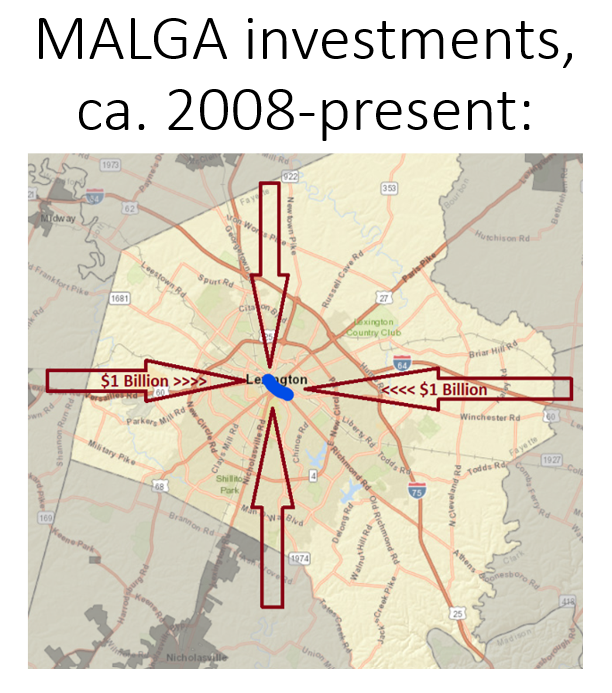

Earlier this week, I wrote a piece on what I described as MALGA urbanism. The article focused on over a decade of efforts by city leaders to implement projects whose goal was to “Make Lexington Great Again.” MALGA urbanism, I wrote, greenlighted overly large and often unnecessary upgrades to our city’s urban core and its nearby investable neighborhoods. Predictably, this design ethic has spurred run-away gentrification in the areas where it has taken hold.

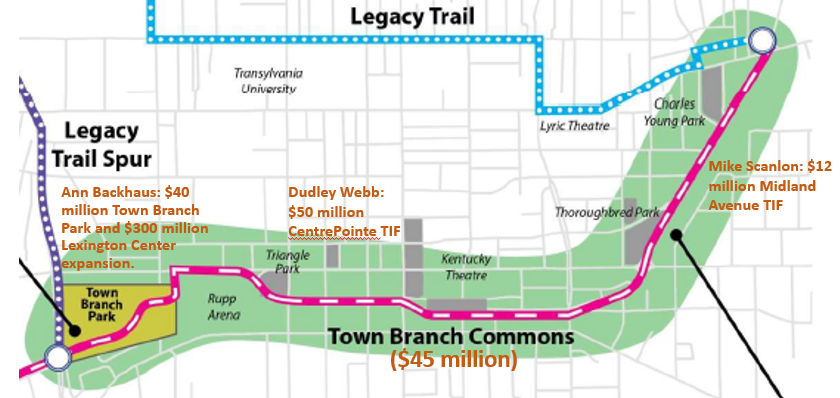

Perhaps less obvious have been the impacts upon the rest of the city. Over the past fifteen years, as MALGA leaders have devoted resources to allow an upgraded arena and a host of food halls, patissieres and craft beer establishments to prosper along a fairly small east-west belt running between the University of Kentucky and Loudon Avenue, other off-brand neighborhoods actually in need of infrastructure upgrades and other displays of community affection have been written off by MALGA leaders as unsavable suburban “deserts” (to use Town Branch Commons champion Van Meter Pettit’s formulation of his city).

A recent holiday email sent from Lexington Mayor Linda Gorton underscores this MALGA city view. Under the bold heading Fighting Food Insecurity in Lexington, the email links to a map that locates food distribution sites throughout the city, places hungry and broke residents can visit to secure free meals.

Produced by Lexington nonprofits FoodChain and GleanKY, the map represents the efforts of what Gorton describes as a broad coalition of partners, but which in reality is VisitLex, Keeneland, the Murray Family Foundation and the two nonprofits who made the food distribution map. Known collectively as Nourish Lexington, these groups have thus far raised $500,000 in funds to serve meals, with most of that money coming from a constellation of foundations whose names you often hear on NPR. As Gorton suggests in her email, it is this group that is leading the city’s response to its growing hunger problem.

