As we near the end of yet another record-breaking year in political campaign donations, now is a good time to take a look at our own local class of campaign donors. Unlike, say, state and federal elections, whose campaign war chests provide ample fodder for media stories ranging from candidate viability to factional cronyism, local elections in small cities like Lexington generally do not generate a corresponding amount of campaign scrutiny.

This is unfortunate. In a trickle-down world, local government is the seat of power, the big boss-man in charge of doling out those meager, strings-attached funds that get allocated to our communities. And in a country marked by such a vast and impersonable inequality, it is also the only level of government we are genuinely able to access. It stands to reason, therefore, that we citizens should have a sense of who is buttering our local representatives’ bread.

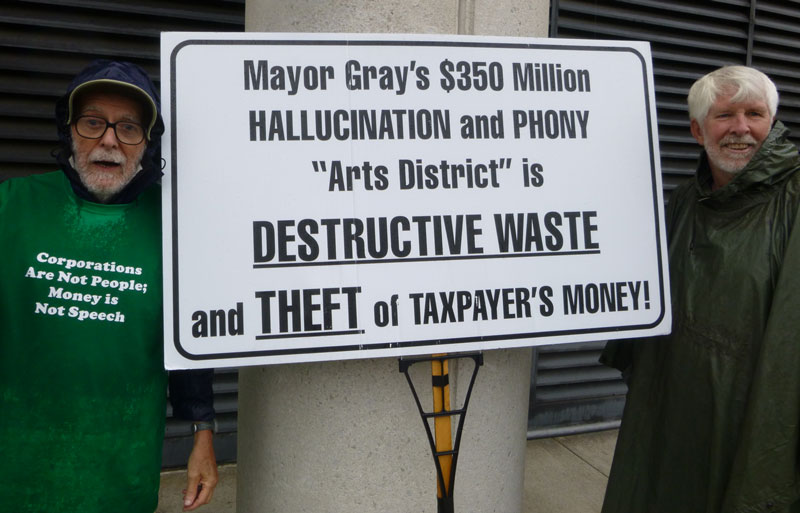

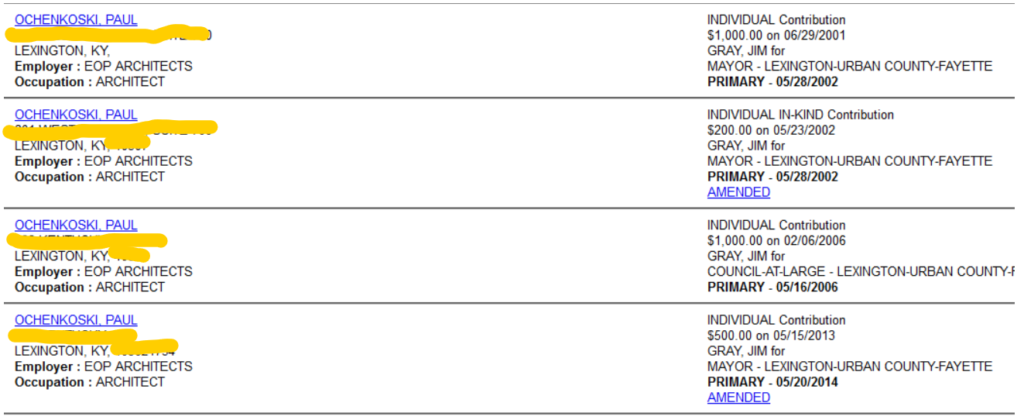

Here in Lexington, I have been tracking local political donations for the past decade, since the Jim Gray v. Jim Newberry mayoral campaign of 2010, which smashed local records for political fundraising.

I come by my hobby honestly: for much of the past decade, my work at North of Center has found me reporting on many of these local political donors in their “civic” roles as non-profit and city board members, or as media-approved community advocates for Rupp Arena upgrades and promoters of local subsidies for art-hotels, urban trail systems, new city halls, and suburban university research parks.

Added to this work, I was connected for some time to the active local chapter of the national Move to Amend organization through a friendship with former University of Kentucky Associate Professor of Management Andy Grimes.

Move to Amend, which grew out of the Citizens United Supreme Court decision allowing corporations (and also non-profits and unions) the ability to participate in electioneering, mostly concerned itself with national and state-wide federal elections, and the dark-money Super PACs that Citizens United seemed to enable. The group’s core thesis, however, rang true at all levels of electioneering: big money perverts our system of electing public servants.

