CVS, ProgressLex and building a dignified city center

By Andrew Battista

“Progress” has always been a slippery concept. It’s difficult to critique an organization that collectively pursues “progress,” just like it’s unpopular to poke holes in a community that wants to valorize its own creativity as a linchpin of social improvement. It’s harder still to define what counts as progressive, especially when what’s at stake with the progress debate is actually the ability of the community in question to enjoy the amenities that most people in Lexington would deem essential.

Recently, a group of well-intentioned public activists have formed ProgressLex, a nonprofit dedicated to social justice and “smart and sustainable economic development” in downtown Lexington. Thus far, ProgressLex has mastered several bailiwicks: the architectural aesthetics of certain downtown buildings, the traffic flow of Lexington’s downtown thoroughfares, and the brand development of Lexington as an epicenter of brainpower and social industry.

If anything, ProgressLex is a testament to the fact that if you rally enough well-connected people who are proficient with Web 2.0 media, you can elevate any personal pet-peeve to the level of community crisis. During the last week, ProgressLex has demanded that the chain drug retailer CVS, which is currently building a unit at the nexus of Main Street and Vine Street, reconsider its decision to construct a suburban-appearing unit that it claims would “be a blight” on Lexington’s downtown. ProgressLex has managed to cause a significant stir. Over 1000 people thus far have signed an online petition called “Lexington Deserves Better.” Thanks to ProgressLex, WKYT has covered the design controversy on its evening news programming, and the Lexington Herald-Leader has treated the issue with front page space and editorial commentary.

My main point of contention with ProgressLex is not its decision to question CVS’s design model, but of its method and prioritization. There are much bigger fish to fry in Lexington. In particular, we currently don’t have a downtown drug store that can serve the people who live here. The subsequent Herald-Leader editorial likened Lexington to a dysfunctional family with a “chronic inability to marshal the discipline to sustain real improvement.” ProgressLex should re-imagine its potential to act in ways that make people’s lives better and not limit themselves to a program that strives for a town that looks nicer. How our downtown should look has taken precedence over discussions of what many people who live in proximity to downtown actually need.

The appearance of mom and pop stores

According to ProgressLex Chair Danial Rowland, the proposed CVS store does not make an effort to fit in with Lexington’s downtown aesthetic.

“In fact, the design reflects a far greater effort to stamp the building with the CVS brand than to respect and respond to the downtown context,” Rowland wrote on the ProgressLex blog. “The synthetic stucco arches, for example, have no architectural integrity, make no reference to any architectural idea or form, yet they are dominant elements. Simply put, the arches are CVS signage, without the letters. This may be acceptable in the more vulgar environment of a strip mall, but not in a downtown environment where a higher degree of dignity is expected.”

Since when has suburbia been coded as “vulgar” while downtown maintains a “higher degree of dignity?” I guess this distinction depends on which part of downtown one is talking about. The complaint seems to be that CVS, which will pour lots of its own money into this project, wants its building to reflect a singular experience that their customers have come to expect. In other words, ProgressLex wants to establish a protocol where Lexington’s downtown architectural cognoscenti, not the private corporations that do business downtown, are allowed to fashion and develop a singular brand image. And that image must conjure an aura of Southern gentility, equine idolatry, and quaint hospitality, not drab suburban predictability.

ProgressLex seems to think that no private interest should impinge upon an as-of-yet unarticulated urban dreamscape without first aligning its business model or design plans with the aesthetic sensibilities of a select few citizens. Indeed, CVS developer Gary Joy told Herald-Leader reporters, it’s hard to understand what “urban design” means exactly. From what I can tell from reading the Lexington Zoning Ordinance, CVS hasn’t violated any design codes in its proposed building. Joy has even made some changes in response to complaints from parties like ProgressLex, but these changes aren’t good enough.

I suspect that when ProgressLex objects to CVS’s branding, they actually object to CVS itself. Herein lies the problem with branding: it’s the modus operandi of a corporate culture whose profit motive is usually antithetical to the values of a community. Corporate culture has so radically transformed the landscape of the United States that we can no longer imagine a retail economy that isn’t dominated by multi-national machines.

When ProgressLex yearns for a consistent urban design standard that adheres to the historical texture of surrounding neighborhoods, it wistfully wants to recall a kinder, gentler era. The decorative arches on the CVS storefront “reek of a tepid attempt to introduce quaintness,” says ProgressLex. Yet this quaint era is exactly what CVS and other suburban outfits seek to conjure through their architecture. CVS wants to evoke a nostalgic experience, shopping for medicine at the local mom-and-pop store. But Hutchinson’s Drug Store is gone, as is a pharmaceutical industry that is ethical and responsible.

Suburban architecture a la CVS is a simulacrum, a copy of a thing that never existed. It simply reproduces what we imagine it would be like to patronize an authentic establishment, and then it reproduces this experience for maximum profit. Ted’s Montana Grill looks like an old western saloon, or at least what we imagine an old western saloon might look like; the Pub near Fayette mall does for British taverns what CVS does for drugstores. It would be more accurate for ProgressLex to say that CVS is out of place not because of what its proposed store design looks like, but for what the store itself represents.

Corporate branding and downtown landscapes

ProgressLex’s argument might have more credence if Lexington had previously proven itself to be a town that refuses to let corporate interest the ways. But Lexington has always allowed the interests of a wealthy minority to dictate how its space is used.

