When Totality hit, I headed for Paint Lick. Lexington lay at around 90% Totality, maybe 70 miles from the Full Monty. This was close enough to cancel school, throttle work, and otherwise put off organized activity across the length and breadth of the region.

Me? I was less interested in Totality per se than in the roughly 4 hour crack of time that Lexington’s Totality- adjacent situation had afforded me. I worked until 1:00 and then loaded my Old Town Discovery 119 and assorted gear into the bed of the tacoma and struck out for the territory.

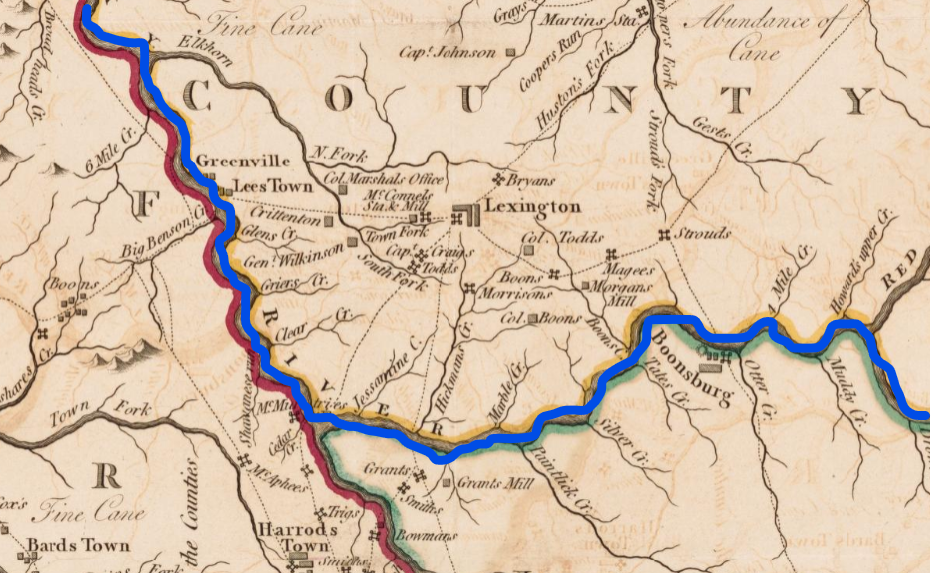

Surrounding Lexington, over 15 significant creeks feed into a semi-circular southern detour of the Kentucky River as the mainstream leaves its Appalachian mountain headwaters and cuts fitfully across the Bluegrass before resuming its ancestral northwest course to the Ohio River, somewhere beyond Frankfort.