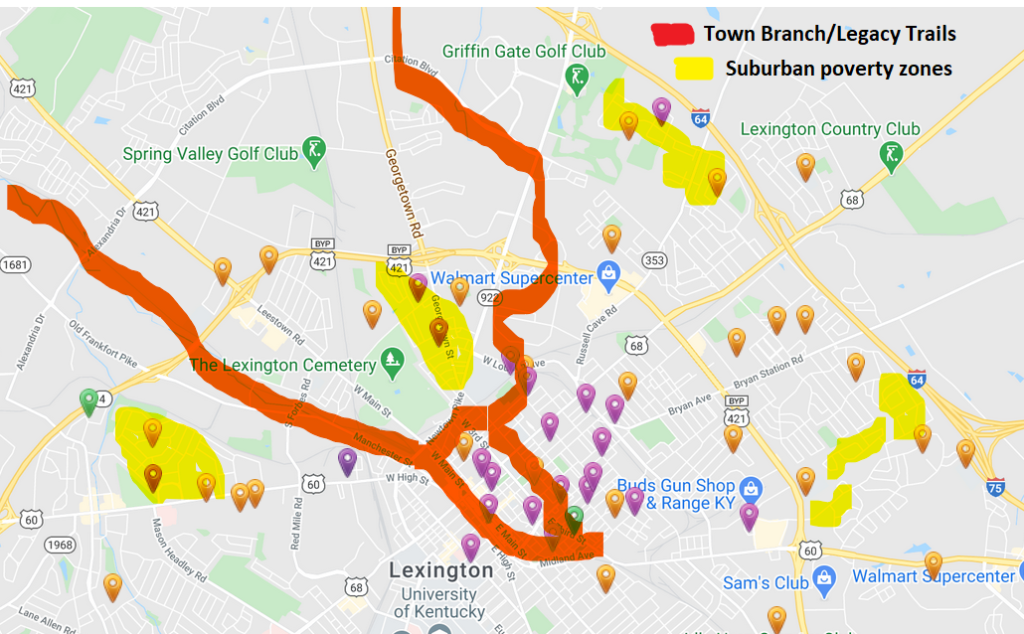

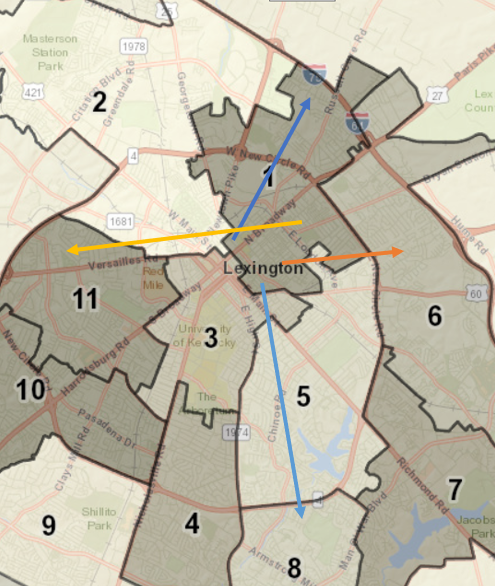

I have re-produced most of that food distribution map below. Take a moment and look at the geography of the food sites, the places where our activists at VisitLex and FoodChain and Keeneland are directing the fight against food insecurity in Lexington. Anything jump out at you?

That’s right! Fighting food insecurity skews MALGA! In fact, if you remove the orange flags, which represent Fayette County Public Schools Food Distribution sites that operate at all city schools, we can see that nearly all of our nonprofit and city and Keeneland and VisitLex efforts to fight Covid food insecurity have been fought…in MALGA-land!

Why is that?

I can imagine somebody like FoodChain founder Becca Self offering a couple explanations for the strong correlation between, on the one hand, the highly-capitalized MALGA-zone that runs from Main Street to Loudon Avenue, and on the other, her group’s choice of food distribution sites.

The most obvious might be because that’s where hungry Lexington residents live. Historically, which is to say pre-MALGA, Lexington poverty (and therefore food insecurity) has been centered across Lexington’s near northside, from the lower East End nearby Midland Ave to the upper West side beyond Douglas Park. This legacy has created an infrastructure of churches, homeless centers, food pantries and other non-profits that have a capacity to provide food and an interest in doing so. Added to this, Self might also note that funds to fight hunger are severely limited, and a strapped budget puts limits on both the location and duration of service. We can’t fix everything, after all.

But these reasons seem insufficient. Out of touch, even.

For one, over the past 20 years Lexington poverty has been moving to the suburbs, and this has occurred as large chunks of the northside have been getting significantly richer. This is not to suggest that the northside, where nearly all Nourish Lexington’s free food stations are located, is not in need of hunger relief. It is that, (1) as with most MALGA initiatives over the past decade, the Nourish Lexington partnership misses great swaths of Lexington, and (2) the clustered area where Nourish Lexington has chosen to combat hunger nearly entirely overlaps with those near-Main Street blocks that represent some of Lexington’s greatest real estate upside. Is this charity as social justice, merely a way to keep the hungry natives at bay until they are replaced, or just class-blind MALGA ignorance?

I don’t claim to know the location of all of the city’s high-poverty areas, but let’s take a look at the part of Nourish Lexington’s map that focuses on north Lexington. On it, I have highlighted in yellow a few suburban poverty areas and outlined in red the contours of our two bike trails, which were constructed over the past decade (MALGA urbanism’s gift to the people) and also, nach!, connect much of the gentrified northside.

You’ll notice two distinct patterns: First, gentrifying northside neighborhoods get saturated with 15 hot meal distributions sites (signified by the purple pin); second, off-brand and non-gentrified suburban neighborhoods have access to a paltry 4 hot meal distribution sites. Some struggling neighborhoods, it seems, are more valuable than others.

