Once upon a time, ages ago but not far from here, stood a long-forgotten civilization called Amarachia, bounded on the west by an scorching, infinite desert, on the north by a roaring, uncrossable river, on the east by towering, impassable mountains, and on the south by dark, impenetrable forests.

Despite its isolation, or perhaps because of it, Amarachia was a pleasant, harmonious land, where food was plentiful, work was rewarding, and children grew up strong and happy. And while Amarachia was dotted with villages, each of which offered its own unique charms, perhaps there was no more charming a village than Easannia, situated very nearly in the center of Amarachia and renowned throughout the region for its fertile farmland, rolling hills, and beautiful streams.

Life proceeded in Easannia much as anywhere else: farmers farmed, hunters hunted, weavers weaved, shopkeepers plied their wares, the blacksmith tended his forge, and the children daydreamed while teachers taught. And watching over the proceedings was the village mayor, a kindly and wise man named Ciall, who had held his office for many years and was beloved by most of the villagers.

Among the many annual celebrations and festivals the villagers held, to honor their deities and mark the passage of the seasons, none was more important than the midwinter feast, to bring one year to a close and usher in the next. On the day, the Easannians built a bonfire in the town square, watched their children perform traditional skits and farces, and sampled the offerings of the butcher and confectioner, before finally retiring to their homes for a late supper and contented sleep.

The celebration was also graced most years by the arrival of a traveling sideshow, whose caravan of carriages included the usual assortment of carnival attractions, such as sword swallowers, fire eaters, and a sleight-of-hand artist, who reliably produced coins from behind the ears of giggling tykes. But this time there was something new: the last carriage was no carriage at all, but a low platform of sorts, upon which rested an enormous round…something—the Easannians couldn’t tell what it was, as it was covered by a rough burlap drape.

The villagers each had a look at the concealed round shape as they passed, scratching their chins and quietly speculating to one another on what it might be, until finally a man—a stranger, slight of build but otherwise ordinary in appearance—emerged from one of the carriages, clambered onto the platform, and began to loosen the drape’s ties.

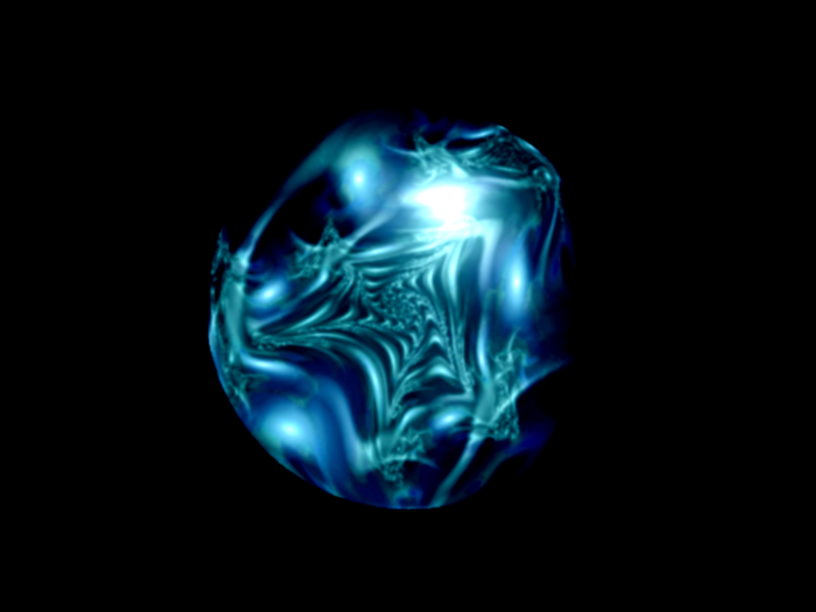

This drew a crowd. The curious Easannians circled the platform and waited to see what would be revealed. After some labor, the stranger removed the last tie and pulled the drape away, revealing a glassy orb, some six feet in diameter.

Immediately the cries went up: “What is it?” shouted one villager. “What does it do?” shouted another.

The stranger motioned for quiet. “My friends, this is a magical orb,” he replied. “It does everything. It contains within it everything you have ever sought, everything you have ever wished, everything you have ever dreamed.”

