On the relative cost difference between City and County cronyism

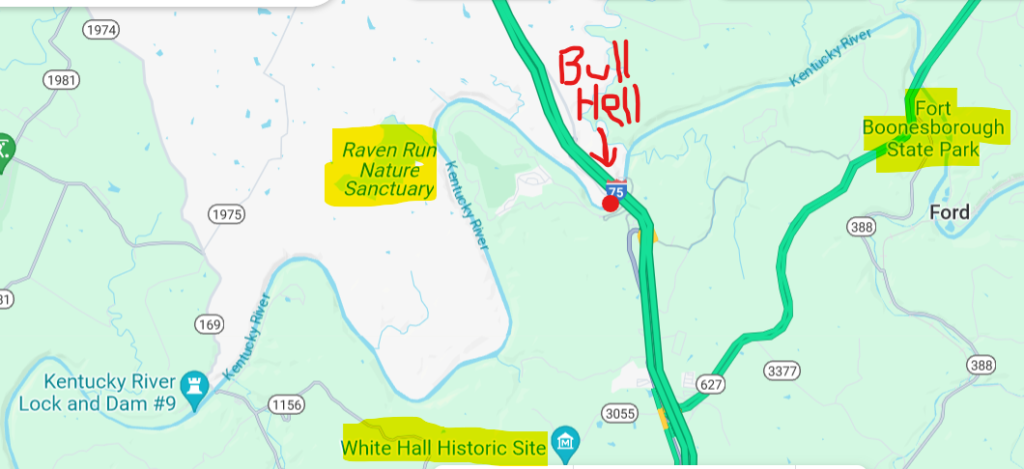

In summer 2022, the city of Lexington announced it had purchased 30 acres of Fayette County bottomland in order to establish the city’s first-ever public river access to the Kentucky River. Response to the news, including NoC’s take All Hail Bull Hell, was generally positive.

Notable, though, was a group of Lexington Herald Leader commenters who lambasted the $1.16 million that the city had paid, a price they felt was inflated. Their implication: a fat cat cronyism had led city leaders to over-enrich a private large land-owner in a way that distorted civic priorities.

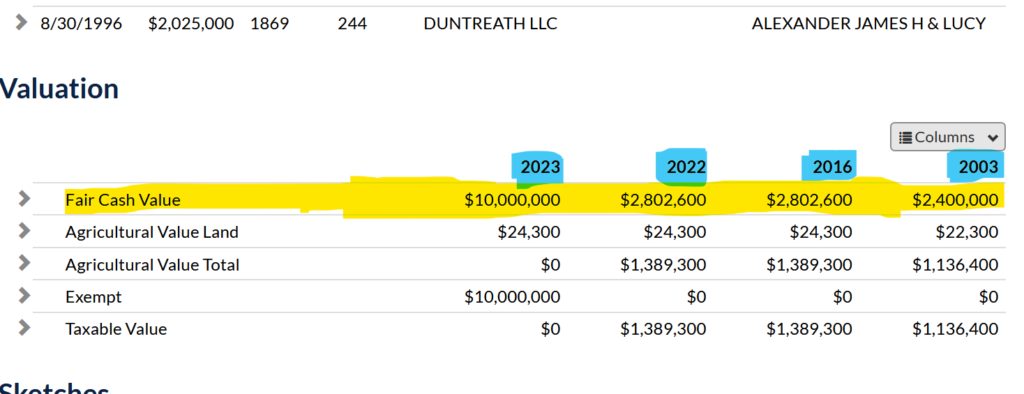

The commenters’ concern had merit. Fat cat cronyism was seemingly in the air in Lexington in July 2022. The previous April, news broke that Fayette County Public Schools (FCPS) had paid $10.1 million to the nephew of land-jobber Dudley Webb for an in-town 35-acre allotment that had long been assessed at $2.8 million.

Two years earlier, the same FCPS had purchased the abandoned Lexington Herald Leader building for $7.5 million, after it had sat on the market for over half-a-decade.

The FCPS purchase was just two years removed from a 2018 plan by Lexington Mayor Jim Gray and his City Council to buy the HL building for $151 million and then enter into a 25-year, rent-to-own public-private partnership with Lexington Center Board Chairman Craig Turner to build a new city hall at the site. This deal, the LFUCG–Craig Turner–Herald Leader deal, was so crony that the feds had to be called in, and Turner’s bag man sent to jail for bribery.

So there was ample precedent in the summer of 2022 for Herald Leader commenters to express concerns of land-jobbing civic cronyism.

At the same time, I also found these concerns somewhat wanting in the specific case of the 30 water-front acres recently named Kelley’s Landing at Bull Hell Park. To be sure, the city paid an inflated cost of $1.16 million for the land, or around $40,000 per acre.