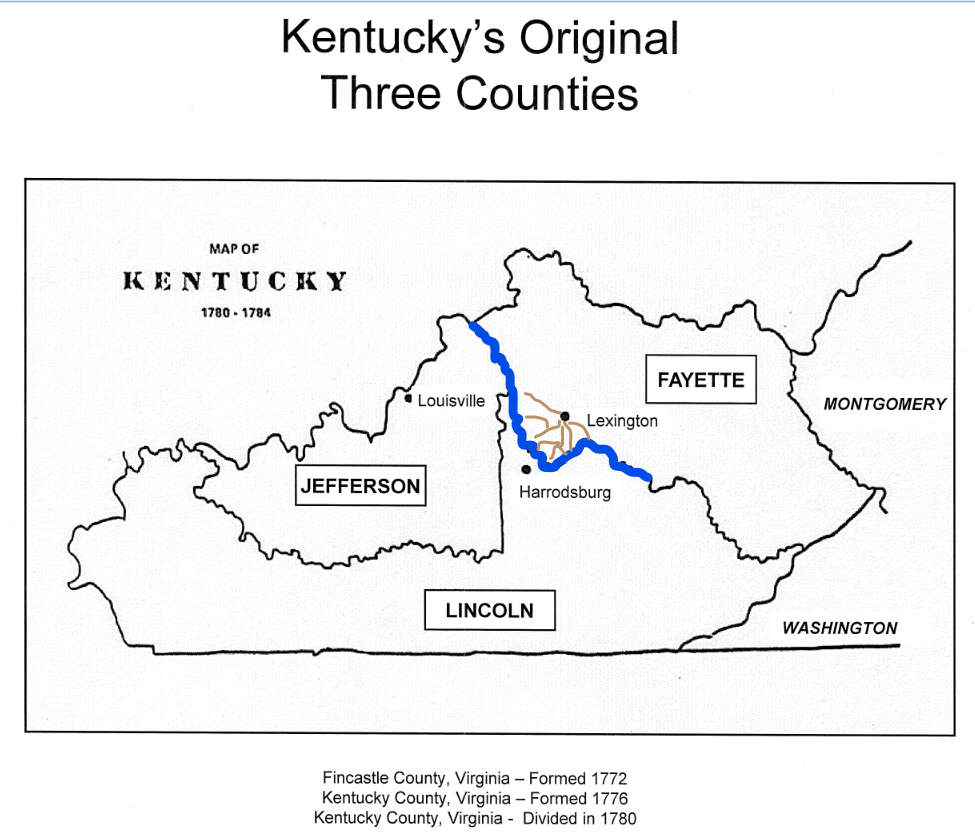

In the days before the development of the railroad, Lexington’s position as the peninsular epicenter of this southern detour was vital to its growth. Like a pre-industrial free way, the river moved goods and people into and out of the region. Its steep banks and often palisaded walls set the political borders for the Commonwealth’s original three counties.

To the east, Lexington ports like the one at Clay’s Ferry down the Richmond Pike took first-dibs on the cargo (coal, timber, iron, friends, family members) floated out of eastern Kentucky. For native Bluegrass farmers, meanwhile, the Kentucky’s great southern bend granted miles of river access upon which to ship agricultural and other products to larger commercial markets in Louisville, New Orleans, and beyond.

The days of Lexington prosperity so tightly bound to the Kentucky River drainage system have, for the moment, receded. But for the modern day paddler, Lexington’s founding situation grants us intimate access to an immense wealth of floating options.

So many float options that we Lexington paddlers can customize and optimize.

For the eclipse, I wanted a minimal drive, no shuttle, few or no people, quick paddle—and above all, to be comfortably and quietly up to my calves in some creek for the entire hour or so of Totality.

Paint Lick fit the bill in a way that Dix (too much paddle), Boone (too crowded), Elkhorn (shuttle) and other spots could not. I left home at 1:30, placed my Chaco’d feet in creek-water before the Darkening, stayed in well past the Lightening, and was back home by 6:00 to prep dinner with Peach Melba.

In the Bluegrass, where the horse dominates, we are generally pushed to equate our world class scenery with the rolling hills landscape of the thoroughbred farm. Exploration of this authentic upland scenery is mainly done by taking a country drive on a city pike, and then speed-peeping left and right at a series of privately manored fields dotted with horses. I’ve done this. Often. And it is beautiful. But also thoroughly managed and generally off-limits to me beyond my far-away gaze.

Creeks like Paint Lick and other water bodies provide the intrepid paddler with unique access to what High Bridge native Wes Houp has called the unlikely wilderness of your home place. These places are not so much untouched by humans, as areas where a present human management has receded.

I find myself drawn to water because it is unruly. It moves. It erodes. It transubstantiates. I can both get in it and pass my way upon it.

Bluegrass water cuts. Look around, and you’ll see the incisions etched willy-nilly into our porous limestone and asphalt beds, documents of deeds done long ago, reminders of what is to come.

These cuts are what make us. The landscape and nearly all of human history here are defined by them. What they brought. What they took. What they attracted. What they kept. What they didn’t.

Within these incised meanders, some of our most unruly wildness thrives still.

Part 2: Paint Lick put-in to grounding zone 1

Part 3: Downstream riffles

Leave a Reply