Town Branch by rheotaxis, part 1

By Danny Mayer

Kentucke, once bloody ground, hunting Eden for native tongues apologetically eliminating buffalo for sustenance. Not sport or profit or pleasure.

–Frank X Walker

In the spring of ‘79, a pack of colonialists led by Colonel Robert Patterson exited their fort at Harrod’s Town, a bleak wooden western outpost incised into the recently formed Fincastle County of post-colonial Virginia, with orders to establish a garrison inside the vast canelands that temptingly rolled north off the palisades that lined the far banks of the Kentucky River.

For the Pennsylvania men exiting Fort Harrod, as for the North Carolinians immigrating to Fort Boonesborough and Saint Asaphs, dominion over the rich north land lying between the Kentucky and Ohio Rivers had proven particularly difficult. Shawnee, Mingo, Miami, and a clutch of other area residents had for some time made homes along several of the south-running Ohio River tributaries that debauched into La Belle Riviere from the north. These groups still claimed the commonwealth as a commonland, a hunting and commerce grounds held in usufruct by Indian, some French, and the odd colonial shareholder. Encroachment on the commons by tree-hacking, game-destroying, compass-wielding Pennsylvanians, Virginians, and North Carolinians had met some resistance. For the half decade preceding Patterson’s historic northern incursion, a cartographic truce had emerged: to the south of the protective girdle of the Kentucky River, colonists; to the north of the Ohio, Indians; and in between, the canelands.

This is not to say the frontier Colonel was unfamiliar with the territory. He and many of his 25-man party had spent considerable time over the previous five years across the river surveying what, even in April 1779, was still unstable land. Most had entered Kentucky illegally under a Crown rule that since 1769 had banned development into the western frontier, and they had come in the employment of large corporate land companies who, in claiming tens of thousands of acres for themselves, had illegally negotiated partial and conflicting treaties with the commonwealth’s many tribal claimants.

But as Patterson rode away from Fort Harrod that April, he did so under the rule of an altogether different government. This one was located closer, in the rebel colony of Virginia, and within the month it would issue a new land law claiming for itself sovereign title over the land of Kentucky, a legal declaration that created for the coastal American colony an added income source to help fund its war with the British. The law would create a crude and inefficient mechanism for legalizing land claims made the previous decade on the Kentucky frontier. The land law represented a window of opportunity for the small population of retired militia, squatters, mad farmers, game hunters, and adventurous second sons of European wealth who had entered the commonlands between 1769 and 1779. It allowed them all to log 400-acre claims upon the territory so long as they could provide a legitimate survey and evidence of first improvement. It would also grant them access to another 1000 acres of contiguous land, sold like the original allotments at dirt-rate government prices. (Any land left unclaimed by a set date would revert to Virginia, which would sell it in hunks to individuals or be used as pension for soldiers fighting the revolution.)

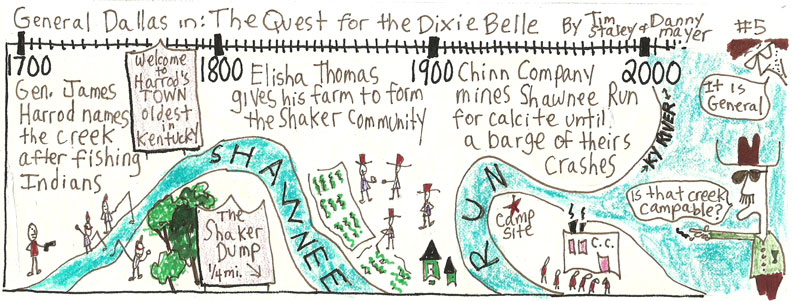

Perhaps sensing the coming change, after Patterson’s party crossed the river, most likely at calcite-rich Shawnee Run, it made haste to an area surrounding the headwaters of a small fork in the greater Elkhorn River watershed in present day Fayette County, on ambiguous territory close-by land claims previously registered by the Colonel and some others, including William McConnell, John Maxwell, John Todd, and James Masterson.

