On the morning of March 20, 2018, James Brown woke up, most likely ate a good breakfast, and prepared to punch into work as Lexington’s District 1 Council Member. It was a Tuesday. A meeting of the city’s Budget, Finance and Economic Development (B-FED) committee loomed after lunch. There was a re-election campaign to organize.

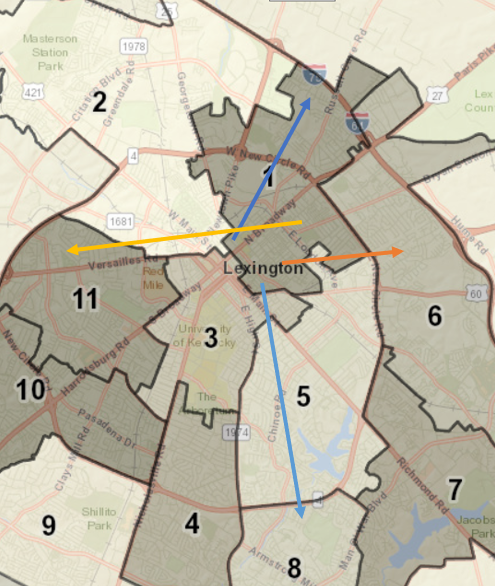

At the B-FED meeting that afternoon, Brown, whose day job is a realtor of residential and commercial property at United Real Estate, delivered a presentation to his fellow council members about a program to support homeowners who live in transitioning neighborhoods (what the rest of the world, in 2018, was calling gentrification). Under Brown’s proposal, the city would provide loans to certain home-owners in certain upscaling communities as a means to help defray the costs of increasing property taxes, loans that the city would recoup upon sale of the property.

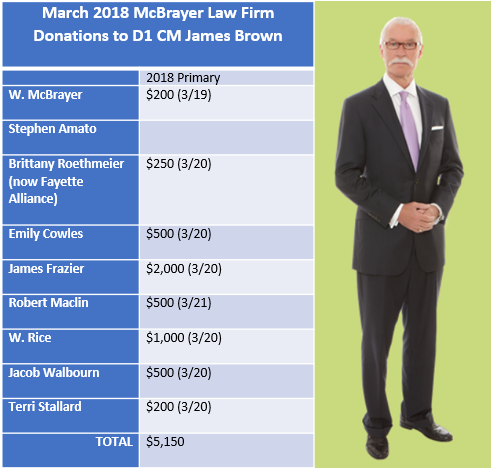

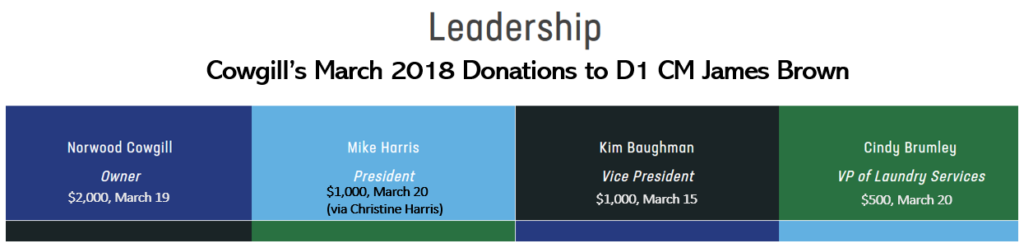

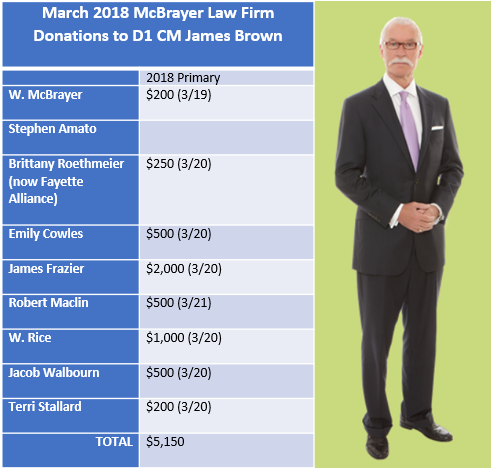

Also on March 20, at some point before or after Brown’s presentation to the B-FED committee (one hopes not during), the District One Council Member received nearly $10,000 in campaign donations from a dozen people related to the prominent Lexington law firm McBrayer, McGinnis, Leslie and Kirkland, and the equally prominent real estate developer Cowgill Properties.

