On the Fayette commons, part 3

By Danny Mayer

Don’t look to me for virtue, for high-minded feats or elevated speech that flows in a stream of lustrous silver—when cutting is my nature, meandering my path. Find me instead lowdown, landscape in tow as I take the way of least resistance, draining the uplands, purging the slopes.

From “The river issues a statement regarding its watery ethos,” by Richard Taylor

The Scape/Landscape Architecture design plan entitled “Reviving Town Branch” presents a compelling vision for a linear downtown urban park. The plan divides the Lexington, Kentucky, Town Branch watershed into four design phase/areas: Reveal (Rupp Arena), Clean (Vine Street to CentrePointe), Carve (CentrePoint to Thoroughbread Park), and Connect (the lower East End to Isaac Murphy Park).

The Scape map, like all maps of the area, lends itself to a certain reading. The stream’s textual and cartographic flow, Reveal/Clean/Carve/Connect, makes movement from left to right, upstream, seem natural. Reading it, one might assume that Town Branch’s source flows from a revealed Rupp, passes through a cleansed then carved downtown, and thence arrives, trickled-down rainfall depending, to a textually disconnected Isaac Murphy park.

To get Town Branch, or at least to get a different Town Branch, one that takes hydrology and history as its compass axes, it seems one must read the map backwards: from right to left, downstream, East End headwaters to Distillery District emergence, connection to carve, and thence to clean and reveal. What follows is a stab at that downhill backwards reading, what I’ve been calling (with many thanks to High Bridge river rat Wes Houp) “Town Branch by rheotaxis.” ~ d

Connect/April 17, 1779

Kentucke, once bloody ground, hunting Eden for native tongues apologetically eliminating buffalo for sustenance. Not sport or profit or pleasure.

–Frank X Walker

In the spring of ‘79, a pack of colonialists led by Colonel Robert Patterson exited their fort at Harrod’s Town, a bleak wooden western outpost incised into the recently formed Kentucky County of post-colonial Virginia, with orders to establish a garrison inside the vast canelands that temptingly rolled north off the palisades that lined the far banks of the Kentucky River.

For the Pennsylvania men exiting Fort Harrod, as for the North Carolinians immigrating to Fort Boonesborough and Saint Asaphs, dominion over the rich north land lying between the Kentucky and Ohio Rivers had proven particularly difficult. Shawnee, Mingo, Miami, and a clutch of other area residents had for some time made homes along several of the south-running Ohio River tributaries that debauched into La Belle Riviere from the north. These groups still claimed the commonwealth as a commonland, a hunting and commerce grounds held in usufruct by Indian, some French, and the odd colonial shareholder. Encroachment on the commons by tree-hacking, game-destroying, compass-wielding Pennsylvanians, Virginians, and North Carolinians had met some resistance. For the half decade preceding Patterson’s historic northern incursion, a cartographic truce had emerged: to the south of the protective girdle of the Kentucky River, colonists; to the north of the Ohio, Indians; and in between, the canelands.

This is not to say the frontier Colonel was unfamiliar with the territory. He and many of his 25-man party had spent considerable time over the previous five years across the river surveying what, even in April 1779, was still unstable land. Most had entered Kentucky illegally under a Crown rule that since 1769 had banned development into the western frontier, and they had come in the employment of large corporate land companies who, in claiming tens of thousands of acres for themselves, had illegally negotiated partial and conflicting treaties with the commonwealth’s many tribal claimants.

This is not to say the frontier Colonel was unfamiliar with the territory. He and many of his 25-man party had spent considerable time over the previous five years across the river surveying what, even in April 1779, was still unstable land. Most had entered Kentucky illegally under a Crown rule that since 1769 had banned development into the western frontier, and they had come in the employment of large corporate land companies who, in claiming tens of thousands of acres for themselves, had illegally negotiated partial and conflicting treaties with the commonwealth’s many tribal claimants.

But as Patterson rode away from Fort Harrod that April, he did so under the rule of an altogether different government. This one was located closer, in the rebel colony of Virginia, and within the month it would issue a new land law claiming for itself sovereign title over the land of Kentucky, a legal declaration that created for the coastal American colony an added income source to help fund its war with the British. The law would create a crude and inefficient mechanism for legalizing land claims made the previous decade on the Kentucky frontier. The land law represented a window of opportunity for the small population of retired militia, squatters, mad farmers, game hunters, and adventurous second sons of European wealth who had entered the commonlands between 1769 and 1779. It allowed them all to log 400-acre claims upon the territory so long as they could provide a legitimate survey and evidence of first improvement. It would also grant them access to another 1000 acres of contiguous land, sold like the original allotments at dirt-rate government prices. (Any land left unclaimed by a set date would revert to Virginia, which would sell it in hunks to individuals or be used as pension for soldiers fighting the revolution.)

