any different: in this university city of over-educated researchers, we do have a well-documented and fairly consistent Hood voice.

Across a half century of time and in a variety of Lexington neighborhoods, communities targeted for special analysis generally express a desire for cultural cohesion, business development, infrastructure upgrades, housing renovation, and the ability to age-in-place.

This isn’t brain surgery, and it doesn’t take a particularly empathetic person to recognize these things. And yet, if we look at the Pralltown and Irishtown/Davistown studies from a 50-year perspective, three things should immediately jump out: Rupp was built, UK expanded, and the social cohesion and economic uplift that the record shows was desired by ‘the community’ never quite materialized.

We can let the civic leaders of these Task Forces off the hook by pretending that the community voice was not addressed, or we can make the much more difficult observation that our civic leaders, who are spawned from some of the most respected (and subsidized) industries in the city, have a deep and abiding history of paying lip service to, and otherwise manipulating, that voice for their own collective benefit.

If we believe their choices are innocently naive, then a simple value-adding of la gente will make things right. Of course, if we find that community voice has been historically manipulated by the same cohort of leaders, what then?

Billie Mallory

The more things change, the more they repeat themselves. Progress to one (who benefits the most) is the devastation of another (who loses everything). Lexington and UK being the one who benefits the most from wiping out villages/hamlets and entire neighborhoods of color and diversity and then they get attitude when called out on it. They have been ‘kneeling on the necks’ of the poor dark-skinned people for centuries until the life drains out of them…

RIP