Brown’s apparent one-day haul from people connected to these two companies would amount to nearly half the $21,000 raised during his entire primary campaign, and one-third of the combined $31,000 he would raise during 2018’s primary and general elections. By comparison, Brown’s main opponent in the 2018 race to represent one of the poorest districts in Lexington, Anita Franklin, raised under the $3,000 minimum threshold for reporting campaign donations.

The much-circulated consensus opinion on James Brown is that he is a council member who well represents the First District, a political territory that sits to the north and east of Lexington’s expanding Main Street. This opinion has largely rested on a scant few, well–covered, presentations like the one he delivered on March 20 to the B-FED committee, which claimed to address the very real pressures of gentrification that many of his District One neighborhoods had been experiencing for years.

The Lexington Herald Leader editorial board, for example, would rest much of its October 2018 endorsement of Brown on the council member’s demonstrated ability to “focus attention on the many pressures bearing down on residents of fast gentrifying neighborhoods.” He was, the editorial claimed, “open, a good listener, [and] attuned to neighborhood concerns.”

There is some surface-level truth to the claim of Brown’s good representation of his district. He does occasionally attend meetings in the community. And like a large percentage of the district he represents, Brown is black and not a college graduate. Further, it is certainly true that, since our recent 2020 local elections, Brown is now the only black face (and possibly the lone high school graduate) among Lexington’s 15 elected council members. He represents, in many ways, far more than just his district.

But, as we may soon find out with our first black Vice President, there is a difference between surface representation and actually representing communities. If political donations are a proxy for political representation, as scholars and lay people regularly allege in discussions of our state and national elections, then Brown’s March 20 donor list illuminates the council member’s actual constituency.

And unlike the many poor, black, or non-college District One residents who Brown is said to represent, this submerged constituency skews heavily white, wealthy and highly educated–the settlers pursuing their settler colonialism of D1’s off-Main Street neighborhoods.

What can Brown do for you?

In April 2015, James Brown was appointed District 1 Council Member by then-Mayor Jim Gray when the previous rep, former UK football player Chris Ford, vacated the position to become the Lexington Commissioner of Social Services. Later that same year, Brown would win a special election for the District 1 seat over Jim Burton, a white insurance adjuster and Transylvania University graduate who had moved to the area five years earlier. The win would begin a streak of four comfortable election-day victories. In last month’s elections, Brown ran and won uncontested. (Well, besides my write-in vote for Corey Dunn.)

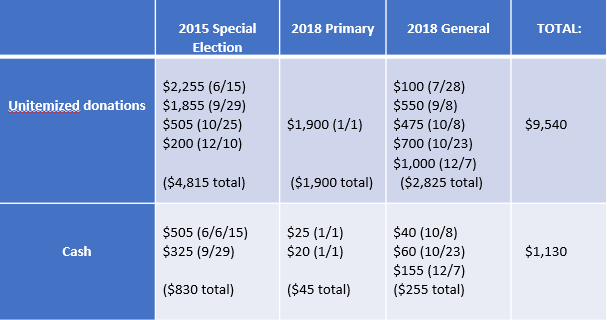

Of the four elections he has run, Brown has only really fund-raised for two of them: the 2015 special election (his first), and the 2018 race against Anita Franklin. In both cases, he significantly out-raised and outspent his opponent, and in both races he was endorsed by the Herald Leader.

The 2015 special election, in which Brown raised $15,000, set a pattern for donations.