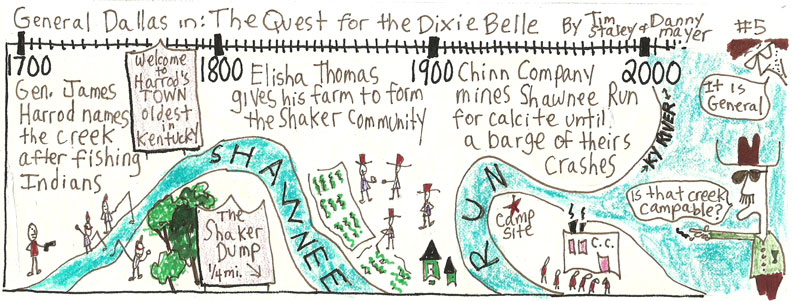

Perhaps sensing the coming change, after Patterson’s party crossed the river, most likely at calcite-rich Shawnee Run, it made haste to an area surrounding the headwaters of a small fork in the greater Elkhorn River watershed in present day Fayette County, on ambiguous territory close-by land claims previously registered by the Colonel and some others, including William McConnell, John Maxwell, John Todd, and James Masterson.

Patterson ordered encampment two miles east of the McConnell claim at a series of springs “whose grateful waters,” the dependably florid local historian G.W. Ranck records in 1872, “in an unusual volume emptied into a stream nearby, whose green banks were gemmed with the brightest flowers.” The next morning, April 17, the men set to improving the immediate area. In defense of red men, wild panthers, and cold weather, they hacked down bur oak, blue ash, and pignut. The astors and trillium were sacrificed without notice to dragged logs, pastured hogs, a few channeled pikes. Within the week, the local historian Lewis Collins would observe in 1848, the men had constructed “a solitary blockhouse, with some adjacent defences, the forlorn hope of advancing civilization.”

Soon after Lexington’s founding, a group of settlers with an eye for the main chance who hailed from the fort at Boonesborough, North Carolinians mostly, would cut a second outpost in the wilderness to the north of Lexington. This station, Bryan’s Station, along with Strode’s near present-day Winchester, would buttress Fort Lexington from native attacks. “Though the discipline about the fort is said never to have been very rigid, nor the stockade kept in strict order,” Ranck writes of Lexington’s foundational settlement, it “escaped any serious danger from Indian attack.” Its new residents would spend the historically cold winter of 1779-80—a winter that would find General George Washington and his army of barefooted rebels plotting a mountain range away at Valley Forge, and, considerably closer, Dan’l and Rebecca Boone sugaring together along the bottoms of the Fayette County creek currently bearing their name—flaccidly commanding the fort’s springs from Indian attacks, hunting, and otherwise asserting territorial weight.

Ultimately the new land law would lead, Collins argues in Historical Sketches of Kentucky, to “a flood of immigration” and a radical transformation of the area. “The hunters of the elk and buffalo were now succeeded by the more ravenous hunters of land; in the pursuit, they fearlessly braved the hatchet of the Indian and the privations of the forest. The surveyor’s chain and compass were seen in the woods as frequently as the rifle; and during the years 1779-80-81, the great and all-absorbing object in Kentucky was to enter, survey, and obtain a patent, for the richest sections of land.”

“Indian hostilities were rife during the whole of this period,” Collins concludes, “but these only formed episodes in the great drama.”

Chief among its early peers, Lexington prospered from the great drama. The fort fast became a crossroads for south-scurrying Pennsylvanians floating down the Ohio, and for north-tromping Virginians angling through the Cumberland Gap. Within two years of its founding as in unmarked territory, May 6, 1781, Lexington was granted a city charter by the powers vested in the fledgling state of Virginia. From a handful of shingled private land-claims, the Charter carved 640 public acres for city streets and a number of city lots for resale to immigrants. Seven men, Robert Patterson, John Todd, and William McConnell included, were granted each fee simple rights to an additional 70 acres of land immediately surrounding the Lexington 640.

In what might go down as the second largest all-time bummer deal in county history, the Charter traded away an entire county of commonlands in exchange for civilization, roads, and a two acre commons located just outside the original fort walls.

