Town branch by rheotaxis, part 3

By Danny Mayer

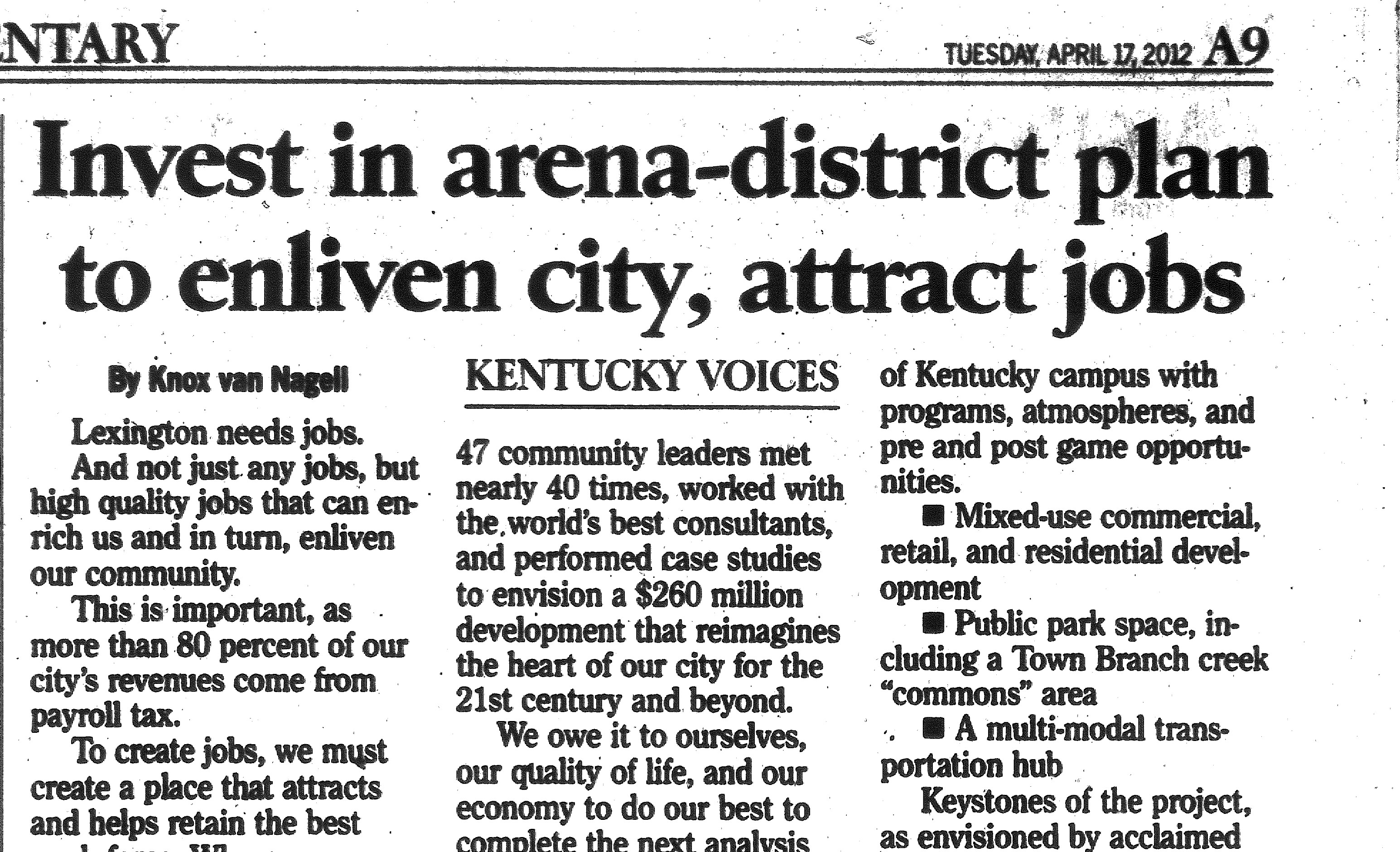

Reveal, Clean, Carve, Connect is a strategy that ties the nuances of Lexington’s rich substrata to development potentials on its surface.

