“In the early years of the Great Depression,” James Duane Bolin writes in Bossism and Reform in a Southern City, “the administration in Lexington was slow to grasp the problems that the city faced.”

For decades preceding 1929, Lexington had operated through small-government and low taxes, an organization of civic power that protected the wealth of the landed gentry and at the same time enabled an anti-black lawlessness (“home rule”). During these times, Bolin argues, the city’s sick, hungry, unemployed and otherwise poor residents existed off the paternal largesse of specific church flocks, a handful of local charity organizations, and Lexington political bosses like Billy Klair, the Democrat fixer who used to deliver Turkeys to the poor on Thanksgiving and Hams on Christmas.

Owing to this small-government mindset, Bolin continues, “the administration in Lexington was slow to grasp the problems that the city faced.” As a Lexington socialist active in that era’s Kentucky Worker’s Alliance commented about the inadequate response, Lexington’s political class “didn’t think it was a permanent thing….The immensity of the problem hadn’t been grappled with.”

Grapple or not, it soon became clear that the city’s traditional reliance upon bossism, private wealth and religious charity was entirely unsuited to the large-scale problems then facing it. By 1931, two years after the Stock Market crash, Bolin notes that our local government had managed a measly $162 donation to fund a single soup kitchen, a callous graciousness that was matched by the city’s Chamber of Commerce.

Lexington’s other elaborate plan to aid its struggling citizens also proved not up to the task. In the same year they were scrounging together $162 from the city budget to staff a soup kitchen, city officials asked local business owners to clip out work-availabe pledges that were published in the daily papers, to fill out these pledges, and to send them to a bureau at City Hall, where the pledged jobs would be matched to unemployed Lexingtonians (presumably the white ones, at least). “The almost total inadequacy of the plan,” Bolin writes,” was made clear when employment was found for only one carpenter, one practical nurse, one plumber, and ‘one man for yard work’ in a typical day of the bureau’s work.”

Ultimately, it would take another four Depression years, 1935, before the federal (non home-rule) New Deal would provide the programs and the funds to help relieve Lexington poverty.

I thought of this local history last month when I read about the city’s present anemic response to a predicted upcoming wave of Fayette County evictions: roughly $1 million in released Federal CARES money that will mostly go to Covid19RentalHelp, a consortium of 15 different local agencies with whom the city has existing public-private partnerships. (A second $1 million will be disbursed at some future date; the city also hopes to get access to a part of a state-wide $15 million rental assistance fund.)

Two $1 million installments and a small hand at the $15 million state-wide trough may appear to some an admirable civic attempt to help local renters who are backlogged on their rent from six months of a Covid shutdown and the erratic Covid slowdown that has followed.

But, really, the city’s present attempt at providing for its down and out citizens is soup-kitchen paltry on several fronts.

Small and short term solutions

To begin, just listen to our Chief Financial Officer, Sally Hamilton: “We expect they will go through this money in two weeks,” she told Council two weeks ago about the first $1 million installment delivered to Covid19RentalHelp.

A roughly month-long city solution not paltry enough to sway you? Consider our neighbor to the West, the one you’re always trying to one-up in one way or another: Louisville, the Cardinal City, no friend of the poor and marginalized, nevertheless set aside $21.2 million for rental assistance. Louisville, of course, is magnitudes larger than Lexington, but ask yourself: is it ten times larger? Are its leaders that much more magnanimous?

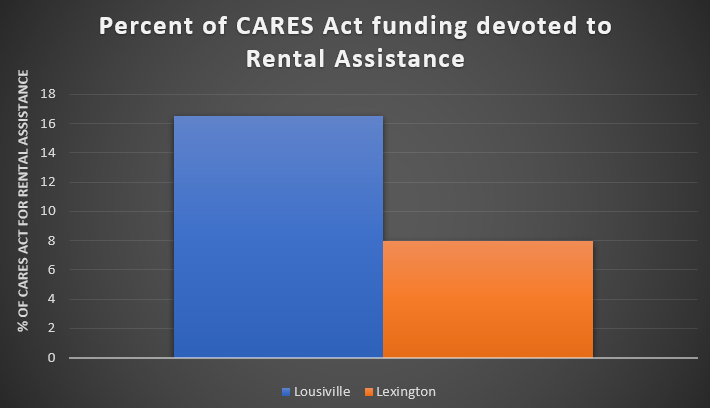

Like Lexington, Louisville received its rental assistance funds from the federal government, namely the CARES act. A comparison of the two competing cities demonstrates another way Lexington’s rental assistance funding is bush-league paltry: in its allocation of these federal dollars.

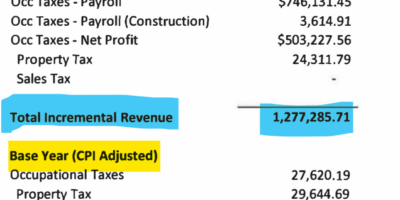

Louisville received $133 million in CARES act funding through a separate program for cities of 500,000 residents or more, a number that is roughly five times more than the $25 million Lexington ended up receiving. Though the absolute funding amounts differ significantly, one may still compare ratios. Louisville’s $22 million directed toward rental assistance represents one-sixth of its entire CARES allotment.

Lexington leaders, meanwhile, in choosing to devote $2 million toward rental assistance, were allocating a comparatively paltry one-twelfth of our $25 million CARES allotment to helping renters.

Poor resource management

In his writing on Lexington during the 1930s Great Depression, Bolin often references how the choices made by city leaders to keep taxes low produced a miniscule city budget that was unable to shift its meager resources (even if it wanted to) to address the great scale of the Depression. Because the city was so under-prepared and under-resourced, Bolin was claiming, the city was easy to overwhelm.

