By Danny Mayer

John Hartford is one among a generation of artists—Kentuckians Hunter S. Thompson, Ed McClanahan, and Gurney Norman among them—who came of age during the 1950s, soaked in the cultural and social upheavals of the 1960s in hippy-dippy California as relative (and relatively old) unknowns, and then proceeded, in the early Seventies, to produce some of the most thoroughly saturated “Sixties” works one could ever hope to encounter.

It wasn’t until 1971 that Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas appeared in the iconic ’60s startup Rolling Stone magazine. That same year McClanahan’s “Greatful Dead I Have Known” hit the Playboy stands. Ditto for Norman’s Divine Right’s Trip, subtitled A novel of the counterculture, which began to run serially in the back-to-the-earth publication The Whole Earth Catalog.

For the song and dance man John Hartford, 1971 brought the release of Aereo-Plain, an album best described as a perfect expression of counter-cultural bluegrass music. The sound was a distillation of Hartford’s two different decades as a musician. There was the 1950s teen years spent listening to late night country radio, playing old time fiddle and banjo music, and dreaming about the Mississippi River. And then there was the Sixties, spent as a radio DJ in Nashville, later as a witty but otherwise undistinguished California-type folkie with a banjo, and later still as an accomplished session player for albums like the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

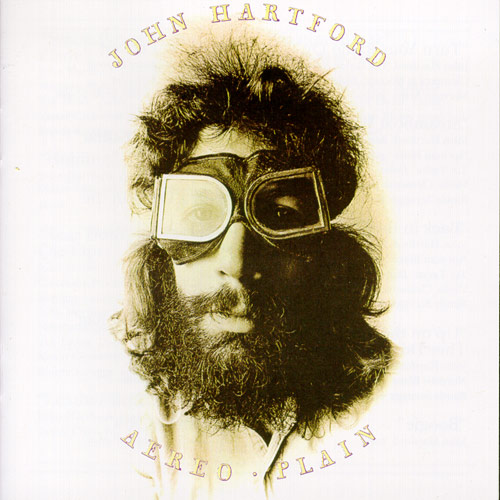

In Aereo-Plain in 1971, Hartford synthesized those two decade pulls. The new and the old matched. Critics cite the record as ground zero for the newgrasss movement with good reason. It fused the more conservative old school bluegrass traditions of Hartford’s youth to the feel-hippy adventure-seeking wit and punch he encountered as a studio musician playing at the height of the 1960s acid rock craze. Even his Aereo-Plain band, new-school long-hairs Norman Blake and Randy Scruggs and old-school short-hairs Vassar Clements and Tut Taylor, split generationally down the middle. Jim Morrison talked about doors; and here was Hartford, the old hippie with the old-timey goggles, a veritable time and sound portal.

Moving east, growing young

Stylistically, Aereo-Plain is more Divine Right’s Trip than Fear and Loathing. The album comes cloaked in the counterculture and youthful hippie vigor of the era, but like Divine Right’s Trip things seem mostly to veer away from the trendy, tapped out spots in favor of the country. The cover features a head shot of a long-haired, bearded John Hartford, a pair of old-timey plane goggles swallowing his cheeks and forehead. The songs are peopled with a love generation dispersed from the California hippy ghettoes to the heartlands. Roving hippies stumble upon the hills and good friends pledge each other their theoretical marijuana stashes. Even the playfully nostalgic “Back in the Goodle Days” takes place around a garbage dump where joints, wine and “anything good from on down the line” circulate freely.

But still, geographically, things seem closer to the Monterey found on the Kentucky River than the one located on the Pacific Coast. As with Gurney Norman, the aging Hartford would steadily move away from California hippiedom without fully leaving it. Soon after finishing his landmark album, the singer would retire, become a river boat pilot and take to plying the Cumberland and the Illinois and the Tennessee and the Mississippi Rivers with a boat full of hippies for a crew. When he returned to recording five years later with Mark Twang, a solo work in the truest sense (he played everything, with no overdubs), Hartford was a visually changed bard. Lyrically, the grand narratives of the 1960s had begun giving way to the small wonders of a timeless life spent on the river. In Mark Twang (coincidentally, coming out a year before Norman’s 1977 Kinfolks), aereo-planes start getting traded in for river boats and gum tree canoes. Instead of going up on the hill, to do do the boogie,things start to downshift toward the river banks, all the better to watch the river roll by (occasionally naked–but only because it’s real hot…he swears…and winks).

