In this university city, it is a thinly veiled secret that the arts carry water for the region’s connected class.

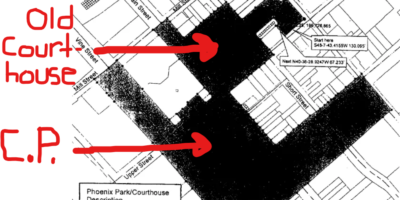

Since this site’s founding in 2009, not a single public subsidy earmarked for the wealthy has lacked the signed and stamped approval of the arts. The World Equestrian Games. Rupp Arena. CentrePointe (now CityCentre). 21C Hotel. The Summit. The Town Branch Commons. The East End’s MET. The Lexington Courthouse renovation. Art-engaged pillages, all.

In some sense, this news is hardly shocking. For millennia, art has flourished within a patronage system. To ply their trade, artists the world over have required excess wealth and circulation power–in a word, patrons–to subsidize and promote their work.

This artist-patron relationship is made thicker through the unique ways that artists circulate materially within the patronage system. They attend patron dinners and other functions, stage and participate in art hops or other artistic events heavily attended by the patron class, intermarry into or draw their own lineage from it, often live in patron neighborhoods or unlock undesirable neighborhoods for future patron settlement.

To expect these workers-of-aesthetics to potentially offend that class of people who comprise their patronage pool is…well…nonsense. It happens, sure. But not often.

Such artist-patron relationships, I would hazard, are generally true across great spans of time and territory, but they are particularly true in a modern city the size of Lexington, whose patron population is comparatively small, conservative, and ill connected to other, larger, patron markets.

In Lexington, if, say, a multi-millionaire art patron, acting as the Mayor, wanted a soul-less $300 million+ arena built, on the public dole, smack dab downtown, in an architectural style best described as neo-brutalist ark, all of this occurring in the shadow of the Great Recession–if all of that were to happen IRL–

…well, one would be unlikely to encounter many peeps of protest from one’s mid market artist class regarding said millionaire art patron’s gauche, subsidize-the-rich desires, no matter how transgressive such peeps might have been then.

Artists and the Creative Class

Like other American cities, Fayette’s modern era of artist production is notable by its twenty-first century adaptation to the Creative Class thesis, the local Ayn Randian spin on neo-liberal globalization that pits cities in a global flat-earth battle to attract the world’s most highly skilled “creative” workers.

To win the future, the Creative Class thesis argues, cities must quit building for the needs of their current citizens, the ones not creative or marketable enough to leave during the previous decades of urban de-industrialization. Instead, they should focus on building a city attractive enough to capture the footloose Creative Class and its rather homogeneous set of urban tastes and values.

Art is central to the Creative Class thesis. Along with good food and bev options, its outward community presence is, first off, deemed necessary to attract the Creative Class. A neighborhood without visible arts (music, dance, painting, etc.), the Thesis implies, is unlikely to attract top notch Creatives, who require urban neighborhoods with a specific character.

This competitive need for Creative Class art infrastructure expanded the local patron market. During the late-Aughts, what once largely consisted of snooty super-rich art collectors began to include city government, neighborhood developers and individual business-owners, entities whose main focus lie principally in branding and economic development rather than aesthetics or convention or form.

Art and Jim Gray

In Lexington, art’s community power reached its Creative Class zenith during the rise and reign of millionaire art patron Jim Gray, roughly 2008-2020. This is the era when you really started to hear those buzz phrases about art-as-business-sector, art-as-brand-identity, art-as-real-estate-improvement, the artist-as-entrepreneur, the artist-activist, and on and on and on.

City support for art during this time both deepened and broadened. Part of this would show up in the budget, as in 2013, when the city subsidized nearly 50% of Modern Art Hotel 21C’s $36 million cost to open its doors. Or in 2015, when the Mayor’s Arts and Culture administrator received a 75% boost in pay.

Some of it would show up in TIF applications and other urban development strategies. The most recent of these was Council’s 2018 decision to divert 1 percent of the amount the city borrows each year into a public art fund, an arrangement that currently nets the arts around $300,000 per annum.

Art and investor uplift

In the city’s gentrifying northside, where developer (and UK art school graduate) Griffin Van Meter was busy branding a curated group of low-income neighborhoods as the arts-focused “NoLi” district, the Creative Class thesis helped transform artists into a special protected category–like veterans or women fleeing domestic violence.

In 2015, this point was made official when the city awarded the first round of funds from its newly created Affordable Housing Trust fund. At $2 million per year, the city’s own affordable housing study would show the fund to be 90%-under-funded. Competition for Year 1 funds was fierce, which Vice Mayor Steve Kay attributed to “pent up demand.”

Despite the fierce competition and limited city funding, Van Meter’s NoLi CDC was among a handful of developers to receive affordable housing funds. Of $2.5 million in initial seed money, $320,000 in AHTF grants and low-interest loans (roughly 12%) was awarded to Van Meter’s CDC.