The villagers looked from the stranger to the orb and back again, muttering skeptically amongst themselves. Finally the village cripple, Bacach, spoke up: “Will it fix my leg?” he asked, pointing to his malformed limb.

“Yes it will,” answered the stranger, “and much, much more.”

Another round of general harrumphing, and the local healer pressed the stranger: “And how much does this miracle cost? And how does it work?”

“You merely need to gaze upon it, that it might manifest its power, and it will cost you nothing,” the stranger replied. “I will give it to you for free, one on condition.”

“Oh? What’s that?” the healer asked.

“That you may never give it back,” replied the stranger.

The mayor Ciall had observed the goings-on, with crossed arms and a dubious expression, from a spot near the rear of the circle. Now he was approached by several villagers: “Shall we, mayor?” one asked. “What harm might it do?” asked another.

Ciall, cautious by nature, had seen enough during his time to know to be wary of claimed miracles, but he could find no immediate objection. The orb possessed a certain beauty, glossy and gleaming as it was, and if nothing else, would serve as an interesting conversation piece, or an attraction for travelers. An odd condition, this business of not being able to return it, and he considered this for a few minutes, ignoring the entreaties of his constituents. But eventually he gave a little shrug and spoke. “I see no reason to decline the offer. Have that man place the orb in the square, in the grass west of the path. If we tire of it, we can roll it elsewhere.”

And so this was done. After some deliberation by the assembled villagers, it was decided that the cripple Bacach would look first into the orb, his need seemingly the most pressing. He limped toward the orb and fixed his gaze upon it. For a few moments he said nothing, his expression blank, but soon he became transfixed, his jaw slackening, his shoulders slumped.

The butcher cried, “what is it, man? What is it that you see?”

Bacach, his voice near a whisper, answered, “I see…I see…everything. Come, look upon it too. There’s room for everyone…” And with that he trailed off into silence.

One by one, the villagers all gathered around the orb, stared into it, and stayed there, motionless. Among them was a young farmhand named Taithi. Peering over the blacksmith’s shoulder, he’d looked into the orb, seen nothing at first, but then had found himself confronted with a reflection of his own visage—but changed, transformed: in this reflection he was much more handsome, taller, and somehow smarter, more assured. He was, in this vision, everything he’d ever wanted to be.

Within a few moments he found that he could inhabit this reflection, control it, live within it. And he could move, travel, transport himself to far off lands in an instant, where he met queens and emperors, slayed beasts and monsters with nary a scratch upon him, and seduced beautiful princesses. He constructed for himself a tremendous palace, then razed it and constructed another in its place. He was omnipotent; he was a god.

All around him the other Easannians were living their own dreams and aspirations; a noiseless crowd of hundreds now surrounded the orb. In fact the entire village had given themselves over to their visions, with the exception of the mayor Ciall and the three members of the village council: Malai, a stoneworker by trade; Dana, a carpenter, and Tinn, the bookkeeper. For as the rest of the villagers had begun to gather around the orb, the mayor and his council had retired to the council chambers to conduct some routine year-end business and accounting.

As the meeting wore on, it was Malai who first noticed the strange silence from the village square. He moved to halt the proceedings, that they might investigate, a motion to which the mayor and councilors readily agreed. And so the quartet made for the square, where they found the entire populace rapt and unresponsive. No amount of pleading or cajoling could break the villagers’ attentions, nor would any be physically disturbed. Dana went so far as to pick up one of the children and attempt to remove her from the scene, but the lass began shrieking and convulsing so violently that the councilor feared for her well-being and returned her to her spot, where she once more fell calm and silent.

“This is not good,” said Ciall, and Tinn murmured his assent. But Malai, a scheming sort who had long resented the mayor and his own life of labor, saw opportunity.

“Ciall,” Malai said. “You serve at the pleasure of the people, do you not?”

“I do,” replied Ciall.

“But now your people seem unable to tear themselves away from this new master, do they not?”

“They do.” Ciall grew uneasy, for he knew of Malai’s hunger for power and riches.