–From Reviving Town Branch, Scape/Landscape Architecture Team

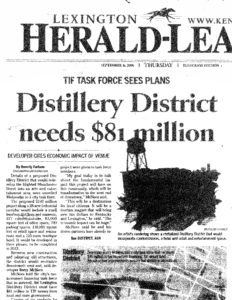

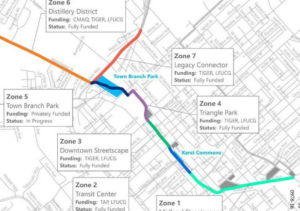

In February, 2009, the Kentucky Economic Development Finance Authority (KEDFA) delivered preliminary approval for the creation of two Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts in downtown Lexington: the 14.25 acre Phoenix Park/Courthouse development and the 25 acre Distillery District. Combined, the two developments projected to cost their developers $490 million to complete, of which the city and state had committed to rebate up to $135 million—or about $3.4 million per downtown acre.

The rebate would come in the form of “tax increments,” future tax breaks amounting to the difference between what an area generates in “today’s” taxes and what taxes it projects to generate at some point in the future. In both the Phoenix Park and Distillery District TIF districts, developers could be expected to recoup up to 80% of future increments for any property, sales, and income taxes that could conceivably be connected to their sites.

According to KDFA projections, the two developers could expect an average annual combined local and state tax rebate of nearly $7 million dollars a year.

For twenty years. (Thirty for the Phoenix Park TIF.)

Welfare for rich people

Llike many recent financial products, TIF seems designed to project obfuscation. It is best to imagine TIF on a personal level.

Boiled down, your tax increment represents the difference between what you pay now in local and state taxes, and what you think you will pay at some point a decade or two into the future. Remember, these are projections. No need to harness yourself to data. Think American:

Do you believe your property’s value will increase over the next 20 years? Expect to make some big purchases during the next couple decades? Do you believe your personal income will rise between now and 2030? How about that small business you’ve just started? Expecting it to grow and pay more in corporate income taxes over the coming quarter century?

Great! Your tax increments project to be positive!

Just don’t go looking to the state for any handouts. Only certain people can leverage their tax increment projections for personal gain. TIF funds are only available to developers whose projects exceed $10-25 million.

In a reversal of the notorious private sector practice of red-lining, TIF subsidies are geographically tied to specific, mostly urban, areas. If your business plans fall outside of designated TIF zones, it does not matter how much money you plan to invest. You cannot apply. (A variety of amendments to the law have diluted this requirement, including a 2011 law expanding TIF’s to military bases and university office parks like Cold Stream Campus, operated by that billion-dollar non-profit land corporation, the University of Kentucky.

In a neoliberal world of public-private partnerships, TIF is new age IMBYism at its finest: a trickle-down governmental green-lining whose most direct effect is to bolster the bottom-lines of the already-wealthy. It’s a fuck tomorrow’s wee Peters to overpay today’s fat Pauls kind of strategy.

Today’s fat Pauls benefit in two chief ways. Long-term, TIFs enhance profits at the margins, which is how most private businesses achieve success. TIFs do this by creating separate tax districts within the city that redirects up to 80% of the fiefdom’s increased property, income, and sales taxes. In other less greedy times, we might expect this tax growth to flow back into general funds, be deliberated upon by wise and judicious leaders, and then disbursed for city-wide needs. In the era of TIF, however, this tax growth is “captured” and handed back to our fat Paul’s. For most TIFs, this margin-enhancer will occur over a period of 20-30 years.

TIFs also serve our portly Paul’s short-term needs. Developers may finance the source project with some of their own money, but most TIF-related projects rely upon a mix of borrowed money and public tax commitments to secure investors and placate bond-rating agencies. The short-term leverage provided by TIF serves to legitimize bad projects by inflating the scope, size, and cost of them.

