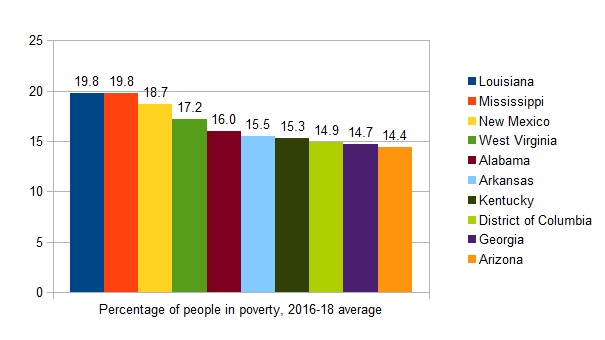

Kentucky Commissioner of Education Wayne Lewis knows the research is clear. In school achievement measures, districts with high levels of poverty struggle. Comparatively wealthy districts succeed. The correlation is strong and well documented.

In an editorial he distributed earlier this year, Lewis laid out the facts:

[T]he most notable of the education challenges we continue to face is socioeconomic and racial achievement gaps…in [one district] only 41 percent of economically disadvantaged elementary school students scored proficient or higher in reading, compared to 69 percent of their non-economically disadvantaged peers who scored at the proficient level or higher. The gaps in reading remain constant at the middle and high school levels. In math, only 36 percent of economically disadvantaged elementary school students scored proficient or higher, compared to 66 percent of their non-economically disadvantaged peers. The mathematics gaps widen at the middle and high school levels.

Yes, that’s how it works: rich and middle-class kids score better than poor kids. And since non-whites are more likely to be economically disadvantaged than whites, they’re more likely to show lower levels of academic achievement. This is pretty simple stuff. Here’s Lewis again:

There is no doubt that socioeconomic and racial achievement gaps are a function of home, community and school factors, and the elimination of gaps will require that challenges in each of these areas are addressed.

Right, then: let’s close the gap between rich and poor, bring more kids—white and non-white alike—out of poverty and into the middle class, and we’ll see those achievement measures rise. That’s a good plan.

Well, you’d think so, but Lewis doesn’t want to commit to reducing poverty. Instead, he hedges:

Research shows that even when no variable is changed except teacher behavior and quality of instruction, academic and behavioral outcomes for students can change… when students who started the academic year behind grade level had access to stronger instruction, they closed gaps with their peers by six months.

Effective instruction matters. Exposure to grade level content matters. High expectations for all students regardless of their background matters.

And that’s been Lewis’s modus operandi during his tenure as ed commish: acknowledge publicly that structural economic inequality has a profound effect on educational achievement, then proceed to shift the focus to the presumed failings of Kentucky’s teachers. We’ve seen him do this repeatedly.

This past summer, as news outlets reported on the growing shortage of qualified teachers statewide, and especially in rural areas, Lewis responded by presenting a teacher-recruitment/retention campaign involving Teach for America and simpler paths to teacher certification.

Good ideas, surely. But Lewis had nothing to say about the desperate need to reduce rates of both urban and rural poverty in Kentucky, and nothing to condemn Governor Matt Bevin’s relentless, vicious attacks on teachers. Not a word.

Then a month ago, while responding to criticisms of the new five-star school rating system, he did it again. School improvement depends on “nothing but what we provide to [children] when they come to school.” Not poverty, not adequate classroom funding, and again, not a governor who on separate occasions blamed teachers for hypothetical child abuse and an accidental shooting. Once more, it’s all on the teachers. For Lewis, they’re just not doing a good enough job.

In response to Lewis’s strange tunnel vision, this past April special-ed teacher and administrator Alison Stone penned an open letter in the Louisville Courier-Journal, in which she described quite clearly why sensible, qualified people would be foolish to want to teach in Kentucky these days. In the letter she describes working in overcrowded, underfunded classrooms full of children from terrible socioeconomic circumstances: she and her colleagues across the state are fighting a losing battle against the consequences of poverty, all while being attacked by a governor who seemingly despises them.

Yet Lewis insists he can simply find better teachers, who will somehow cure Kentucky’s educational ills, without explaining why on earth any potential teachers would want to work in Kentucky in the first place. Or if they did, why they’d settle for anything less than, for instance, a high-performing middle school in a rich district, maybe here in our affluent enclave of Lexington. Does he seriously mean to suggest the best and brightest education majors would have any interest in working in Kentucky’s lowest-performing districts, such as inner-city Louisville or rural Breathitt County? Why would they, given his insistence that pervasive economic distress is no excuse for poor academic performance? When the next year’s scores came in, and improvement was marginal or non-existent, these new teachers would find themselves under attack. Why on earth?

Put simply, Lewis just isn’t interested in addressing, with any depth or seriousness, poverty’s effects on educational achievement, and I can only assume the reason is political. Demanding that Kentucky’s legislative and executive branches work on the problem of poverty in our state, as a prerequisite to improving educational achievement, would contradict the core right-wing narrative that poverty is the result of a moral failing of the poor.

This is Matt Bevin’s position, certainly, nowhere better demonstrated by his absurd, widely mocked plan to schedule “prayer walks” to curb violent crime in Louisville. In that bit of offensive nonsense, our governor assigned blame for the violence in that city—violence which any first-year sociology student knows full well is associated with poverty and the absence of economic opportunity and social mobility—to residents’ failures to get right with God. It was a particularly sickening application of the prosperity gospel, of the pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps myth, but at least it made clear how Bevin thinks: if you’re poor, it’s your own damned fault. God favors the well-to-do.

Wayne Lewis, a Bevin appointee (and apparent devotee of the increasingly discredited Michelle Rhee), appears to have done nothing more than appropriate this narrative for the educational sphere: we can’t blame poverty, because poverty is the fault of the poor. But we can’t blame the kids, because their poverty isn’t (yet) their fault. So instead we must blame the teachers. If only they worked harder, if only they were better at their jobs, then scores would rise, employers would flock to Kentucky to take advantage of the smart, agile workforce, and we would all bask in the glory of our leaders’ great foresight and wisdom.

But it doesn’t work like that. It has never worked like that. Wealth, or its absence, dictates academic achievement to a massive extent, and as such, the socioeconomic gaps that Lewis reluctantly acknowledges must come first. In only the past week we’ve learned that teachers in Kentucky are fleeing the profession in record numbers, while national assessment scores are, once again, disheartening. Lewis calls this an “academic emergency.” I agree. But given his insistence on clinging to failing, ideologically driven models of educational improvement, it doesn’t seem as though he’s the right person to respond to it.

Leave a Reply