Last week, LFUC City Council began public discussions on whether to issue $40 million in Industrial Revenue Bonds (IRBs) to Astana, LLC, a two year old private development company fronted, publicly, by the former collegiate horse-polo star Nik Feldman.

First used in the Depression-era south as a relatively safe way for capital-poor southern states to attract northern industry, IRBs are a type of municipal bond (loan) in which a city or state operates as a sort of pass-through entity for investor/bondholders to loan money to a private business looking to build or expand industrial capacity.

This pass-through arrangement grants private developers access to city or state-issued tax-free municipal bonds (good for investor/bondholders) that in turn lower the financing costs of the industrial project (good for private developer). In a nod to the sort of heads I win! tails I win! nature of these supply-side development deals, IRBs typically require, per federal law, a legal arrangement that enables the developer to pay no property taxes on the development for the duration of the bond.

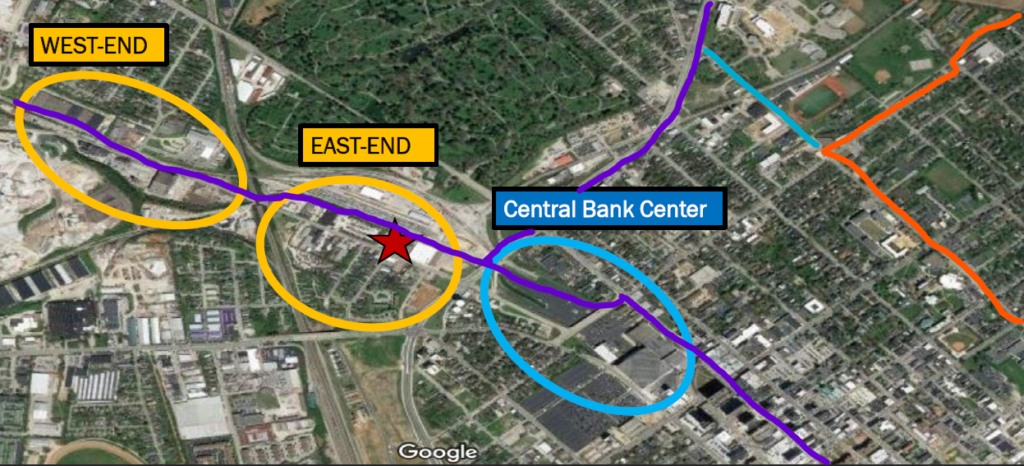

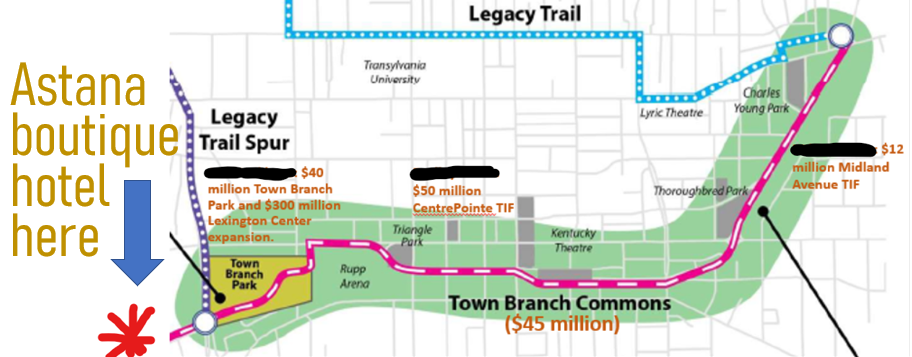

In the case of the $40 million, 40-year Astana IRB being considered by Council, the industrial capacity being generated for Lexington includes a 100-125 room boutique hotel with rooftop bar and on-site brewery. The development will sit on several apparently capital-poor acres of urban land, surrounded by, on its east flank, the soon to be completed $350 million Rupp Arena and Town Branch Commons Park developments, and on its west, the Distillery District. The Town Branch Trail, one of only two trans-neighborhood bike trails in the city, will run past its front door.