“And if you were removed from the people’s service, it hardly seems likely that they would protest, no?” Malai had begun to smile, ever so slightly. Meanwhile Dana, who’d already seen which way the wind was blowing, had moved to Malai’s side.

Ciall’s hand went to the dagger on his belt. “If you mean me harm, have your way now, and cease your insinuations.”

But the fact was that Ciall was already quite an old man, and no match in combat for the younger, stronger Malai. Perhaps Tinn would aid him, but Tinn was timid of heart, and…

“Tinn,” began Malai, “please remove Ciall’s dagger from his possession.” Tinn looked ashen, ashamed, but as he saw the intensity of Malai’s expression, and behind him Dana, slowly nodding, he saw no other option but to obey.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered to Ciall, taking the dagger from Ciall’s unresisting fingers. “I have no choice.”

And so Ciall was bound and led to the jail, while Malai conspired with Dana to ransack the wealth of the village and live a lordly life in warmer climes.

Outside, darkness fell and the air grew terribly cold, but still the Easannians remained, glued to the orb. Frost gathered on their fingers and faces, and as the night passed many began to crumple to the ground, frozen, dead. As the sun rose again the next morning, merely half the villagers remained standing, still transfixed by the orb, unaware of the growing horror around them. And so that day passed as well, and that still colder night. By the wee hours, only Taithi was still upright, and as the very first hint of daybreak lightened the sky, he too collapsed.

Sabhail saw him fall. She was Easannian herself, but had spent the past week tending to an ailing relative in a nearby village. The relative had finally died, and in her grief she’d decided to ride home through the night, heavily cloaked against the cold, rather than waiting until dawn. Now, her face wind-burned and tear-stained, she came upon the scene of what seemed to be a massacre, centered on a gigantic glass sphere.

She dismounted and rushed to Taithi, who was prostrate and entering his final throes. Kneeling and wrapping her cloak around him, she held his face and tried to bring him to. “Taithi,” she said. “Taithi, what’s happened here?” Getting no response, she lay beside him and held him tightly, trying to impart her warmth to his frozen frame. After some time and her repeated entreaties, Taithi stirred, just a bit.

“The orb,” he croaked. “I must see it. I must see it.”

Whatever the orb was, Sabhail wanted nothing to do with it, and was suddenly overcome by the feeling that she wanted to get as far away from it as possible. She replied, “you’ll do no such thing,” and began to lift Taithi to his feet. He was unable to stand, but she found the strength to bear his weight, and with considerable effort she heaved his limp frame across her steed’s saddle. She then led the horse and its insensate rider away from the square, out of the village, and toward a secluded glade by a stream-bottom, where once she’d played as a child.

Once there, Sabhail set about making a fire, and with that done, she built a lean-to with branches and riding blankets. She pulled Taithi from the saddle and installed him within her hastily built shelter, as near the fire as she could without catching his clothes alight. Slowly, he came around, and when he seemed able to swallow, she gave him water and some bread she’d carried in her saddlebags.

His senses returned to him, mostly, he began to speak again. “I must go back. I must see it again.”

“See what? What did you see?” asked Sabhail.

“I saw…everything. Everything there is to see. Everything there is to feel. Everything there is.”

The dawn had broken now, and the light of the low sun glanced off the ice-covered stones of the trickling brook before them. Sabhail asked him, “Did you see this sun rise, on this morning, warming those stones so that they seem to glow?”

Taithi hesitated, thinking. “No, I don’t think I did. I guess not.”

She persisted. “Did you feel the warmth of this fire, on this morning, thawing you that you may move and speak once more?”

He shook his head. “No, I did not.”

She pointed to the brook. “Did you hear the murmur of this stream, breaking the quiet of this morning?”

“No.”

She pointed to the tall firs at the edges of the glade. “Did you smell these trees, rich and sweet, as the sun warms their needles?”

“No.”

Leaning toward him, she kissed him gently, letting her lips linger. Withdrawing, she asked him, “did you taste my tears on your lips, having lost and then lost again?”

“I did not before.”

“Then you did not see everything.”

They stayed there, by the fire, saying nothing, until they felt it was time to go. Then they rose, mounted, and rode east into the rising sun.

Leave a Reply