The Lexington springs, meanwhile, didn’t fare much better. Once free-flowing, they were immediately damned and fortified as a first act of Lexington development. As the settlement grew and the fort was removed, Ranck writes, “the [fort] spring was deepened and walled up for the benefit of the whole town, a large tank for horses was made to receive its surplus water, and for many years, under the familiar name, ‘the public spring,’ it was known far and wide.” Eventually, though, like the rest of the springs in the area, building construction along Main Street swallowed it, though presumably, under even those private constructions, the once public spring flows still.

Carve/2000-2010

The root issue is land.

–Max Rameau

Writing in 1964, the sociologist Ruth Glass created the word “gentrification” to define what she saw at play in many of London’s working class neighborhoods. “One by one,” she noted, they “have been invaded by the middle classes—upper and lower.” What Glass saw should by now be familiar. Old Victorian homes long since broken into multiple blue collar domiciles begin to get restored to single family. Blocks of shabby homes transform into pretty domiciles with fresh paint. New businesses arrive weekly to serve the needs of the newly arrived residents. “Once this process of ‘gentrification’ starts in a district,” Glass observed of these London neighborhoods, “it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working-class occupiers are displaced and the whole social character of the district is changed.”

In many ways, Glass was writing in 1964 about a topic of marginal interest to an American audience. Though gentrification did occur in select areas of large cities as far back as the 1950s, the general half-century trend that followed World War II here in the non-bombed-out United States was that of suburbanization. The middle class was leaving the city for the unclaimed spaces of newly ripped farmlands, and they were taking their public and private development monies and any other side-capital with them. Along with an aging infrastructure, the working class and poor were what remained behind. Only within the last two decades has this outward trend reversed, with American and global money, its sitcoms, media space, and middle classes now returning to the urban and near-urban core.

One of the first to note this switch was the academic Neil Smith, whose 1996 collection The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city connects gentrification to the process of eighteenth and nineteenth century frontier land-claiming. For Smith, a geographer by trade whose first-hand observations of the gentrification of New York’s Lower East Side provide the framework for his book, both the present urban frontier and the past “western” frontier are economic and cultural things.

Economically, he argues, the olden frontier “was extended westward less by individual pioneers, homesteaders, rugged individualists, than by banks, railways, the state and other collective sources of capital,” a process mirrored on the urban gentrification frontier, where “banks, real estate developers, small-scale and large-scale lenders, retail corporations, [and] the state” all generally precede or complement most individual urban pioneering.

Culturally, Smith argues that both frontiers help forge a larger “national spirit” expressed as “boosterism.” Where the Indian frontier once allowed men a place to remake themselves anew and a nation to wrap itself in do-gooder mythology, the urban pioneer now utilizes “the [optimistic] language of revitalization, recycling, upgrading and renaissance” that is designed to uplift the spirits (and public coffers) of the pioneer’s home city. “The idea of urban pioneers,” he wrote, “is as insulting applied to contemporary cities as the original idea of pioneers in the US West. Now, as then, it implies that no one lives in the areas being pioneered–no one worthy of notice, at least.”

More recently, Max Rameau, lead organizer of the Miami-based group Take Back the Land, has added a specifically racialized component to the process of gentrification. In the fall of 2006, Rameau’s group seized control of a publicly owned vacant lot and, for six months, constructed what became the Umoja Village Shantytown, a community-based encampment for homeless residents. Like Smith, Rameau recognized the gentrifying work of banks, city and state governments, real estate developers, and the like.

But he placed the thrust of the gentrification process within the strictly racialized narrative of civil rights. “In many ways,” he writes in Take Back the Land: Land, Gentrification & the Umoja Village Shantytown, “gentrification in the 2000s is the functional equivalent of segregation in the 1950s and 60s…In both instances, rich whites make money off of the backs of poor blacks; the government is used to enforce the geopolitical objectives of the larger white community, particularly the wealthier whites who covet the inexpensive and strategically situated black neighborhoods; and black families have little real power to determine, on their own, where they will live. In segregation, we were forced into one area and in gentrification, we are forced out of one area.”

Since 1790, the United States Federal Government has issued a national census of inhabitants living within its territories. Though its numbers make no formal argument for forced and free movement, its data does capture statistical snapshots of stories in motion at all levels of society.