By the time I first saw him, a couple years before his death in the late 1990s in rural West Georgia at a structure calling itself Hoofers Restaurant and Gospel Barn, Hartford’s visage had changed considerably from his Aereo-Plain days. Now with short hair, shaved and bespectled, he stood stooped over his fiddle, a bowler hat in place of his flight goggles. Surrounding him, a quartet of young musicians played old time string music into a single shared microphone. His voice was weathered and weak, the result I was told later of several decades with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He clogged twice, briefly before he tired, and drew much applause both times. Steam Powered Aereo-Plane suffered somewhat, but songs like Cross Eyed Child (an oral history of Bill Monroe set to music), Jenny on the Railroad, and Quail is a Pretty Bird scorched. Watching him play fiddle was like watching current flow.

Afterwards, my friend Tim and I shuffled up to meet him after sifting through the discounted analog at his merch table. I’m not good at such things, so I stood by silent as Tim told John he lived in a basement. John looked up at the two of us and replied, “Are you all brothers?”

Turn your radio on! Hartford on WRFL, Al’s Bar

Turn your radio on

and listen to the music in the air

In addition to being a crack fiddler, picker and riverboat pilot, John Hartford also had a voice for radio. Having worked as a DJ early in his career, Hartford penned and covered a variety of radio-themed songs. On Tuesday, November 1, beginning at 8:30 PM Danny Mayer will play two half-hour sets of John Hartford music on WRFL’s Flying Kites at Night program as a celebration of public radio and public ways of communication. You are invited to Al’s Bar for open-mike night, where the second set of the John Hartford Radio Hour, beginning at 9:00 P.M. sharp, will be played live over the loud speakers. Admission is free. The event is also part of our North of Center fundraiser, so expect mild and friendly panhandling, and a merch table.

Drop by Al’s and have some fun, tune in to WRFL (88.1 in the Lexington area), or log into the WRFL homepage to listen in live on the show. Or organize your own Turn your radio on! party and contact Danny Mayer at Mayer.Danny@gmail.com so he can give you a solidarity shout-out on the radio.

This version has been expanded from the original print version. Original version can be seen on website archives as a pdf.

Arjun Kanuri

It’s going to be end of mine day, but before end I am reading this fantastic piece of writing to improve my know-how.

Donnie Hoffman

John was NOT from Kentucky, but from Missouri. -Webster Groves and then University City MISSOURI. The Harfords (the T was added when John was at RCA) were nice quiet folks. His dad was a distinguished doctor at Washington University, -John’s alma mater and mine as well. For high school, John went to John Burroughs private school, as my great Friend Jim Davidson would constantly remind me. When John passed, Jim wrote a wonderful, heart felt obituary for the John Burroughs newspaper. I still have this great piece cut out in my copy of Aereo-Plain. It reminds me that I am not the only one in permanent mourning. I have a rare blood disease so I never thought I’d ever have to see John and many other people die -but you never know how things are gonna work out. Dear Lord, living longer is a curse.

My teenage mates and I idolized John Harford. He was a good 10 years older than us and we went ape-shit when “Aereo-Plain” came out. After all these years I cannot think of a better adjective than “ape-shit”. Some things stick with you through life. That record was so powerful that it changed our DNA. There is no way to underestimate Aereo-Plain’s affect on us kids. My friends and I spent many a night round a fire, next to next to The River passing the bottle (“and what ever came down”) underneath the black star-glutted southern Ozark sky. We listened to The Record on my friend Bill’s cassette player that we rigged up to his 1965 Fury. To us, “Aereo-Plain”, The River and that Ozark sky was all ours. -Our private heritage and rite of passage with John Harford showing us the way. Now it seems more like heaven. -The odors & sounds of the woods with Whippoorwill singing backup. I cannot imagine better Heaven.

When I got a little older and starting playing music, I got to meet John backstage a few times. A quiet guy, but real nice. He suffered my stuttering and dumb questions well. And I also have a few great backstage John Hartford stories that some day I should probably write up. Maybe after a little more time passes. For me, I am still in intense mourning. The last of my youth has died. There is no more John Harford with that Radio John voice down low that made you listen. Lord, I miss John Harford.

Donnie Hoffman

Carolyn Harford

Thank you for these memories Donnie!