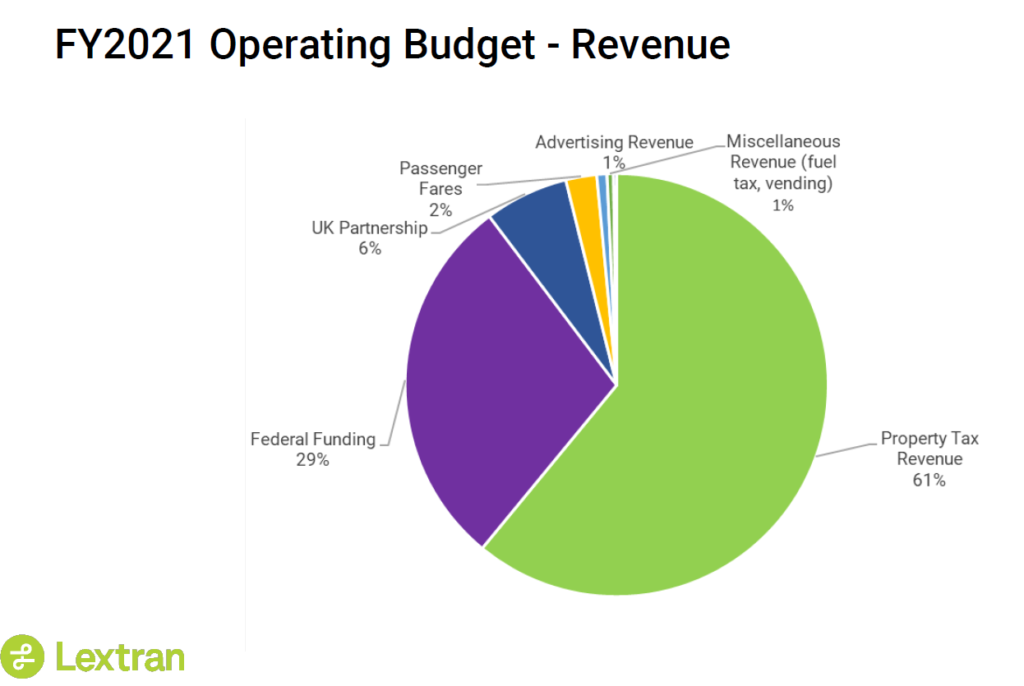

Last Tuesday’s Council meeting, held May 25, was supposed to include the first of three required readings for Council to take a final vote and thereby enact the Astana IRB as binding city ordinance sometime by the second week of June. That plan was disrupted when, during the meeting time allotted to citizen comments, several members representing the Lexington Public Library objected to the IRB on the grounds that it would negatively impact their annual funding. (The Public Library is among a number of city public services whose annual budget comes chiefly from property taxes, which the IRB would release Astana from paying for 40 years.)

As a result of those objections, about which you can read more here, Council has decided to hold off on a first reading of the IRB proposal until June 10. Mainly, this is to give Feldman and his investors time to strike what is known as a “Payment in Lieu of Taxes” (PILOT) deal with the library and LexTran, something Astana had already done with Fayette County Public Schools—yet another city service that, like the library and LexTran, is funded chiefly through city property taxes.

Judging by the first round of questions that Council Members posed to Feldman and his legal representative, Bill Lear, the Astana delay is likely to be pro forma. Mixed among the, by my count, 10 different council member declarations of support for the project, there were airball questions about parking (they’ve got more than required, CMs Lamb and Baxter), about bike/ped connections (did you miss the whole “Town Branch Trail runs right through it” part of the presentation, there, CM LeGris?), and about the hotel’s exact location. The comparatively concerned CMs (Sheehan, Kay), meanwhile, asked whether Astana planned to meet further with LexTran and the library, and to explain the company’s plans to mitigate the city’s loss to its property tax rolls (Kay, Worley).