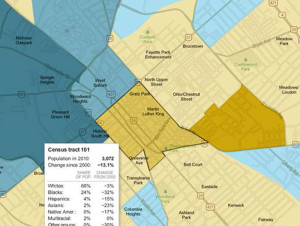

In Lexington, one story that a comparison of the 2000 and 2010 census tells is statistically similar to that of Remeau and Smith. During the first decade of the millennium, the city’s downtown core, census tract 101 running between Maxwell and Third Streets from Thoroughbred Park to Broadway, lost 13.1 percent of its population. While it is true that the Booze District west of Broadway, census tract 102, experienced a 15 percent increase in population, in aggregate the downtown core has still leaked people during its proclaimed boom times. To the core’s immediate north, three census tracts (2, 3 and 4) that span from Newtown Pike to Winchester Road reveal a similar emigration of residents. These booming urban north-side tracts—Jefferson Street (tract 2, 6.9 percent decrease), North Limestone (#3, losing 5.5 percent), and the East End (#4, down 47 percent)—have all lost population. To a lesser extent, the same holds for southern core neighborhoods Chevy Chase (tracts #5 and #6, down 6 percent and 4.6 percent, respectively) and Woodland (tracts 801 and 802), off close to 2.5 percent from its 2000 census population.

The only areas contiguous to the city core showing growth appear in the west end. In the northwest, a largely hispanic influx (and subsequent white flight) around Georgetown Street have transformed tract 11 (11 percent growth) into one of only three majority black tracts. (How many times does one hear city leaders tout this area as symbol of multicultural Lexington success?) At the other end, to the southwest, the undergraduate growth of lily-white UK has stimulated the development of a supra-majority white tract (#9) along the South Broadway corridor.

Sitting between these two west-end growth areas is the tract containing the Distillery District/Town Branch Trail, a demographic mixed bag I’ve taken to calling Booze Branch. This tract, tract 1, experienced 35 percent growth, yet at 1,500 urban people it is still so under-populated that its density (a paltry 900 humans/square mile) more closely resembles horse country (census tract 3701, 109.5 people per square mile) and sparsely covered suburban boom space Jacobson Park (#3913, 1808.7, mostly white) than the 2,500-7,000 people/mile density that stands as the norm throughout most of the living city.

A closer look at the census does locate demographic growth trends—winners and losers, as it were. Downtown, things track Town Branch.

Headwaters: After closure and redevelopment of the Bluegrass Aspendale housing projects in the middle 2000s, nearly half of that tract’s population exited during the decade of urban renaissance that city leaders have openly celebrated several blocks away downtown. The East End also experienced a precipitous 61 percent drop in black population.

Town Branch northern tributaries: 19 percent of the black population left in my MLK neighborhood; 17 percent less blacks now live along the Broadway/Jefferson Street corridor.

Town Branch mainstem: 32 percent of the black population left downtown census tract 101.

What has been visible in Lexington’s celebrated urban renaissance, whitey, my demographic, have thus far achieved demographic victory by attrition. During the previous decade of population decline in both the city core and most contiguous neighborhoods, we emerged 10 percent stronger in MLK; we broke even along Jefferson; and we only experienced a 3 percent net loss—by far the smallest among all demographics—inside the hollowing central downtown core.

Clean/February 2009

Reveal, Clean, Carve, Connect is a strategy that ties the nuances of Lexington’s rich substrata to development potentials on its surface.

–From Reviving Town Branch, Scape/Landscape Architecture Team

In February, 2009, the Kentucky Economic Development Finance Authority (KEDFA) delivered preliminary approval for the creation of two Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts in downtown Lexington: the 14.25 acre Phoenix Park/Courthouse development and the 25 acre Distillery District. Combined, the two developments projected to cost their developers $490 million to complete, of which the city and state had committed to rebate up to $135 million—or about $3.4 million per downtown acre.

The rebate would come in the form of “tax increments,” future tax breaks amounting to the difference between what an area generates in “today’s” taxes and what taxes it projects to generate at some point in the future. In both the Phoenix Park and Distillery District TIF districts, developers could be expected to recoup up to 80% of future increments for any property, sales, and income taxes that could conceivably be connected to their sites.

According to KDFA projections, the two developers could expect an average annual combined local and state tax rebate of nearly $7 million dollars a year.

For twenty years. (Thirty for the Phoenix Park TIF.)

Welfare for rich people

Llike many recent financial products, TIF seems designed to project obfuscation. It is best to imagine TIF on a personal level.

Boiled down, your tax increment represents the difference between what you pay now in local and state taxes, and what you think you will pay at some point a decade or two into the future. Remember, these are projections. No need to harness yourself to data. Think American:

Do you believe your property’s value will increase over the next 20 years? Expect to make some big purchases during the next couple decades? Do you believe your personal income will rise between now and 2030? How about that small business you’ve just started? Expecting it to grow and pay more in corporate income taxes over the coming quarter century?