As might be expected for a black candidate running for office in a white city, around 12% of Brown’s 2015 donations ($1,800) came from what might be described as Lexington’s black and brown professional class. These donors included Linda Godfrey (KSU professor and direct descendant of the founder of Pricetown’s Mount Calvary Baptist Church), Ed Homes of EHI Consulting, former Kentucky State House Rep Jesse Crenshaw, and the Central American activist-business owner Freddy Peralta.

In addition to donations by Lexington’s black professional class, Brown’s campaign finance records often show a relatively large amount of ‘unitemized’ and cash donations, and 2015 was no exception: $5,600, or around a third of his total that election, came from these two sources.

Unitemized donations represent contributions that fall under the $100 individual threshold requiring candidates to make donor names public. Though anonymous, unitemized contributions are generally understood as a proxy for small-donors. This relatively large amount of such contributions to Brown’s 2015 campaign could suggest some amount of lower-income donor support emanating from the generally low-income District One.

What can Brown do for them?

Of course, unlike those un-itemized donors, we can identify Brown’s largest set of invested stakeholders: Lexington’s real estate and development community, which in 2015 donated over $5,000 to Brown, or 35% of his total haul.

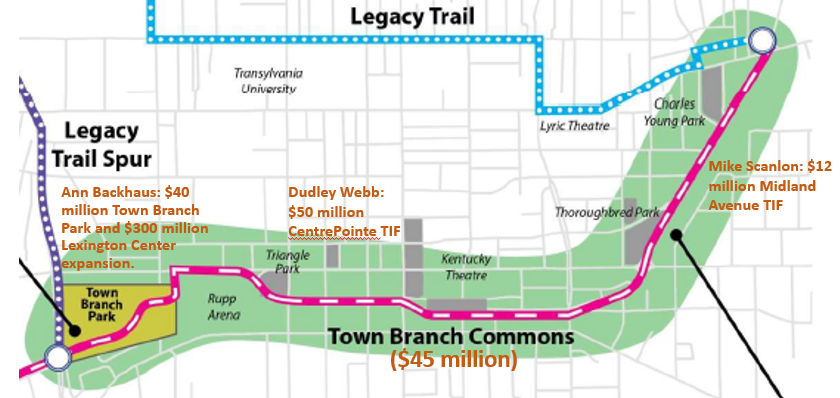

This group of donors included real estate colleagues at Brown’s employer United Real Estate, two different local real estate PACs (HOME PAC and KY Real Estate PAC), former NoLi CDC Board member Bruce Nicol ($500), East End developer and former Vice-Mayor Mike Scanlon ($500), City Center/CenterPointe developer Woodford Webb ($250), and former Lexington Convention Center board member Ann Backhaus ($500).

Of the mostly out-of-district real estate donors listed above, at least three (Backhaus, Webb, and Scanlon) were writing campaign checks to Brown while actively involved in urban developments employing Tax Increment Financing and other public subsidy schemes that, when totaled, amount to nearly a half-billion dollars in city and state development aid.

None of these half-billion dollars in city-subsidized projects included affordable housing, minority business development, or any other direct material benefits for the majority of Main Street-adjacent District One residents who make, on average, less than $30,000 a year.