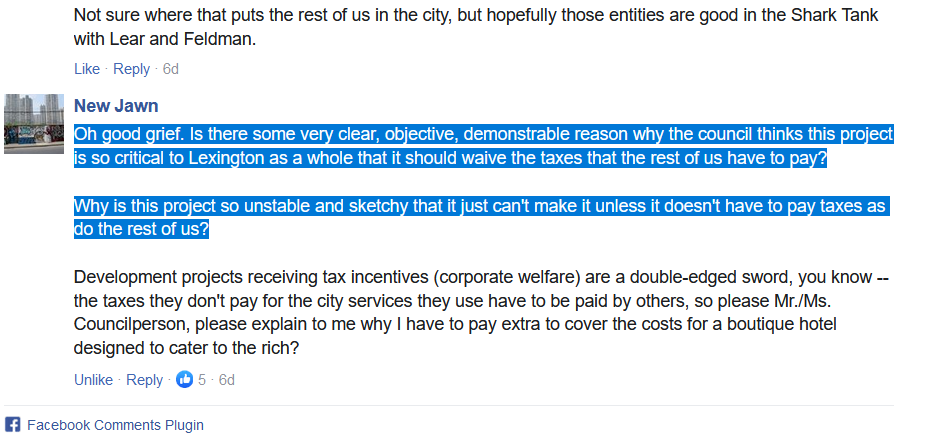

Conspicuously, though, all council members declined to ask of Feldman or Lear what we might simply identify as the obvious question. Here is that question posed by Lexington Herald Leader commenter New Jawn:

Oh good grief. Is there some very clear, objective, demonstrable reason why the council thinks this project is so critical to Lexington as a whole that it should waive the taxes that the rest of us have to pay? Why is this project so unstable and sketchy that it just can’t make it unless it doesn’t have to pay taxes as do the rest of us?

New Jawn

I plan to return to the subject of IRBs in a few future articles. In the meantime, here are two quick takeaways to add to New Jawn’s two reasonable though unasked questions. With Council not taking up the Astana IRB until June 10, you’ve got a week or so to contact them and ensure they voice your concerns–and not just the public library’s concerns–the next time they all get together for a pow-wow.

June 10? June 15? What’s in a date?

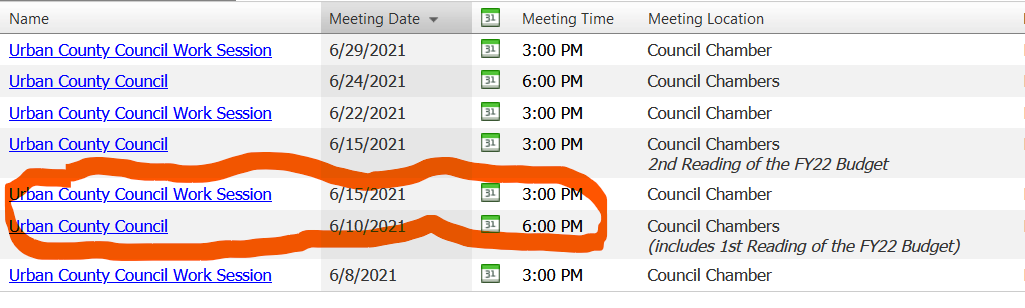

What were council members jawing about if not Jawn’s questions? A surprising amount of IRB debate centered merely on choosing the new date for the first of the three required public Astana readings. Specifically, the civic jawing centered on the dates June 10 and June 15.

Vice Mayor Steve Kay began this discussion through a motion to push Astana’s first-reading onto its June 15 meeting agenda. This came at the beginning of the meeting, before Astana or any other scheduled presentation and after the citizen comments from representatives of the public library.

June 15, Kay argued, would give three weeks for representatives from the public library and LexTran to create their own PILOT deals with Astana. For a 9-minute stretch, Kay’s motion was discussed, amended by CM Lamb and later killed off on a parliamentary procedure to allow Astana to give its presentation without an official council first reading.