Great! Your tax increments project to be positive!

Just don’t go looking to the state for any handouts. Only certain people can leverage their tax increment projections for personal gain. TIF funds are only available to developers whose projects exceed $10-25 million.

In a reversal of the notorious private sector practice of red-lining, TIF subsidies are geographically tied to specific, mostly urban, areas. If your business plans fall outside of designated TIF zones, it does not matter how much money you plan to invest. You cannot apply. (A variety of amendments to the law have diluted this requirement, including a 2011 law expanding TIF’s to military bases and university office parks like Cold Stream Campus, operated by that billion-dollar non-profit land corporation, the University of Kentucky.

In a neoliberal world of public-private partnerships, TIF is new age IMBYism at its finest: a trickle-down governmental green-lining whose most direct effect is to bolster the bottom-lines of the already-wealthy. It’s a fuck tomorrow’s wee Peters to overpay today’s fat Pauls kind of strategy.

Today’s fat Pauls benefit in two chief ways. Long-term, TIFs enhance profits at the margins, which is how most private businesses achieve success. TIFs do this by creating separate tax districts within the city that redirects up to 80% of the fiefdom’s increased property, income, and sales taxes. In other less greedy times, we might  expect this tax growth to flow back into general funds, be deliberated upon by wise and judicious leaders, and then disbursed for city-wide needs. In the era of TIF, however, this tax growth is “captured” and handed back to our fat Paul’s. For most TIFs, this margin-enhancer will occur over a period of 20-30 years.

expect this tax growth to flow back into general funds, be deliberated upon by wise and judicious leaders, and then disbursed for city-wide needs. In the era of TIF, however, this tax growth is “captured” and handed back to our fat Paul’s. For most TIFs, this margin-enhancer will occur over a period of 20-30 years.

TIFs also serve our portly Paul’s short-term needs. Developers may finance the source project with some of their own money, but most TIF-related projects rely upon a mix of borrowed money and public tax commitments to secure investors and placate bond-rating agencies. The short-term leverage provided by TIF serves to legitimize bad projects by inflating the scope, size, and cost of them.

Consider CentrePointe. In the case of what is officially “the Phoenix Park/Courthouse TIF,” the developers initially asked for $112 million in future tax-increments for a variety of nearby improvements. In theory, these represented pressing public infrastructure needs: a tunnel across Limestone to link the proposed CentrePointe high rise development with Phoenix Park, a pedway across Upper Street to the Financial Center garage, a 331-space parking garage beneath Phoenix Park, a renovated courthouse, and an enclosed Farmer’s Market location.

A mere seven months later, September 2009, the list of publicly funded improvements did not change—but the TIF costs had dropped to $70 million. The project was so leveraged that a fluctuation in the project’s borrowing costs had created a $42 million drop in TIF commitments.

By 2013, the list of Phoenix Park/Courthouse TIF projects has been trimmed significantly. No more Farmer’s Market.  Put a hold on the courthouse renovations. Forget the pedway and tunnel. From the original list of public projects, just a private underground parking garage remains—and most of this garage will exclusively service CentrePointe tenants. Whatever tax growth the Courthouse/Phoenix Park TIF promises to bring the city, most of it seems destined to pay off an upscale, out-of-market underground parking garage to which the public will have little access.

Put a hold on the courthouse renovations. Forget the pedway and tunnel. From the original list of public projects, just a private underground parking garage remains—and most of this garage will exclusively service CentrePointe tenants. Whatever tax growth the Courthouse/Phoenix Park TIF promises to bring the city, most of it seems destined to pay off an upscale, out-of-market underground parking garage to which the public will have little access.

Kentucky TIF

While the Distillery District and Phoenix Park were Lexington’s first tax-increment zones, TIF hit the commonwealth two years earlier when state leaders went looking for creative ways to greenline the construction of downtown Louisville’s YUM! Center, home of the Louisville Cardinals.

Louisville, whose revitalized urban experience has recently purchased it the accolades of a variety of travel and food publications, was the earliest and most active user of Commonwealth TIF funds. Of the nine TIF projects approved prior to 2009 by Kentucky’s Cabinet for Economic Development, seven listed a Louisville location.

Though some Louisville TIF projects ultimately went inactive, the $2.7 billion dollar total projected cost for the nine urban projects was underwritten by $1.5 billion in pledged future state and local tax increments. On a per acre basis, the 4,938.3 acres covered under KEFDA’s Lousville TIF districts had redevelopment cost projections that averaged $546,746.85 per acre, of which the state projected to rebate $303,748.24 in taxes.