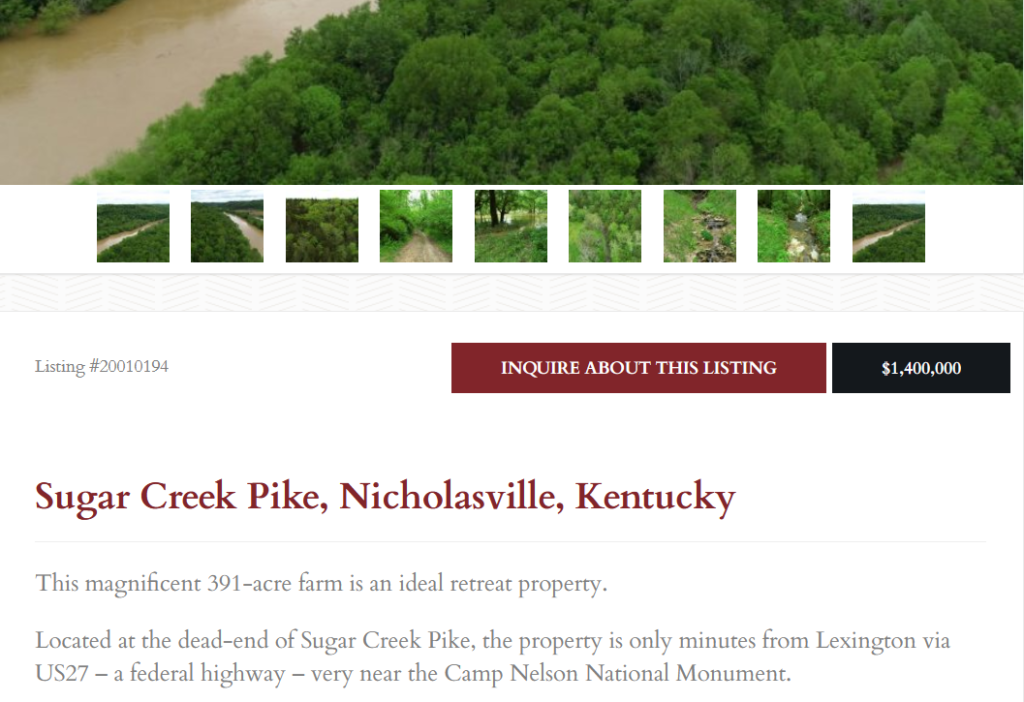

Here, for example, is a 391-acre property along a comparable stretch of Kentucky River palisades offered for $1.25 million, around $3,000/acre.

I also recall a 200-acre place for sale a few years ago that was located just upriver from Bull Hell and across from the mouth of Boone Creek. I can’t find the expired listing online, but I recall an asking price around $1.5 million. Notably, both properties sat (or are sitting) for a long time and experienced price-cuts.

River acreage can be difficult to sell because of flooding and access. I’ve personally seen much of the future acreage for Bull Hell submerged under several feet of frothy brown water. Though one may carve out a limited residential existence along the bottoms of the Kentucky River palisades, business is limited and often difficult to establish.

Consequently, river acreage along this stretch is primarily valuable as private retreat, limited cattle farm, or micro-scale land-jobbing, all of which require a limited set of niche purchasers possessing a fair amount of wealth to purchase the large acreage allotments. If offered on the public market, I’d guess that the the future Bull Hell Park could have commanded $400-700,000 dollars.

So yeah. In a niche market, the city likely over-paid the Kelley’s by something like $500,000. And let’s assume another $800,000 or more in infrastructure upgrades to ready the park for public use. This infrastructure projection is also high and comes with its own legacy overpayments that you can read us bitch about here, but when added to the purchase price, it brings total city investment to $2-2.5 million.

To me, $2.5 million is a small price for Lexington’s first-ever (!) public access to what is by far the city’s most defining waterway.

It will provide citizens direct access to a 19-mile, unobstructed, already-up-and-flowing, automobile-free blueway trail through a geologically breathtaking palisades saturated with historical resonance; and a likely accompanying 20 acre-ish basic riverside park of some fashion.

As a bonus, Bull Hell will showcase a true private-sector regional treasure of the greater Kentucky River Valley county-side, the most excellent Proud Mary’s Barbeque. And it will sit within a half-day paddle of a public-sector State Park and a wildly successful county park, along with two non-profit nature preserves.

Could the city have paid less to acquire the property and done a more efficient job of installing a put-in for boaters to access the Kentucky River–an easy and cheap task that city-leaders have yet to accomplish across two years?

You betcha. But at this point in the development of Bull Hell Park, the civic costs are relatively low, the community grift relatively small, and the upsides quite immense.