The rescheduling issue would reappear, however, after the Astana presentation in the form of a motion by District 2 CM Josh McCurn, who seems to be the Astana project’s chief cheerleader. McCurn’s motion differed from Kay’s in that it moved Astana’s first reading to June 10, a single meeting earlier than Kay’s June 15 proposal. Adjudication and voting on this final decision–the date for a future meeting–took another 5 minutes.

June 10? June 15? What gives?

The surface reason had to do with timing. In its just-finished presentation to council, Feldman had made Astana’s case for urgency. Building costs were rapidly rising, Feldman stated, which could increase production costs by 10-15%. Further, Feldman suggested that the city had a vested interest in having his Astana hotel fully operational. As a decade of concerted civic work and $300 million in city investments like Rupp Arena, the Convention Center and the Town Branch Commons begin to come online next year, city leaders need a place like Astana’s hotel to put all those people they imagine will visit.

City ordinances must have three readings, and there must be at least 14 days between the first and last readings for public comment. This is the law, and following this law for a June 15 first-reading would push the final IRB vote into July. Time—even a week!—was of the essence.

For the record, Council voted 14-1 to support the not even a week! motion by McCurn. June 10 will be the first Astana hotel reading, and as everyone wanted, everything will be decided before the 4th of July break.

(No CM considered the notion that it was such a bad idea to stretch into mid-July or beyond this $40 million civic decision regarding a virtually first run-in with a new, very large public financing mechanism. In fact, the city brought on one of its lawyers to say, that yes, well, IRBs are something that we were thinking we’d take a look at more closely in the Fall to see how we could tweak them—once we get past voting on this first one real quick. Not a CM blinked. I shit you not.)

It was also all likely Kabuki Calendar Theater, something to debate while not debating Jawn. It never got mentioned during the meeting, though I’m sure Astana knew, as did Bill Lear and several of the Council members, of another quirk–a calendar quirk–in Kentucky’s awarding of Industrial Revenue Bonds.

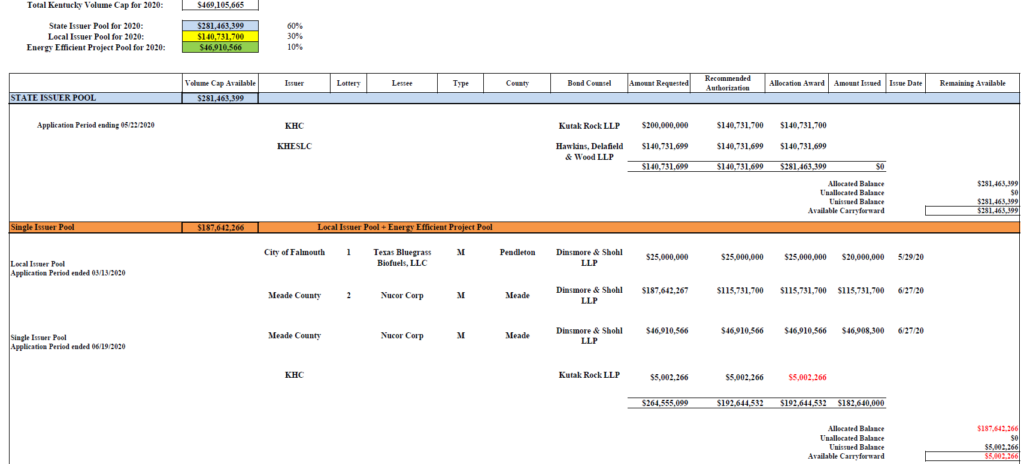

Though administered by state and local governments, the tax breaks associated with IRBs are technically federal tax breaks. In part because state and local governments tended to hand IRBs out like candy, the federal government ultimately capped its funding for them sometime in the 1980s. Today, the federal government grants states an annual IRB allotment based on population.