The Lexington of today, of course, is not a city completely averse to taxes, nor is it one bereft of resources. Yet, as in 1931, our city leaders seem ill prepared to deal with this new depression because they are either unwilling or unable to marshal the necessary sources. Even more to the point, today’s leaders seem to be pushing the same sort of paternal trickle-down solutions employed by our leaders of yore.

If our leadership in this present age seem in danger of being overwhelmed and made ineffectual like those Lexington governments of the early 1930s, surely future historians will ascribe our own follies to the misuse of our ample resources–to placing great amounts of capital in the service of a supremely fucked up set of civic values.

These values are laid bare in looking at how we have divided the rest of our $25 million CARES pie. In June, the city’s first act was to move $9.3 million CARES dollars, roughly 40% of the entire allotment, into two savings accounts, an Economic Contingency fund ($6.4 million) and a Budget Stabilization fund ($2.9 million). At the end of August, its second act was to allocate the $2 million to help renters.

Roughly speaking, then, city leaders have thus far deposited $5 in the bank (minus a nickel in account management fees) for every $1 they’ve actually circulated in CARES relief.

Meanwhile, the plan going forward is for the city to make another $9.3 million deposit into the two savings funds. Do a little math and you realize a whopping 75% of the city’s federal money that had been earmarked for providing Covid-related help to its citizens…will instead go into two savings funds.

Aid for our community partners

Our local leaders don’t normally state things outright, but there is a reason for the decided preference to stuff most of LFUC’s gifted federal money into savings accounts rather than to push it out into the community (which is what the New Deal ultimately did to help combat our last Depression, a global war among failing superpowers notwithstanding).

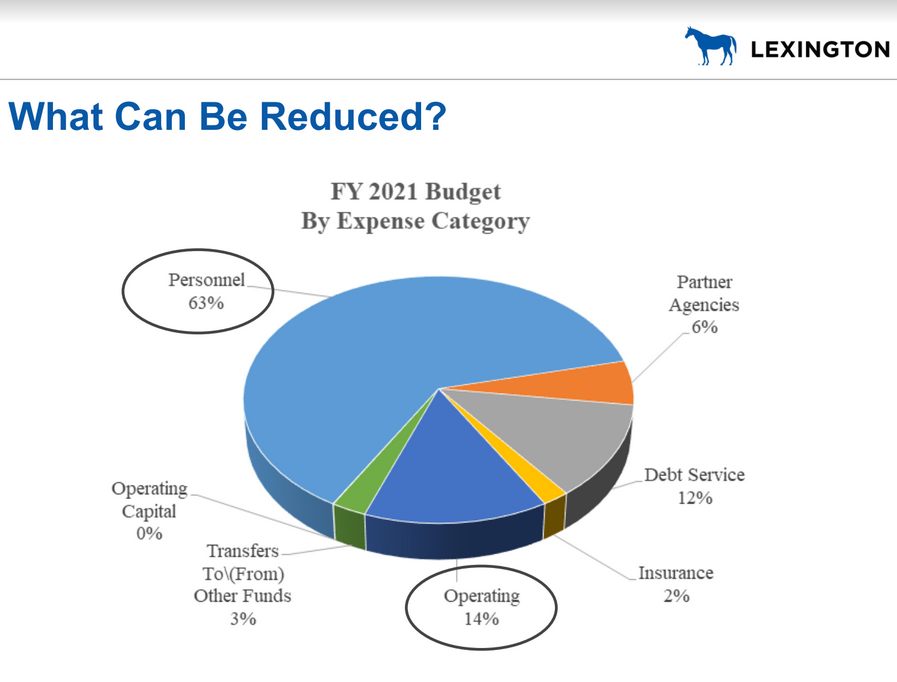

For years, Lexington has set a limit on its debt payments: it aims to keep those payments at or under 10% of the General Fund. The limit keeps our creditors happy.

But for years, bonds for city projects like the World Equestrian Games, the Rupp Arena overhaul, a refurbished Old Courthouse, road resurfacing, and new urban bike trail the Town Branch Commons have pushed the city’s annual debt payments to between 11 and 13% of its General Fund. This percentage will no doubt be challenged this coming year, as city General Fund revenues are said to have declined even as payments on the debt service remain in force.

This may not seem like much. But consider: the 2020 LFUC General Fund budget is $380 million. At 10% of our General Fund, the municipal goal of city leaders is to devote $38 million or less this year to pay off city debt and any costs associated with that debt.

Except, as it has for years, our city’s 2021 budget allocates 12% toward that debt, or $45.6 million for this upcoming year. (This $7.6 million over-budget debt payment to creditors is, yes, another way to understand the city’s $2 million allocation for rental aid as soup-kitchen paltry.)

The overwhelming transfer of COVID funds into rainy day savings accounts was mainly meant to placate credit ratings agencies like Moody’s and S&P. A downgrade in credit rating, as any credit card borrower knows, results in increased rates for borrowing and, therefore, increased debt payments. When you’re paying on a $3,000 balance, that’s one thing. But with annual $30+million payments, slight changes in borrowing rates can have large impacts.

The shifting of so much CARES money back into the city’s two Rainy Day funds was a pretty clear message to our creditors, present and future: before we will pay our citizens to stay in their homes, we will pay you for our arenas and upscale event spaces and parking garages and any other high-cost project we or our state university may conjure.

In looking at our last Great Depression, it is hard not to attribute the city’s ineffectual decisions to a paternal racism whose main goal was to protect the wealth and status of Lexington’s wealthy classes, the rest be damned.

Looking at how Lexington leaders have chosen to divvy up their federal gift of a CARES allotment, it’s hard to see how anything has changed. As we enter our new depression, these same-old, same-old priorities should give us pause.

Leave a Reply