Consider CentrePointe. In the case of what is officially “the Phoenix Park/Courthouse TIF,” the developers initially asked for $112 million in future tax-increments for a variety of nearby improvements. In theory, these represented pressing public infrastructure needs: a tunnel across Limestone to link the proposed CentrePointe high rise development with Phoenix Park, a pedway across Upper Street to the Financial Center garage, a 331-space parking garage beneath Phoenix Park, a renovated courthouse, and an enclosed Farmer’s Market location.

A mere seven months later, September 2009, the list of publicly funded improvements did not change—but the TIF costs had dropped to $70 million. The project was so leveraged that a fluctuation in the project’s borrowing costs had created a $42 million drop in TIF commitments.

By 2013, the list of Phoenix Park/Courthouse TIF projects has been trimmed significantly. No more Farmer’s Market. Put a hold on the courthouse renovations. Forget the pedway and tunnel. From the original list of public projects, just a private underground parking garage remains—and most of this garage will exclusively service CentrePointe tenants. Whatever tax growth the Courthouse/Phoenix Park TIF promises to bring the city, most of it seems destined to pay off an upscale, out-of-market underground parking garage to which the public will have little access.

Kentucky TIF

While the Distillery District and Phoenix Park were Lexington’s first tax-increment zones, TIF hit the commonwealth two years earlier when state leaders went looking for creative ways to greenline the construction of downtown Louisville’s YUM! Center, home of the Louisville Cardinals.

Louisville, whose revitalized urban experience has recently purchased it the accolades of a variety of travel and food publications, was the earliest and most active user of Commonwealth TIF funds. Of the nine TIF projects approved prior to 2009 by Kentucky’s Cabinet for Economic Development, seven listed a Louisville location.

Though some Louisville TIF projects ultimately went inactive, the $2.7 billion dollar total projected cost for the nine urban projects was underwritten by $1.5 billion in pledged future state and local tax increments. On a per acre basis, the 4,938.3 acres covered under KEFDA’s Lousville TIF districts had redevelopment cost projections that averaged $546,746.85 per acre, of which the state projected to rebate $303,748.24 in taxes.

Since the Phoenix Park and Distillery District TIF districts, KEFDA has approved more Lexington TIF projects. Downtown, there is the $500,000 TIF commitment for the boutique art museum hotel 21C, which sits across Main Street from the CentrePointe (Phoenix Park) TIF.

Other projects are forthcoming.

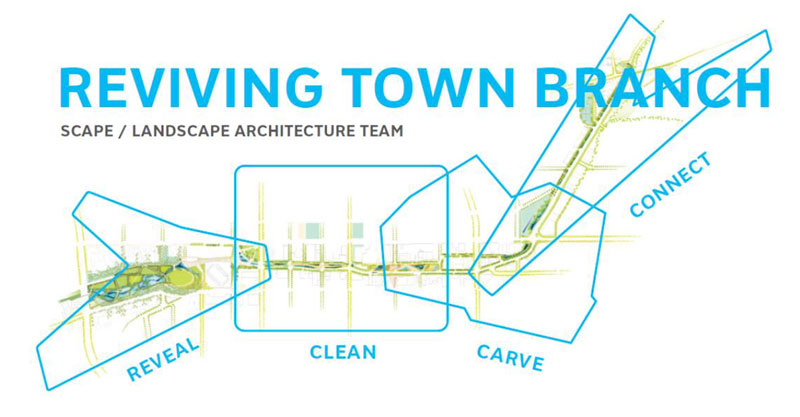

Between the Distillery District and Phoenix Park TIF districts sits the Rupp Arena Opportunity Zone, which has been test-marketing plans for $300 million and up in publicly funded construction costs.

