A Colombia-Kentucky conversation

By Betsy Taylor

The global economy is devastating small-scale farming. Can small farmers create global solidarity to fight for a more level playing field? Last October, a leader of Colombian small farmers visited Lexington—catalyzing fascinating discussions that showed both the promise and the limits of such global solidarity-building.

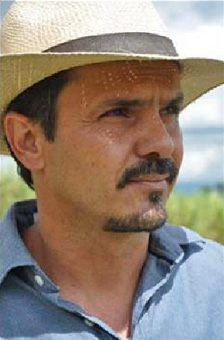

John Henry Gonzalez Duque, from Colombia and co-founder of the Small Scale Farmers Movement of Cajibio. Photo courtesy of Witness for Peace.

For three weeks in October, John Henry Gonzalez Duque toured the southeastern U.S. to communicate a grassroots, South American perspective. Gonzalez Duque is a small farmer from the southwest part of Colombia and co-founder of the Small Scale Farmers Movement of Cajibio. Gonzalez Duque’s tour of the U.S. was sponsored by Witness for Peace, a grassroots group which began in the 1980s struggle against U.S. involvement in Central American wars and now works for “peace, justice and sustainable economies in the Americas by changing U.S. policies and corporate practices which contribute to poverty and oppression in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Carlos Cruz (who works in Colombia on Witness for Peace’s international team) traveled with Gonzalez Duque and provided excellent translation.

On October 18, Professor Rebecca Glasscock organized several events at Bluegrass Community and Technical College (BCTC) for students and the general public to engage with this courageous Columbian. As I listened to these discussions, I swung between hope and despair. The hope came from the power, practicality, and eloquence of Gonzalez Duque’s moral and political vision. I felt the shock of recognition: his points echoed recent conversations with farmers at Lexington Farmers’ Markets and in Kentucky citizen groups like the Community Farm Alliance and the Sustainable Communities Network. Can widely scattered farmers’ movements be maturing into a vision for a new economy that can build common political platforms in North and South America? Can struggles against common global forces create solidarity across highly localized struggles?

But, that is where the despair comes. Gonzalez Duque arrived in Lexington on October 21, just five days after President Obama pushed Colombia-U.S. trade agreements through Congress, agreements that candidate Obama had described in 2008 as potentially complicit in the murder of labor and other activists, in the displacement and immiseration of small scale producers, in ecological devastation, and in job loss. If we listen to Gonzalez Duque’s reports from South America, we learn a lot about the structural forces that make President Obama different from candidate Obama.

Mobilizing a minga

Gonzalez Duque’s vivid photos and stories conveyed the creativity and scope of social mobilization in Colombia in recent years. The mission of his organization is “to promote a decent and dignified life for small scale farmers, with water and food security and land ownership rights.” In 2008, they joined a people’s congress of activists from across Colombia which included a public debate with Colombian president Alvaro Uribe, followed by a 400-mile march of over 50,000 people to Bogota, the country’s capital.

They call such a people’s congress, a “minga.” “Minga” is an old Quechua word meaning “collective work” and connotes autonomous self-organization. In recent Andean indigenous and peasant movements, the word has been retooled for use in contemporary struggles to refer to deliberative grassroots councils leading to visions for action. (For more on this as a kind of “policy making from below,” see anthropologist Deborah Poole’s article in NACLA Report in February 2009).

These Andean movements (like the Zapatistas in Central America) are transforming pre-state, pre-hispanic organizational forms, and philosophies of democracy in order to solve twenty-first century problems. Each year, the national minga focuses on a theme such as land-territory-sovereignty, or social and community resistance. A minga brings activists together from diverse movements across Colombia, including indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities, women’s groups, trade unionists, and students. These mingas proactively and collectively envision a society and economy that will secure their rights and take care of nature. They then draft the laws they would like elected government to enact in order to manifest this vision.

In discussion, Gonzalez Duque noted similarities between mingas and the people’s assemblies springing up in the Occupy movement, Tahrir Square, and elsewhere. He eagerly visited the Occupy Lexington encampment on Main Street, and while there, recruited an individual to attend his evening talk. Gonzalez Duque was also very interested in citizen struggles in Kentucky which parallel Colombia’s, such as movements against mountaintop removal and for local food and small farmers. He was excited to learn about the writings of Kentuckian Wendell Berry and was disappointed not to be able to visit him. The evening event at BCTC included a delicious meal with local vegetables and meats contributed and cooked by the participants (many associated with Witness for Peace and other social and environmental justice organizations), which provided a lively, happy setting for sharing stories and building solidarity.