Unfortunately, the ProgressLex architectural critique is inconsistent. We daily and freely subject ourselves to corporate advertising and branding by watching television shows, listening to radio programs (yes, even NPR), and attending (or teaching) university classes that could not take place without the revenue generated by advertising. Advertising isn’t ideal, but it’s currently the de facto system, a series of quid pro quo agreements, in which we participate every day to be informed, entertained, or invigorated. But when a company decides to build a building and advertise itself on that building, ProgressLex speaks up with pious outrage?

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not arguing that Lexington should let corporations run roughshod over its citizens. But if corporate-financed infrastructure can improve the quality and sustainability of life in our community, we might want to consider seriously the place of the buildings they produce in our eclectic, stable downtown landscape that serves many interests and increases the functionality of many peoples’ lives.

An example is the gaudy, bright red bench behind the Thomas and King downtown offices (off Short Street). The bench says “Wow,” which reflects the company promise to “wow” its customers. It looks like something you’d see at an amusement park, and it’s clear to me that the bench serves a dual purpose. It is first and foremost shameless advertising for Lexington’s most annoying restaurant company, but the bench is also intended for public beneficence; it provides people with a place to sit and enjoy downtown where no place had existed before.

A better and more obvious example is the newly-minted Fifth Third Pavilion that occupies the street adjacent to Cheapside. No structure in downtown comes close to resembling the cold, industrial steel buttresses that uphold the pavilion’s glass overhangs. I’d be curious to hear ProgressLex’s interpretation of this architectural wonder.

The Fifth Third logo that has been placed prominently at the head of the pavilion also might seem to be gratuitous advertising, but I think over time we’ll realize that this structure will make the Farmer’s Market better and allow it to last longer. The pavilion will host festivals, fairs, concerts, and other events that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible, or at least wouldn’t have been as enjoyable for everyone. And the pavilion certainly wouldn’t have been built without the $750,000 donation from Fifth Third Bank.

My point is that we need to entertain the reality that private enterprises can provide benefits and services to a community that public organizations have been unwilling or unable to accomplish. This is the neoliberal dream. At the least, I’d like to see a consistent attitude toward branding from Lexington’s creative class.

Building on history: the East corridor’s racialized landscapes

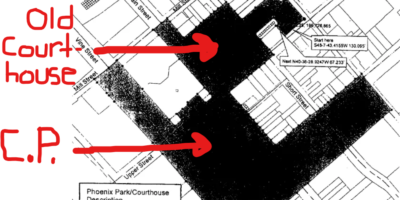

One of the reasons why ProgressLex thinks we “deserve better” than what CVS has pitched is because the nexus of Vine and Main Street has been a particularly contested space for at least 25 years in Lexington. As the aforementioned WKYT news story suggests, what gets built on this corner is important because it visually sets the tone for people as they drive into downtown Lexington. It’s a prime space to inflect Lexington’s brand and communicate our core values.

The folks at ProgressLex might already know that the space across the street has already been branded. Twenty years ago, the Triangle Foundation, a private group of wealthy philanthropists (yesterday’s rendition of ProgressLex) saw the journey into downtown via Main Street as a way to permanently associate Lexington with horse racing and the bucolic ideal of thoroughbred culture. Ignoring public sentiment or input of any kind, the Triangle Foundation designed and privately funded Thoroughbred Park, a striking paean to the equine industry and Kentucky’s rolling bluegrass hills.

Rich Schein, a Professor of Geography at the University of Kentucky, has argued that while Thoroughbred Park is a deliberate attempt to beautify Lexington, it advances a brand that depicts a highly selective picture of downtown Lexington’s past and future. The park is what he calls a racialized landscape because it promotes an idealized civic image that has been built upon Lexington’s racial inequalities. The horses and artificial bluegrass hills literally sequester the poor, historically black East End neighborhood, hiding it from view as people look out their car windows as they drive down the Main Street corridor.

What people don’t see when they drive into downtown, thanks to Thoroughbred Park, is a neighborhood that needs access to a drug store. The four or five blocks that stretch out directly behind the artificial hills comprise a community, the William Wells Brown Neighborhood Association, whose mean annual income as of the 2000 census was $14,570, or less than one-third of the mean annual income of all other areas in Fayette County (I expect that when the 2010 census data becomes available, we’ll discover that this ratio of income disparity will be roughly the same). In the East End, almost half (45 percent) of all homes are in substandard or worse condition.

Many people who live in the downtown area have no private transportation; locating medicine and getting groceries require a ride across town. As someone who lives 0.4 miles away from the new CVS, I’ll have no problem walking or biking there to pick up supplies. And I know that many other people who live near me, behind Thoroughbred Park, will also walk or bike there as well.

My charge to ProgressLex is that the group avoid succumbing to the prediction offered by the Herald-Leader editors. They are right to point out that human capital is finite: “burnout is inevitable for all but a few. Volunteers have lives to live and they wear out when they feel they are fighting the same battles over and over.” Perhaps aesthetics should take a back seat to other progressive concerns, like going after absentee and apathetic landlords, who collect rent from the East End and let houses there languish in substandard conditions. These people deserve better.

Andrew Battista blogs at http://thewellwroughturn.wordpress.com

Leave a Reply