The city has been shopping around developers for the land surrounding the downtown transit station; its most recent suitor previously filed for and then withdrew a TIF application to help fund an unrealized movie theatre project along Angliana Avenue.

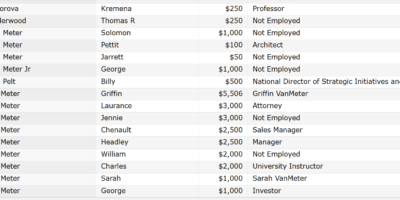

In the East End, a TIF of nearly $17 million has been granted to ProgressLex board member Phil Houlobouk, a real estate developer when not championing progressive causes, and conservative former Vice-Mayor Mike Scanlon, also a real estate developer when not impersonating Rush Limbaugh. Amazingly, the two developers have been granted tax breaks despite having no specific development plan in mind.

On the West End, former Democrat state Senator Ben Chandler and his development consortium have been green-lighted locally for another couple million in future tax commitments for Thistle Station, a sixteen story, $34 million apartment complex whose investors seriously believe that community college students are a good bet to purchase or rent one of their projected upscale apartments.

Walking the TIF Commons

In Lexington, a river runs through most of these TIF districts. Or, a submerged creek does.

The proposed Town Branch Commons, the 2.2 mile urban linear park that promises to overtake Rupp as the Mayor’s #1 civic project, will symbolically follow the city’s submerged Town Branch Creek from its (symbolic) headwaters at Third Street’s Isaac Murphy Memorial Park to its emergence at Rupp Arena. (Symbolic is an important aesthetic for the project—the creek will mostly remain submerged under two centuries of train and auto transport infrastructure.)

Whatever its public benefits—and we’ve heard everything from safely providing passage for poor black residents from the East End to their low-pay jobs at 21C, to tourism enhancement—it is best to understand the Commons as a river bed that channels our current billion dollar flood of leveraged public-private urban investment. When completed, it will touch most of the city’s Tax Increment Finance zones.

At the Commons’ symbolic headwaters, the Connect portion of the Scape Town Branch design abuts the East End TIF zone.

The Carve portion runs past a LexTran station that has been publicly bandied about for redevelopment.

Downstream, Clean drains the Phoenix Park TIF and looks admiringly across Main Street at the modern, artsy 21C TIF zone.

After emerging at a manufactured waterfall, Scape’s Reveal portion will rush past the the Rupp Arena Arts and ReDevelopment District and its projected $300 million upgrades. This Rupp District money may or may not include another proposed TIF for redeveloping the High Street parking lot that sits across from it.

Downstream from the Scape “Commons,” the creek bends into the Distillery District TIF and begins its several-mile above-ground meander away from town and into heavily subsidized horse country.

As with all manufactured river beds, the Commons will not come cheap. Though cost estimates have yet to be released, the 2.2 miles of these Commons will most certainly require an additional tens of millions of dollars in federal grants, state incentives, regional bonding capacity, stormwater funds, and other local outlays—public money that will mainly improve the land values and business evaluations of our already-subsidized fat Pauls.

And as with other important infrastructure components, you will not own these Commons. The city seems intent on separating the Town Branch linear park from the rest of our park system. As a separate entity, the Commons will receive a separate (much larger) funding stream than the amenity-starved public parks you visit every day.

And so, too, will oversight of these Commons be taken from us. As a non-park entity, the land will be governed by a separate, quasi-private, oversight board—one that, sure as the Spring floods, you can bet will be packed with empty suits intent upon, above all else, keeping their private urban interests afloat.

Part 1: “Connect/April 17, 1779“

Part 2: “Carve/2000-2010“

Part 4: “Reveal/September 28, 2011” will be updated soon.

View all four parts together at Town Branch by rheotaxis.

Some of Town Branch by rheotaxis has been revised in moving from print to online. You can find print versions of this article archived under previous issues. Town Branch by rheotaxis was published June 2013.

Leave a Reply