Kentucky’s 2021 IRB allotment is $492, 497, 620, which gets divided into 3 tranches: 60% ($295 million) goes into the State Issuer pool, 30% ($148 million) into the Local Issuer pool, and 10% ($50 million) into an Energy Efficient Project pool. Astana’s hotel will draw from the $148 million Local Issuer pool, though it may have missed the March 12 deadline to submit its proposal to the Kentucky Private Activity Bond Allocation Committee (K-PABA).

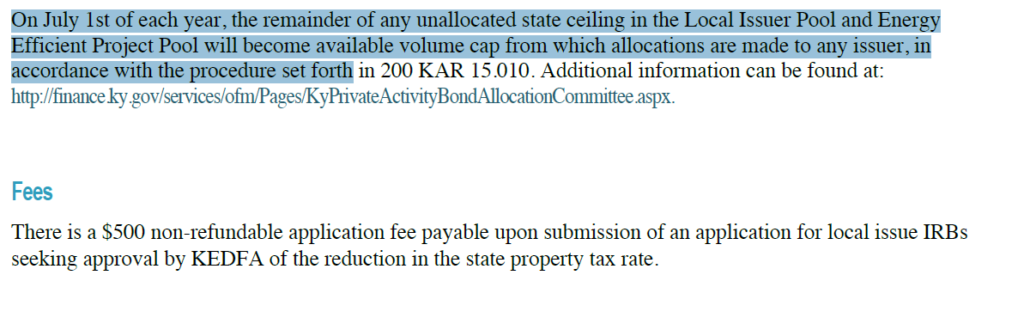

But things change on—ding!ding!ding!—July 1. From a 2016 Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development fact sheet. The emphasis is mine:

On July 1st of each year, the remainder of any unallocated state ceiling in the Local Issuer Pool and Energy Efficient Project Pool will become available volume cap from which allocations are made to any issuer, in accordance with the procedure set forth in 200 KAR 15.010.

Competition among other IRB projects across the state for this available money dump, I’m sure, will be fierce. Astana’s application, meanwhile, is pretty weak as far as “industrial” projects go. Though it may check some, the boutique hotel does not check many public welfare-enhancing, industrial capacity-building boxes. By mid-July, all that discount money could already be spoken for.

Here for example are the 5 projects awarded IRB bonds last year. None were awarded after June 27.

One can see why Feldman and his team want to rush things, and why a June 10 first-reading is something CM McCurn, and most likely a few others, wanted to spend our Council time fighting for.