Patterson ordered encampment two miles east of the McConnell claim at a series of springs “whose grateful waters,” the dependably florid local historian G.W. Ranck records in 1872, “in an unusual volume emptied into a stream nearby, whose green banks were gemmed with the brightest flowers.” The next morning, April 17, the men set to improving the immediate area. In defense of red men, wild panthers, and cold weather, they hacked down bur oak, blue ash, and pignut. The astors and trillium were sacrificed without notice to dragged logs, pastured hogs, a few channeled pikes. Within the week, the local historian Lewis Collins would observe in 1848, the men had constructed “a solitary blockhouse, with some adjacent defences, the forlorn hope of advancing civilization.”

Soon after Lexington’s founding, a group of settlers with an eye for the main chance who hailed from the fort at Boonesborough, North Carolinians mostly, would cut a second outpost in the wilderness to the north of Lexington. This station, Bryan’s Station, along with Strode’s near present-day Winchester, would buttress Fort Lexington from native attacks. “Though the discipline about the fort is said never to have been very rigid, nor the stockade kept in strict order,” Ranck writes of Lexington’s foundational settlement, it “escaped any serious danger from Indian attack.” Its new residents would spend the historically cold winter of 1779-80—a winter that would find General George Washington and his army of barefooted rebels plotting a mountain range away at Valley Forge, and, considerably closer, Dan’l and Rebecca Boone sugaring together along the bottoms of the Fayette County creek currently bearing their name—flaccidly commanding the fort’s springs from Indian attacks, hunting, and otherwise asserting territorial weight.

Ultimately the new land law would lead, Collins argues in Historical Sketches of Kentucky, to “a flood of immigration” and a radical transformation of the area. “The hunters of the elk and buffalo were now succeeded by the more ravenous hunters of land; in the pursuit, they fearlessly braved the hatchet of the Indian and the privations of the forest. The surveyor’s chain and compass were seen in the woods as frequently as the rifle; and during the years 1779-80-81, the great and all-absorbing object in Kentucky was to enter, survey, and obtain a patent, for the richest sections of land.”

“Indian hostilities were rife during the whole of this period,” Collins concludes, “but these only formed episodes in the great drama.”

Chief among its early peers, Lexington prospered from the great drama. The fort fast became a crossroads for south-scurrying Pennsylvanians floating down the Ohio, and for north-tromping Virginians angling through the Cumberland Gap. Within two years of its founding as in unmarked territory, May 6, 1781, Lexington was granted a city charter by the powers vested in the fledgling state of Virginia. From a handful of shingled private land-claims, the Charter carved 640 public acres for city streets and a number of city lots for resale to immigrants. Seven men, Robert Patterson, John Todd, and William McConnell included, were granted each fee simple rights to an additional 70 acres of land immediately surrounding the Lexington 640.

In what might go down as the second largest all-time bummer deal in county history, the Charter traded away an entire county of commonlands in exchange for civilization, roads, and a two acre commons located just outside the original fort walls.

The Lexington springs, meanwhile, didn’t fare much better. Once free-flowing, they were immediately damned and fortified as a first act of Lexington development. As the settlement grew and the fort was removed, Ranck writes, “the [fort] spring was deepened and walled up for the benefit of the whole town, a large tank for horses was made to receive its surplus water, and for many years, under the familiar name, ‘the public spring,’ it was known far and wide.” Eventually, though, like the rest of the springs in the area, building construction along Main Street swallowed it, though presumably, under even those private constructions, the once public spring flows still.

Part 2: “Carve/2000-2010“

Part 3: “Clean/February 2009“

Part 4: “Reveal/September 28, 2011” will be updated soon.

View all four parts together at Town Branch by rheotaxis.

Some essays have been revised in moving from their print to online versions. You can find print versions of this article archived under previous issues. Town Branch by rheotaxis was published June 2013.

Leave a Reply