Since the Phoenix Park and Distillery District TIF districts, KEFDA has approved more Lexington TIF projects. Downtown, there is the $500,000 TIF commitment for the boutique art museum hotel 21C, which sits across Main Street from the CentrePointe (Phoenix Park) TIF.

Other projects are forthcoming.

Between the Distillery District and Phoenix Park TIF districts sits the Rupp Arena Opportunity Zone, which has been test-marketing plans for $300 million and up in publicly funded construction costs.

Between the Distillery District and Phoenix Park TIF districts sits the Rupp Arena Opportunity Zone, which has been test-marketing plans for $300 million and up in publicly funded construction costs.

The city has been shopping around developers for the land surrounding the downtown transit station; its most recent suitor previously filed for and then withdrew a TIF application to help fund an unrealized movie theatre project along Angliana Avenue.

In the East End, a TIF of nearly $17 million has been granted to ProgressLex board member Phil Houlobouk, a real estate developer when not championing progressive causes, and conservative former Vice-Mayor Mike Scanlon, also a real estate developer when not impersonating Rush Limbaugh. Amazingly, the two developers have been granted tax breaks despite having no specific development plan in mind.

On the West End, former Democrat state Senator Ben Chandler and his development consortium have been green-lighted locally for another couple million in future tax commitments for Thistle Station, a sixteen story, $34 million apartment complex whose investors seriously believe that community college students are a good bet to purchase or rent one of their projected upscale apartments.

Walking the TIF Commons

In Lexington, a river runs through most of these TIF districts. Or, a submerged creek does.

The proposed Town Branch Commons, the 2.2 mile urban linear park that promises to overtake Rupp as the Mayor’s #1 civic project, will symbolically follow the city’s submerged Town Branch Creek from its (symbolic) headwaters at Third Street’s Isaac Murphy Memorial Park to its emergence at Rupp Arena. (Symbolic is an important aesthetic for the project—the creek will mostly remain submerged under two centuries of train and auto transport infrastructure.)

Whatever its public benefits—and we’ve heard everything from safely providing passage for poor black residents from the East End to their low-pay jobs at 21C, to tourism enhancement—it is best to understand the Commons as a river bed that channels our current billion dollar flood of leveraged public-private urban investment. When completed, it will touch most of the city’s Tax Increment Finance zones.

At the Commons’ symbolic headwaters, the Connect portion of the Scape Town Branch design abuts the East End TIF zone.

The Carve portion runs past a LexTran station that has been publicly bandied about for redevelopment.

Downstream, Clean drains the Phoenix Park TIF and looks admiringly across Main Street at the modern, artsy 21C TIF zone.

After emerging at a manufactured waterfall, Scape’s Reveal portion will rush past the the Rupp Arena Arts and ReDevelopment District and its projected $300 million upgrades. This Rupp District money may or may not include another proposed TIF for redeveloping the High Street parking lot that sits across from it.

Downstream from the Scape “Commons,” the creek bends into the Distillery District TIF and begins its several-mile above-ground meander away from town and into heavily subsidized horse country.

As with all manufactured river beds, the Commons will not come cheap. Though cost estimates have yet to be released, the 2.2 miles of these Commons will most certainly require an additional tens of millions of dollars in federal grants, state incentives, regional bonding capacity, stormwater funds, and other local outlays—public money that will mainly improve the land values and business evaluations of our already-subsidized fat Pauls.

As with all manufactured river beds, the Commons will not come cheap. Though cost estimates have yet to be released, the 2.2 miles of these Commons will most certainly require an additional tens of millions of dollars in federal grants, state incentives, regional bonding capacity, stormwater funds, and other local outlays—public money that will mainly improve the land values and business evaluations of our already-subsidized fat Pauls.

And as with other important infrastructure components, you will not own these Commons. The city seems intent on separating the Town Branch linear park from the rest of our park system. As a separate entity, the Commons will receive a separate (much larger) funding stream than the amenity-starved public parks you visit every day.

And so, too, will oversight of these Commons be taken from us. As a non-park entity, the land will be governed by a separate, quasi-private, oversight board—one that, sure as the Spring floods, you can bet will be packed with empty suits intent upon, above all else, keeping their private urban interests afloat.

Part 4, “Reveal/September 28, 2011,” will be forthcoming. Essay has been revised from print version. You can view original article in June 2013 issue.

Leave a Reply