Discussion during John Henry Gonzalez Duque’s Witness for Peace tour. Photo courtesy of Carlos Alejandro.

Gonzalez Duque mixed creative, network-building hope with hard-headed analysis of macrostructural trends that threaten his moral goals. Colombia now, he said, must be understood within the last 45 years of history. He described how loans from the U.S., the World Bank, and others have been used to justify waves of neoliberal “structural adjustment policy” since the mid-1960s, including the privatization of water, education, and health services, the dismantling of protections for workers and national business, and the preferential treatment of U.S. multinational corporations and direct foreign investment.

Neoliberal effects

Columbia’s history shows the close connections between neoliberalism, militarization, and violence. Gonzalez Duque spoke about how political space for civil society shrank as terror escalated between left-wing armed insurgencies and right-wing government and paramilitary repression. The U.S. has poured money into the Colombian military (over $10 billion in the past decade according to Amnesty International), primarily through “Plan Colombia,” which was set up in 1999 to decrease narcotic traffic and counter-insurgency.

However, the effect of Plan Colombia has been to devastate small farmers and to destroy the conditions for alternative rural economic development besides coca production. Mass toxic fumigation from the air (to combat coca growing) severely damages water, fields, people’s health, and ecological mega-biodiversity. Paramilitary groups with shadowy support from official and corporate entities are key in the horrifying violence against labor and other activists. The International Trade Union Confederation estimates that over 2,800 trade union leaders have been murdered since 1986, and 51 assassinated in 2010. (However, the number could be much higher.) This military and economic violence has displaced five million people—almost ten percent of the population, more than any other country in the world.

I dread the blather of another presidential election year: highly packaged talk circling so far from actual national and world problems, or what ordinary citizens think and need. Outside of that political spotlight, seasoned and tested political and moral visions are emerging in diverse citizen movements around the world. The lively, warm, and substantive talk between North and South America that happened at BCTC on October 18 suggests how much these diverse movements might have in common, if common political platforms can be built.

But, how can we translate this citizen energy into real political action and policy change? The real change must come at the commanding heights of global trade and finance, where corporations that are larger than most nations have primary control over policy writing and first access to elected politicians whose campaigns they largely fund.

The two Obamas

In 2008, John Nichols applauded candidate Obama for opposing a NAFTA-style trade agreement between Colombia and the U.S., saying that his moral stand showed a clear understanding that America needs to fundamentally change the macrostructures of foreign trade.

But, on October 12, 2011, President Obama pushed “Free Trade” agreements with Colombia through Congress against the vehement opposition of the large majority of his party, labor unions, many mainline faith groups, and peace and justice citizens’ organizations. In 2011, Nichols excoriated President Obama for ignoring strong data suggesting the negative impacts on American workers.

However, it is as important to ask about the impact on Columbian workers and land. Obama claims that the affiliated Action Plan which describes desirable environmental and social justice standards is sufficient. Unfortunately, these standards are mere descriptive goals without enforceable mechanisms to punish human rights violations and any failures in meeting social or environmental benchmarks.

Some people act as if it is an obscure puzzle that candidate Obama (with all that intelligence and eloquence) seems so different from President Obama (so timid and small bore in policies and programs). I would argue that things look much simpler if you follow the money. Curious about how the Colombia-U.S. “free” trade treaty passed? Go to the White House website where an April 2011 announcement lists the large corporations (or their trade groups) who supported this treaty. There is not a single organization on this list that represents civil society, small farmers, faith or labor groups.

Many of the corporations which are listed by name, or represented by lobbying groups on this list, have been receiving preferential treatment from right-wing Colombian governments for years (e.g., Caterpillar, Monsanto, United Fruit, Occidental Petroleum) and many are closely linked with the Colombian military which depends on U.S. military aid (e.g., Dyncorp, Lockheed Martin, Dow Chemical). Some of the U.S. corporations have had power in Colombia for decades and, in the last 10 years, some have been sued or fined for paying paramilitary squads to kill labor activists (Coco-Cola, Drummond, Chiquita).

This corporate-driven U.S. trade policy is antithetical to the vision of democratically planned, small scale, and sustainable economy which John Henry Gonzalez Duque shared with us last October—and which found such resonance among Kentuckians working for local food systems and social justice.

Leave a Reply