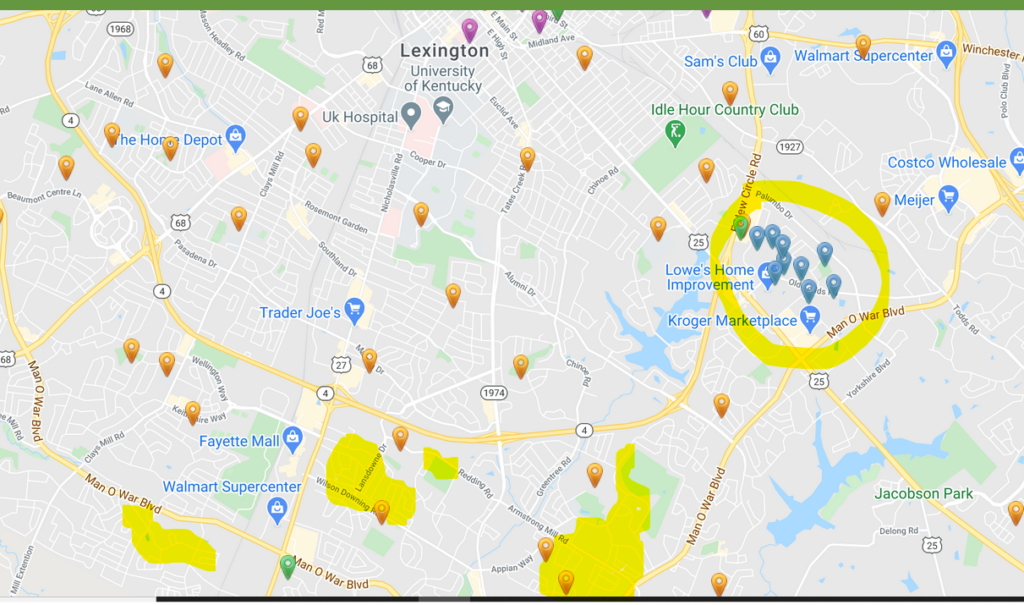

This pattern holds for south Lexington, too. While it’s not a surprise that the wealthy southside neighborhoods adjacent to the University of Kentucky have little need or desire for hot meal distribution, only 1 of the 4 more distant low-income southside neighborhoods I’ve marked receive any hot food distribution. And the one neighborhood receiving food aid, the Woodhill neighborhood off Richmond Road, gets a single Friday trip by a “Mobile Snacks” foodtruck that only children can use. It’s a 9-stop route that allows a mere 10 minutes per weekly stop. Sure hope the hungry kids of Woodhill are punctual!

If this seems like more than just an ignorant misallocation of scarce resources on the part of our nonprofit and city leaders “fighting hunger,” it’s because it probably is. MALGA ideology uses race, social justice, economic development, art, poverty–even hunger—in ways that allow moneyed interests to access and assume control over the territories they desire.

Self’s non-profit, FoodChain, sits at the northwest edge of Lexington’s gentrification zone, in a factory her husband Ben Self purchased in 2010 and transformed into the city’s first brewpub, West Sixth Brewery. That brewery, along with FoodChain, was one of the main promoters of northside entrepreneurs’ ‘capitalism for community good’ ethos that masked the displacement of low-income northsiders until the George Floyd protests took place a decade later. In fact, until three months ago, West Sixth was home to the Plantory, a self-described hub of social justice nonprofits.

Self’s non-profit partner in this fight against hunger, the Murray Family Foundation, spent 2018 not fighting hunger in Lexington, but rather donating $1 million to help build an urban park (the “Commons,” get it?) to accompany the city’s $350 million investment in Rupp Arena–a MALGA project thoroughly endorsed by another of Self’s hunger partners, VisitLex. The Murray Family Foundation is run by Wes Murray, who in addition to starting a million dollar bourbon distillery is also a significant northside land investor. In 2018, Murray was part of a trio of landlords who pushed to evict the black-owned bookstore Wild Fig from its home in the NoLi neighborhood.

The MALGA brand wants to convince us that wealthy, mostly white organizations have done their fair share to help lift up the poor and downtrodden in the urban neighborhoods they moved into. This is the image that got Self both the $500,000 in startup money from NPR-promoting foundations, and also the Mayor’s support for leading Lexington’s hunger relief efforts.

The MALGA reality, however, is that these same individuals and organizations have ever so silently overseen the removal of thousands of poor black, brown and white northside Lexington residents to suburban neighborhoods in Cardinal Valley, Eastland, Centre Parkway, Winburn, and the like.

And now they are directing their hunger relief. We should call it what it is: colonial charity.

And inconveniently for our neighbors relocating by the busload to Lexington’s new suburban deserts, these new places all exist off the MALGA map. Out of site, out of mind. Hunger be damned.

Leave a Reply