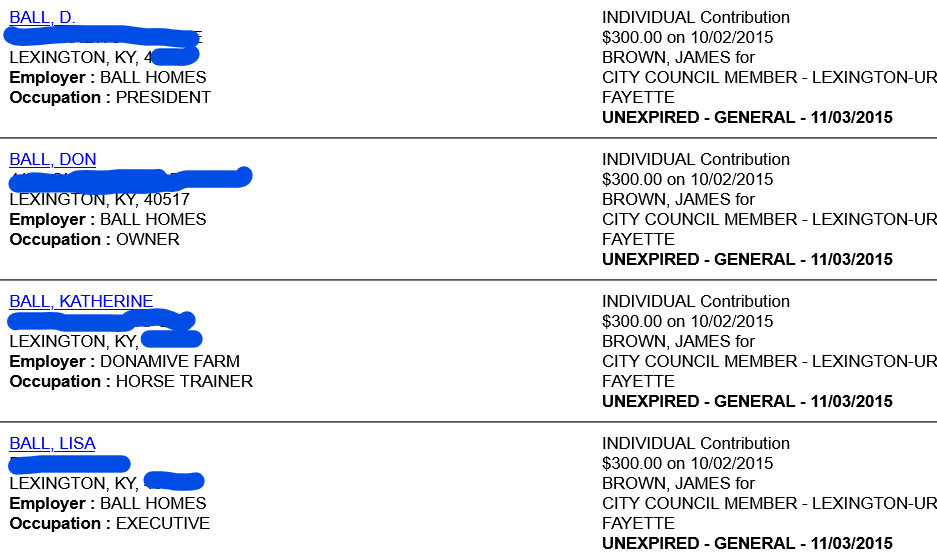

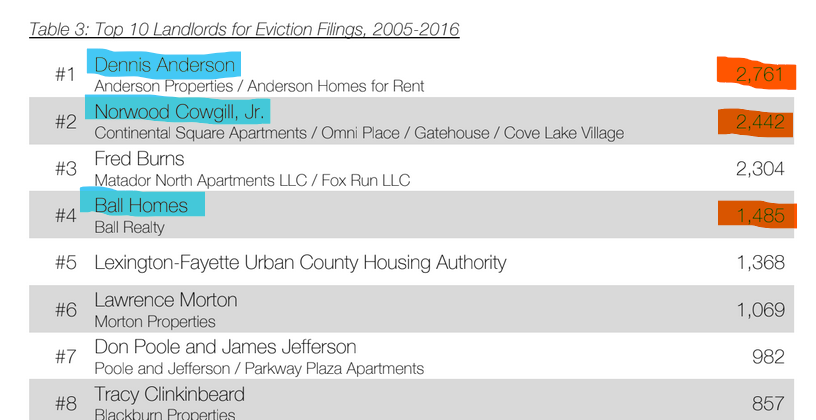

A noticeable subset of Brown’s real estate donors include the developer Dennis Anderson, the Don Ball Homes family, and (in 2018) the Cowgill family developers. Collectively, these three entities have contributed a total of $8,200 across James Brown’s 2015 and 2018 campaigns, or nearly 20% of his entire donation haul as a public D1 rep.

These three developers are also 3 of the top 4 landlords for eviction filings in Fayette County from 2005-2016. (Anderson was also a top-10 purchaser of foreclosed homes during this time period.) Collectively, the three James Brown donors accounted for 6,700 of Fayette County’s nearly 44,000 evictions over that time frame–over 15% of the city’s total evictions.

If James Brown were a white district council member representing the city’s rural horse-centric District 12 (currently represented by white female council member Kathy Plomin), we might cut him some slack as just another privileged status-quo non-actor collecting campaign checks. A Preston Worley.