You may disagree with my accounting. At least one local blogger seems determined to rename Kelley’s Landing as “Millionaire’s Park.“

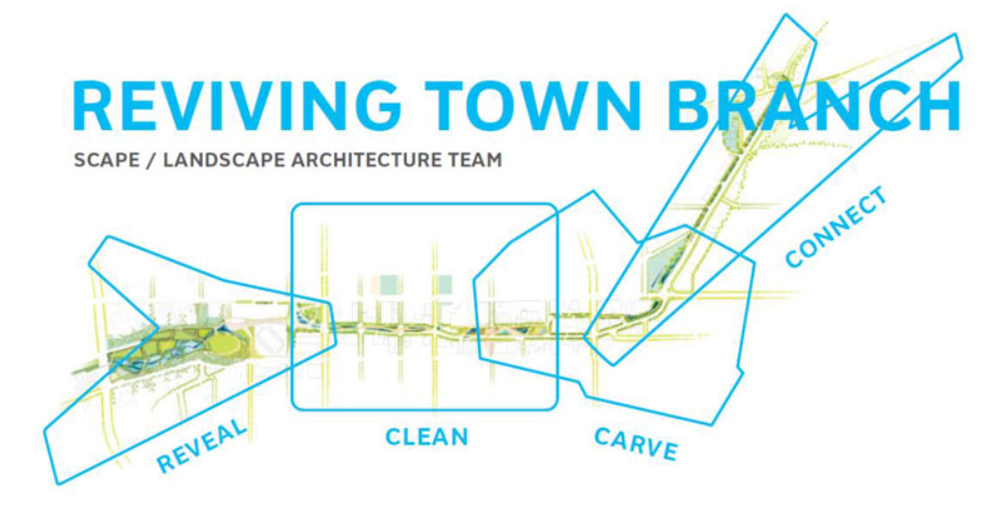

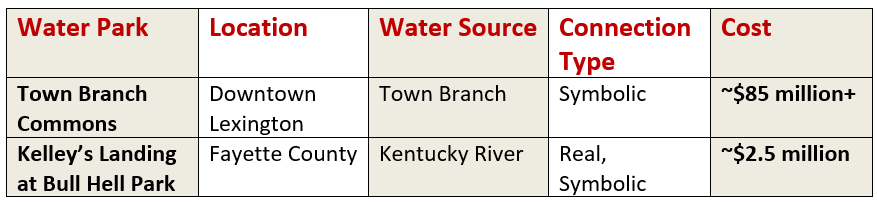

So let’s compare the fat cat cronyism of “Millionaire’s Landing” at Bull Hell to the other major water-based park developed by Lexington leaders over these past 20 years: the 2.2 mile Town Branch (TB) Commons Greenway and Park.

TB Commmons runs from Rupp Arena to the MET development at the intersection of Third Street and Midland Avenue. The price tag for this ribbon of urban Lexington greenway now exceeds $85 million.

Unlike Bull Hell, though, infrastructure for TB Commons (when completed) will not exactly connect residents to their historic downtown watershed. Lexington’s civic investment mostly just provides symbolic and ephemeral connections to TB’s namesake watersource–inspiration, if not authentic direct connection.

IRL, Lexington’s TB users must still dodge trucks and Teslas and all manner of other things at every one of its over ten traffic crossings. Here for you artsy types is a visual of this cost comparison between the city’s two water-oriented civic projects:

Why the vast difference in costs between Town Branch Commons and Bull Hell Park?

Clearly, there is a millionaire’s park in Lexington-Fayette Urban County, and it aint Bull Hell. But the question arises. Why the stark difference in costs and delivered amenities?

One reason surely arises from a difference between Lexington and Fayette Urban County cronyisms. Large and strategically placed landowners exist in both spheres, but the past decades have seen a considerable power shift into the Lexington brand.

The $85 million Town Branch Commons is infrastructure by and for members of the Make Lexington Great Again (MaLGA) coalition, a seemingly populist movement of progressive professionals taking orders from the city’s millionaire class, who claimed power during the mayoral administration of Jim Gray.

You know MaLGA investments intimately from the past 2 decades you’ve lived here: UK basketball, show horses, local heritage and craft spirits, all packed into a quaint State U city center and surrounded by a beautiful bluegrass countryside. MaLGA brand is what makes us world class, they say, and economically competitive against other fash fabulous cities on the move.

There are two problems with MaLGA brand.

First: as an item of consumption, the MaLGA brand is most accessible to the sort of globe-trotting professional class that comprise the upper crust 10% and their boot-strapping aspirational strivers. Horses, craft spirits and high-end college basketball are not cheap individual pursuits in which to participate, and they require large infusions of money to maintain.