Test case for the next gen TIF

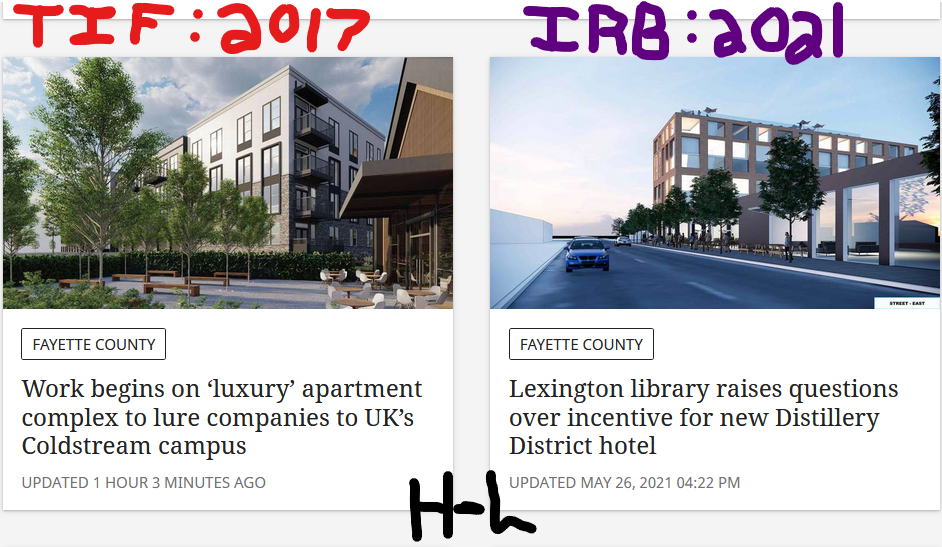

One thing is fast becoming clear: the Astana IRB is a test-case development project. IRBs are being floated—both by Council and by Astana’s Stoll Keenan Ogden public finance team, led by Keeneland Trustee Bill Lear—as a replacement for Tax Increment Financing (TIF), which was the public-private partnership mechanism most favored during last decade’s feed-the-rich building boom.

I am not speaking metaphorically here. Check out Lear speaking to Council last week. (Emphasis mine):

Lexington has not used IRBs in this way for many years…The evolution of economic development programs basically changed in the mid-80s into what I call the state economic development alphabet programs that had both local government and state participation. Then they evolved into what you know as TIFs, which are both state and local, and that involve more than just property taxes. And this government policy-wise has wanted to move away from TIFs, so this is a lesser-included type of incentive.

It doesn’t take much to read between the lines. Financially, intellectually, geographically, the Lexington TIF market is at present saturated—the populace just doesn’t believe the TIF voodoo any longer. When the Lexington Herald Leader’s Linda Blackford can define TIFs as “corporate socialism,” you know that their time in this city may be up, for a while at least.

This is a key context for understanding Council’s Astana deliberations, and why its roll out seems so clumsy: denied one subsidy, city leaders have had to reach into their bag of financial tricks. What they pulled out is the mid-century modern version of TIF welfarism, the Industrial Revenue Bond.

You can see this TIF-to-IRB transition visually, if unironically, in this front-page snapshot taken last week from our Paper of Record, wherein UK’s Coldstream Campus (the last TIF awarded, in 2017) stands next to the report on the Astana IRB, the city’s first IRB since the MTV era.

I’ll have more later on the TIF/IRB comparison and its place in the Astana debate. It has some resonance with the $48 million CentrePointe TIF that passed in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Like CentrePointe, Astana is pecking around the edges of a post-recession possible. Can the LLC convince our 15 elected council members that a boutique hotel, located in what is already the most expensive and already-subsidized part of the city, represents a good opportunity for leveraging this city’s limited municipal power?

CentrePointe made its argument successfully, twice—in 2009 and again in 2013. It passed when city leaders, speaking for the community, fixated on the building’s aesthetics rather than on the convoluted financing scheme that was being sold to the public as revenue neutral. CentrePointe’s success opened the floodgates for last decade’s thoughtless run of publicly subsidized urban projects that have defined the Make Lexington Great Again movement—including, as it happens, that boutique modern art hotel located on the other side of Rupp: 21C.

As with the CentrePointe gambit, if Astana can get its government-issued bonds to build its boutique hotel, the sky’s the limit for this new and upcoming generation of developers, horse riders like Feldman, who by hook or crook can continue to work those large subsidies that only the select few can access.

Yong Guan

In 2020, Astana received approval to recover $7.2 million in sales taxes as an incentive under the Tourism Development Act. To do so, it is my understanding that they had to make the case that the boutique hotel will somehow be a part of the convention center, which seems a bit of a stretch, but then no one on the board is going to look too closely or ask many questions.

Danny Mayer

Crikey Yong, now I have to start a new research front into the Tourism Development Act! I have a summer to enjoy and rivers to paddle!!! Seriously, though, can you post or send along (Mayer.Danny@gmail.com) the link to the approval for the subsidies?

Any other intrepid local researchers with tips for this or any other stories can do the same, either in a post or via email to me.

Yong Guan

It’s a gag-worthy list. Enjoy?

https://www.kentuckytourism.com/sites/default/files/2020-12/LRC%20KTDA%20Report%20-%20Updated%20Sep%202020.pdf