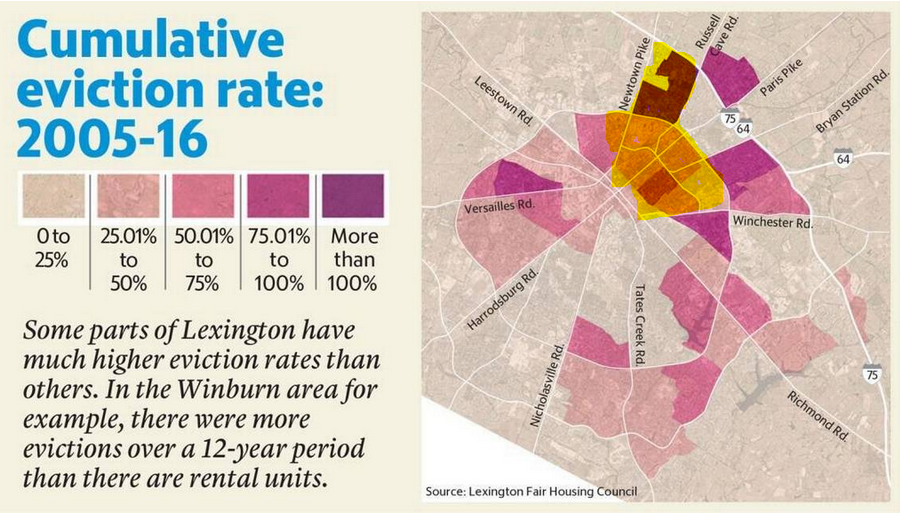

However, Brown’s District One is nearly entirely comprised of high-eviction communities–neighborhoods where evictions account for between 50% and 105% of total available rental units. To take such slumlord money is coal-field level politics, the huckster selling his Appalachian authenticity while collecting Massey and Blankenship campaign checks to perpetuate the profitable strip-mining of devastated communities. (In 2018, Brown would make this metaphor reality by taking nearly $1,000 from the founder of Morgan Worldwide Mining Consultants and a couple lawyers from the mining-industry Bingham, Greenebaum, Doll law firm.)

Taylor Shelton’s 2017 “Foreclosure, Eviction and Housing Instability in Lexington, 2005-2016” provides a bit more context about Brown’s white-collar donor base:

“[W]hile eviction can wreak havoc on individuals, families and neighborhoods regardless of who is doing the evicting, it is evident that the disparate impact comes from a relatively small number of landlords who own a relatively small number of multi-family properties…And while many of the landlords on this list are present due to the simple fact that they are more likely to rent to tenants with modest incomes, the concentration of eviction filings among these landlords remains a cause for concern, and a point of possible intervention

Should the city wish to curb the number of evictions taking place, focusing attention on these landlords and large apartment complexes would represent arguably the easiest way to make a significant impact, as opposed to attempting to monitor and intervene in the workings of hundreds or thousands of ‘mom-and pop’ landlords around the city who may only rarely be involved in eviction proceedings.”

Taylor Shelton, “Foreclosure, eviction, and housing instability”

B-FED’s Kabuki Theatre

Shelton’s report came out in Fall 2017 and was well-covered in the Lexington Herald Leader; it was in fact written for a local nonprofit run by several individuals who would soon serve on a housing task force run by Brown. Like the gentrification of Lexington’s near-Main Street neighborhoods, the large problem of city evictions and rental instability was not necessarily news on March 20, 2018, when Brown delivered his B-FED presentation on how the city could best engage the problem of neighborhoods being gentrified and slummed.

At B-FED, Brown could have followed up on the 2017 suggestion given by Shelton: to focus civic attention on the landlords and large apartment complexes responsible for most of the city’s roughly 4,000 annual evictions as “arguably the easiest way to make a significant impact.”

Brown did no such thing. When given the spotlight in 2018, his presentation focused instead on a poorly researched civic plan from Philadelphia: Tax loans! For certain homeowners! To pay increased property taxes!

If you lived in an at-risk neighborhood and were, in fact, at-risk, the presentation was a clusterfuck, delivered by a man about to run for re-election who, you were being told (mostly by white media outlets), was like you.

As even the councilmember would later acknowledge, his proposal did comically little for homeowners (its intended audience), very few of whom in Lexington were actually at risk of getting priced out of their homes due to property tax increases. At the same time, Brown also whiffed on the far, far greater population of low-income northside renters who are at far, far greater risk of removal from the processes of urban gentrification.

On the other hand, though, below the surface in those deep veins of Lexington capital, Brown’s presentation was wonderfully effective Kabuki theater for both legs of the city’s development industry. A something being done that was, in fact, nothing.