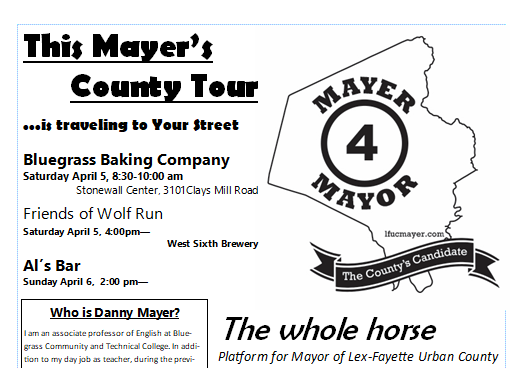

I also ran for local office. In 2014, I was one of three candidates for Lexington Mayor, losing in a landslide in the primary to the infinitely better-funded candidates Jim Gray (former CEO of Gray Construction) and Anthany Beatty (former Lexington Police Chief and current University of Kentucky “Assistant Vice President of Public Safety and Finance & Administration Chief Diversity Officer”).

These different engagements with the city’s political donors have convinced me of the need for a more locally nuanced measure of political speech than our current fixation on high-dollar national electoral campaigns will allow.

What follows is a brief argument for the use of “the Schatzki” as a local measurement of political donor power. I offer it as a tool of analysis for those Fayette Urban Countians who see themselves as neither represented nor engaged by either major national political party, citizens who are instead beginning to plug into the county’s local political structures and need to know, quickly, which donors and voting blocks are supporting which candidates.

The Schatzki: a unit of donor power

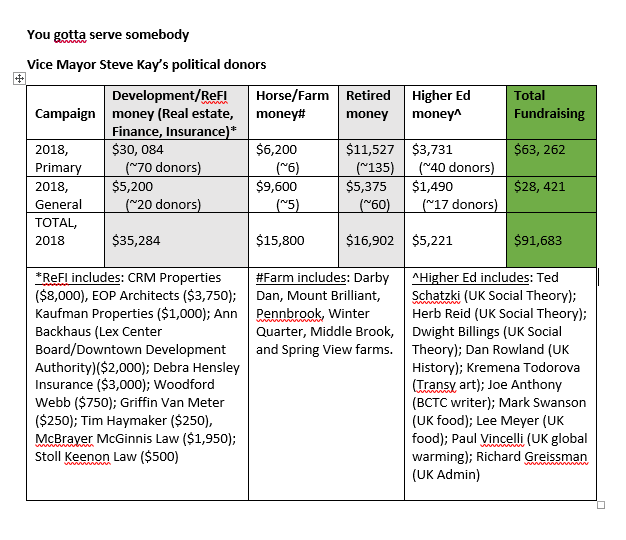

In 2018, in the run-up to the Fayette Urban County (FUC) elections for Lexington’s Mayor and city council, I began to spend many hours on the Kentucky Registry of Election Finance, examining who was funding our local candidates. I didn’t look at every candidate’s donors, but I viewed enough to make a few insights.

Individual contributions to local candidates can vary widely. On the low end, I have seen contributions for as little as $10. At the upper end, a few individual contributions max out at the $2,000 limit per election cycle, or $4,000 total for primary and general election campaigns. (By comparison, individual limits for federal campaigns max out at $2,700 per cycle, or $5,400 for the primary and general elections. Other states allow significantly higher individual thresholds, and as always, the laws are written to be gamed by those with lots of money.)