The city money went toward the renovation of a half-street (York Street!) of shotgun homes that NoLi had previously purchased, en-mass, through a $425,000 ArtPlace America grant. The affordable housing “niche” that the Ayn Randian-themed Luigart “Makers” Spaces were supposed to fill? Discounted, aesthetic affordable housing for artists (and other creatives)–that just by happenstance were located 200 feet from a number of Van Meter’s private developments.

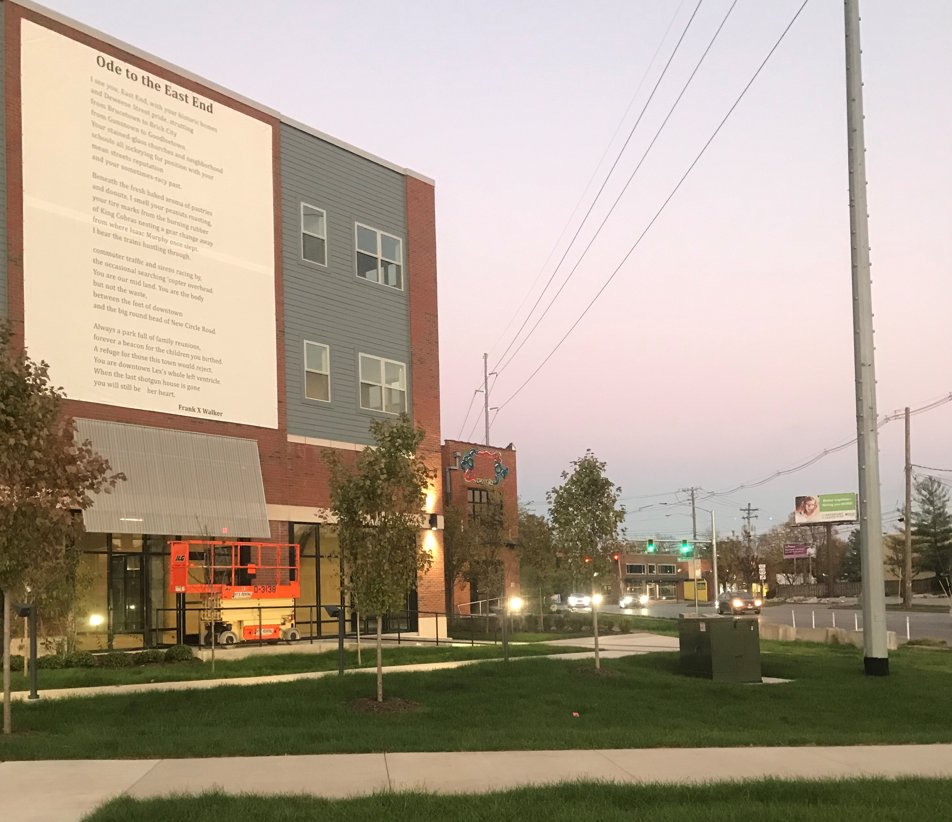

This artists-come-first idea pioneered by NoLi has since been replicated in the also-poor-and-gentrifying East End, where a planned Artist Village is among the few affordable housing options to come on-line there in the past decade.

These two emerging artist hoods are close enough to walk. From the NoLi Makers Spaces, simply follow the stylized graffiti and other art south on Limestone to the Legacy Trail at Fourth, turn left, then after a detour to the Lyric Theater at Third it’s a straight-shot to the Artist Village located behind King Cobra lounge.

Art and local power

Whether in its making or experiencing, art is an often richly rewarding, sensory-packed, life-affirming activity. As a “creator” who both makes and experiences art (and sometimes teaches it), I can testify to its power.

But art is not separate from the lived world. It circulates publicly and privately within communities, most often in the form of passable gifts not intended to feed into a booster or brand or money economy, most often by people who identify as substitute teachers or stay-at-home dads or maintenance workers. Thus it was, thus it will be.

In Lexington, as in many other Creative Class cities over the past decade, art changed when it was declared a public city good, in need of highly ranked artists to convey that good. This was inevitably a power move, one that chopped a universal and amorphous good into a series of discrete benefits for certain people to enjoy in certain hoods that had reached a certain stage of development.

What are the interests of this artist class and how are they being met? Are they more important than the interests of substitute teachers or stay-at-home dads or sate park maintenance technicians? Where are the power centers of this artist class and how do they integrate (or not) with other power centers? Who are its figure-heads and what are they saying?

These are questions that do not get much traction in our local media or advocacy groups. But they should be.

New Jawn

I read this again after just this week stumbling across an issue related to the KY Arts Council. It’s a great essay that resonated more now than it did before.

Ages ago I read C. Wright Mills “The Cultural Apparatus.” I think that it’s time for me to read it again.