The city would never act on Brown’s proposal, which died in B-FED, but that was always the point. On the same day as his Kabuki performance, Brown received nearly $10,000 in campaign donations from the slumlord developer Norwood Cowgill and a handful of lawyers from the McBrayer law firm that represent his slumlord developer interests.

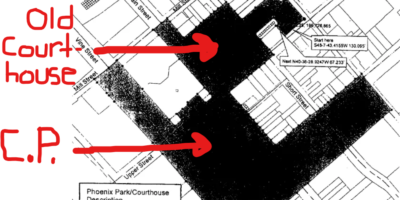

As it turns out, the $10,000 donation-bomb was most likely related to a vote-buying scheme involving a Cowgill proposal to build a new City Hall. That scheme was foiled when a fellow council-member ratted out a competing development company‘s similar vote-buying scheme, and plans for the new City Hall were scrapped amidst the FBI sweeping down on Council chambers on the eve of their final vote.

Of course, if you are black or a high school graduate and living in the northside, or anywhere in this city, what’s the difference, really, between taking donations to secure a $100 million graft to build a new City Hall a block from the East End, and taking them to maintain a more abstract status quo culture that for decades has worked to remove and then ghettoize you about town?

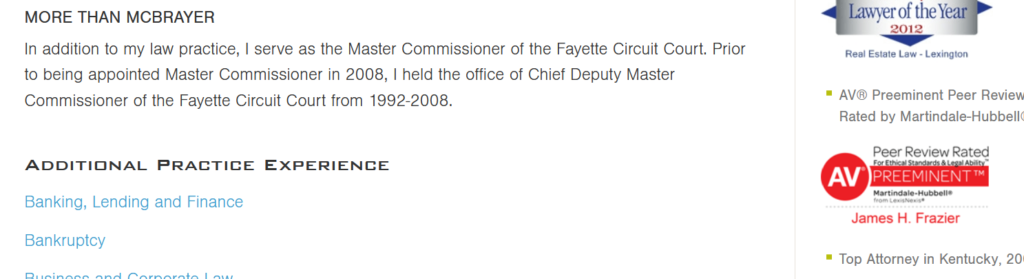

Do such academic and legal distinctions matter? The biggest of Brown’s March 20 McBrayer donations for the city hall graft, $2,000, came from the checkbook of the prominent and award-winning Lexington lawyer James Frazier, who as Fayette Master Commissioner for the past decade has been selling foreclosed homes on the courthouse steps as a form of proud community service.

I mean, c’mon, people.

Billie Mallory

So, my question (actually several)–how many of those donors actually live in 1st district? Nearly all are developers/ professionals but not residents in the poorest of northside neighborhoods.

Why not call gentrification what it is? By any other ‘pretty’ name that may be more acceptable- the impact is still the same in devastating poor neighborhoods by speculative developers (see above). A Task Force that met for more than 2 years, has yet to present recommendations to Council or Administration (some of the above served on that TF- are we seeing a connection yet?). The Housing/ Gentrification sub group of Mayor’s Commission that met for about 2 months came up with very similar recommendations and have submitted theirs, while TF rec’ds still sit on shelf.

Now, as a resident of 1st district how many times have you seen CM Brown in your neighborhood? How many responses have you gotten from emails or other means of inquiry? How many personal dialogues have you had (as an outlier, I assume that you are holding up 1 hand).

So final question is, who does this CM really serve?

Danny Mayer

I can’t speak for other residents, but as a D1 resident myself, I can state unequivocally that James Brown and his administrative assistant have problems returning emails in a professional time-frame (within 3 business days) and with a professional sense of decorum. I know he has made me feel like a second-class citizen since I began contacting him in 2016 on topics related to transit, affordable housing, Tax-Increment Financing, and gentrification..

I imagine neither he nor his assistant treat his out-of-district slumlord donors–or the nonprofits who have partnered with him–in the same way. In this city, some people matter. And others don’t.

Rama Asmani

Why don’t you run to unseat him. Myself I live in the CC d8. I don’t want talk and take no action