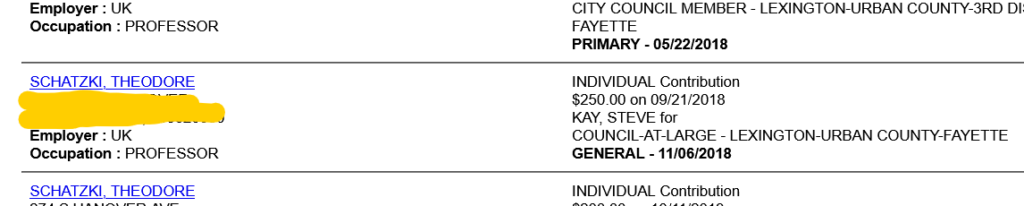

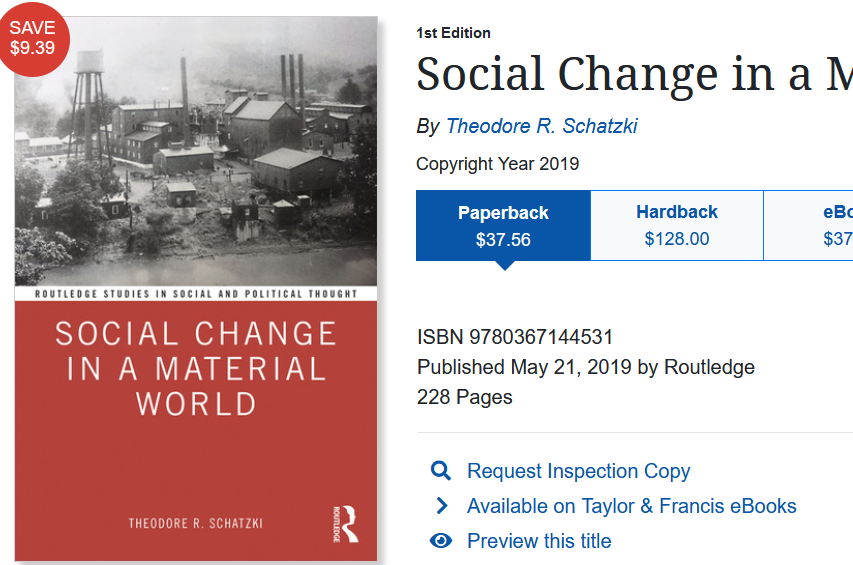

In this city, at least during its 2018 election season, the breaking point between small and large donations seemed to be $250, a unit of political currency I have come to call a “Schatzki.” The Schatzki is so named for the academic Ted Schatzki, co-founder of the left-branded UK Committee on Social Theory, who in the 2018 election cycle donated $250 to the campaign of center-right Vice Mayor Steve Kay.

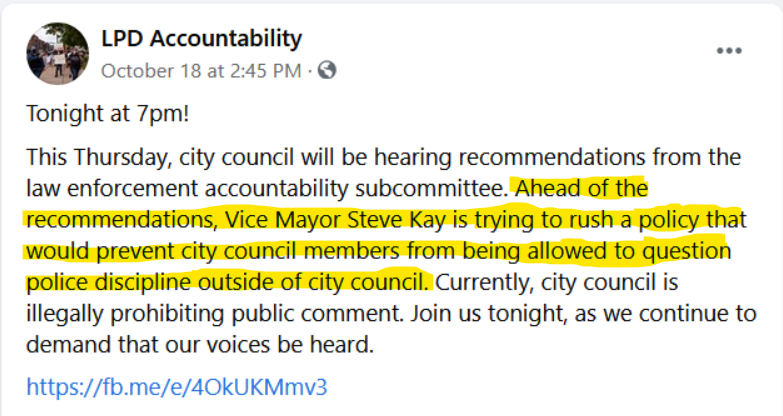

(A note to Lexington Herald Leader readers and Bell Court residents: Vice Mayor Kay’s center-right credentials are not up for debate. While on council, the man greenlighted subsidies to a millionaire liquor heiress and other wealthy area developers; championed a $300 million city/state renovation of a sports arena whose main purpose is to support the $8 million a year UK men’s basketball coach; forced homeless visitors of a day center on Martin Luther King Boulevard to enter through the back door so as to not upset a nearby private prep school; has openly denied the existence of gentrification for going on a decade now; and most recently helped craft on the sly city policies that limit the ability of city council members to pursue information about police discipline cases that will come before council.)

As a base unit of assessment, the Schatzki represents roughly the same amount identified by the Lexington Herald Leader‘s Andy Mead in his coverage of the 2010 Lexington mayoral campaign. During that campaign, Mead cited a press release by then Vice Mayor Jim Gray that “said 1,700 people had contributed to the vice mayor since the campaign began, including 472 who had given $100 or less. The average contribution: Less than $290.”

I have pegged the Schatzki at $250 and not $290 for several reasons. First, nobody actually gives $290, whereas $250 donations are somewhat common–by far the most commonly donated amount between the $150 and $450 contribution ranges. Second, the $250 Schatzki is just easier high-donor math. Four Schatzkis make a grand; eight Schatzkis a maxed-out donor for the current election cycle. This simple math makes the Schatzki easily indexable against things like donor inflation and/or any future increases to maximum individual contributions.

At the same time, the Schatzki remains a significant economic contribution, an amount out of the reach of most regional citizens who might hold interests in the outcome of Fayette Urban County’s political races. Simply put: a Schatzki represents a singular unit of local power in a way that a $10 or $100 political contribution cannot. Multiple $100 donations might (if bundled properly) a Schatzki make, but as stand-alones they do not stand out.

Culturally speaking, the Schatzki underscores both a more flattened local base of powerful donors and the seemingly schizophrenic nature of local political power. Unlike our state and federal elections, which are typically fueled by the direct and indirect contributions of far-off multi-millionaires, local political campaigns by comparison run on significantly smaller budgets and draw upon a substantially more intimate geography of donors. PACs and “dark money” Super PACs, so prevalent in races of national or state significance, also occupy a significantly smaller footprint in local campaigns.

When it comes to local politicking, what stands out is the person, and that person need not be a CEO to be a big fish–merely very well off in relation to the rest of the region.

Ted Schatzki, the man who donated $250 to the re-election campaign of Vice-Mayor Steve Kay, represents one of the key merely well-off constituencies that have capitalized upon this feature of local political funding: higher education’s white collar workforce.