Put differently, it costs a lot to attend a UK basketball game or Tyler Childers concert, or to spend a day at Keeneland betting on the ponies followed by a drop into downtown for some craft spirits and farm fresh food. Here is an AI-generated image from a Lexington blog that playfully spotlights the consumption side of this MaLGA brand ideal:

Second: MaLGA brand has only a limited few authentic geographic locations within the county in which to express itself. Thus, the practical owners of the Lexington brand–millionaire horse farmers, the University of Kentucky, Main Street building owners, craft spirit providers–are able to hoard access to it.

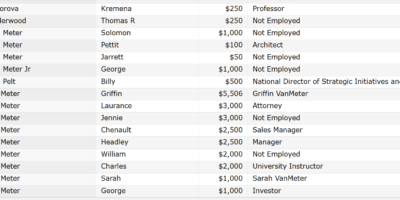

This hoarding promotes conditions for a Lexington cronyism that over-invests in certain places (theirs) while under-investing in others (yours). Here is MaLGA thought-leader Van Meter Pettit, who in some settings would not look out of place next to AI MaLGA, asserting the benefits for MaLGA value-hoarding to Lexington Herald Leader readers in 2013:

Like a well in the desert, our downtown is so small and intimate that every option for maximizing its quality and economic potential is essential to pursue.

Van Meter pettit, “Town Branch commons is path to prosperity“

Consider, MaLGA ideology in 2010 would prod the city into allocating nearly $300 million in public investment to hold an olympics of equine eventing. Or, a decade later, into legitimizing a $350 million “Gold Standard” upgrade of Rupp Arena.

These were two big ticket items to make the Lexington brand world class. Over the past decade, though, MaLGA has also delivered a slew of lesser subsidies for a modern art and other Rupp-adjacent hotels, sent saturation media coverage into distillery districts, pushed economic planning into the realm of entertainment zone curation, and normalized the dogged and doddering citywide pursuit of authentic world classism.

The $85 million, 2.2 mile TB Commons could quietly prove to be the most expensive bike lane in city history because it runs through the subsidized urban well of the MaLGA landscape.

TB is a true millionaire’s park, rebranded for the psycho-social benefit of its patrons as an all-encompassing “Commons.” Even the trail’s marginal-utility, hockey-stick shaped, 2.2 mile geomorphology manages to contort to the Lexington brand: it was intentionally fashioned to run between the city’s Legacy and Town Branch trails, both of which mainline its users into horse country.

By comparison, Bull Hell Park resides quite outside the MaLGA brand. Bull Hell is not upland horse country anchored around old gringo Lexington forts where $1.2 million doesn’t even qualify you for TIF subsidies. It is worthless flooded bottomland whose geomorphology has produced a thousands-year-old history of native crossings that continue even today.

Even the low-cost aesthetics of Bull Hell differ. The fake dribbly symbolism of the TB Commons would surely not survive the damned currents of the Kentucky River in actual flood stage. Nor can the $1 billion in new MaLGA architecture lining TB Commons (much of it like our Commons subsidized by the city and state) ever hope to measure up to the never-ending blocks of 25-story ordovician palisades that frame in Bull Hell and its entire 19-mile inner-bluegrass run of Pool 9.

All of which is to say that Bull Hell is not really Lexington at all. But it is Fayette Urban County (FUC) as all get out.

LFUCG surely paid above market rate to the John Kelley family for its 30 acres of mostly floodable bottomland. In this, the Kelleys are not much different than the Webbs or Browns or Greenbergs or Turners or handful of other landowners who have profited greatly from making equine and downtown Lexington great again.

The Kelley family ran an early version of a QuikEMart and farmed the bottoms of Bull Hell from the 1930s until it was no longer profitable to do so. Years later, as the heirs found themselves holding an abandoned though somewhat unique property that the city desired, the family extracted extra value in the deal.

This is on the order of what housing experts might counsel longtime urban residents with title to deteriorating homes to do. I’m sure the onetime windfall from the city’s $1.2 million purchase price meant a lot to the Kelleys and their heirs.

Speaking as a citizen, I’ll take this infinitely cheaper and more broadly scattered FUC cronyism over its significantly more costly and geographically focused Lexington relative. It’s about community value. And native curiosity.

For the price of 1 TB Commons, I get access to over 40 Bull Hells scattered across our Fayette Urban County community. I’ll take that sort of crony deal any day of the week over the high-cost, low-choice menu currently on offer by its MaLGA cousin.

Paul Oliva

Nice one. Yeah I agree with most, but not all of this when you put it like that.

(The ‘Millionaire’s Park’ was an attempt to reference Bluegrass Community Foundation’s misplaced priorities and the oddly named ‘Greater Lexington Fund’ … Not holding my breath that it will catch on.)

Good article!

Paul Oliva

oops meant to say “I agree with most, IF not all of this when you put it like that.”