Schatzki is a long-time faculty member at the University of Kentucky, housed first in the Philosophy Department of the UK College of Arts & Sciences and currently in its Department of Geography, where he makes in excess of $200,000 a year. In between stints in these two departments, Schatzki served nearly a decade holding one of those high-cost tongue-twister managerial titles that have sprouted like microgreens at institutions of higher learning across the United States. Officially, Schatzki spent a decade as a “Senior Associate Dean in the College of Arts and Sciences.”

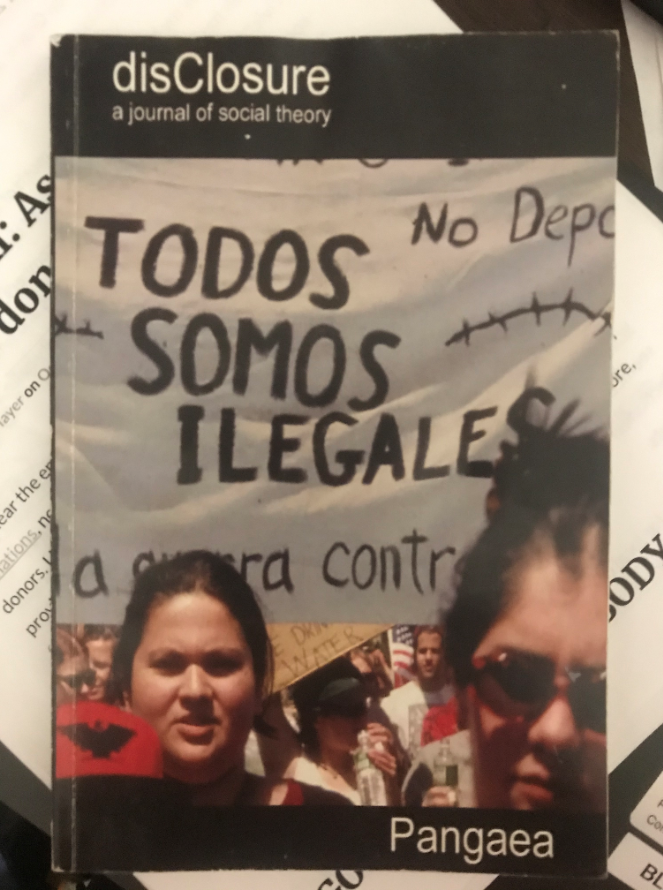

As one of the founding members of the college’s Committee on Social Theory, which has organized talks and published journals on topics ranging from radical democracy and social justice to border crossing and market failure, Schatzki comes with solid lefty-academic credentials. Indeed, much of his ample published writing focuses (theoretically) on social change in a material world.

On the surface, Schatzki’s political support for Kay may appear schizophrenic. How does an old school lefty academic concerned (academically) with social change come to donate an entire Schatzki to a center-right Vice Mayor who, more than just about any other local actor over the past decade, has worked to privatize the Fayette commons and champion the needs of the already-wealthy?

But there is a local logic to the donation. By 2018, when Senior Associate Dean Schatzki made his “full Schatzki” donation to the Steve Kay re-election campaign, the Vice Mayor had shown himself a great friend to Schatzki’s rapidly expanding employer, the University of Kentucky.

By 2018, Kay had voted $250 million for a “gold standard” arena for the university’s Top 10 men’s basketball team–a wonderful brand for attracting a national and global population of students, even liberal-arts students. Kay had championed $20 million in subsidies for a conveniently located downtown modern art hotel to wow all those global scholars jetting into town to deliver talks or perform research at his Top-20-aspiring research university. As late as spring 2018, mere months before Schatzki’s Schatzki, Kay had secured $33 million in local and state Tax Increment Financing subsidies for the university to expand its suburban Coldstream Research Campus.

In addition to being a unit of measurement, then, the Shcatzki identifies local individuals and active voting blocks often left out of our fevered national discussions on the increasing dangers of privatized campaign finance. Far from representing a schizophrenic local political culture that seemingly departs from, say, the national narrative of enlightened academics supporting forward-thinking national candidates (like Biden? like Kamala?), the Schatzki identifies strong geographic consistencies across seemingly disparate voting blocks.

For active citizens residing in the FUC, unfortunately, one thing the Schatzki highlights is an entire well-funded ecosystem of locally regressive progressive voters.

Yong Guan

I know three of those listed under ‘Higher Ed’, two of them well enough for them to speak to me (well, pontificate, opine, and lecture would be more accurate) on a first name basis. And I can say without a single doubt in my mind that they are the two most close-minded, insanely egotistical prima donnas I’ve ever met in this lifetime, one of whom I always describe as not merely an asshole, but something akin to an inflamed boil on a pig’s ass, and to this day when I think of this POS, I feel the most intense rage boiling inside me. To learn that the lot of them are two-faced, pseudo intellectual facilitators of Lexington’s economic elite doesn’t surprise me at all.