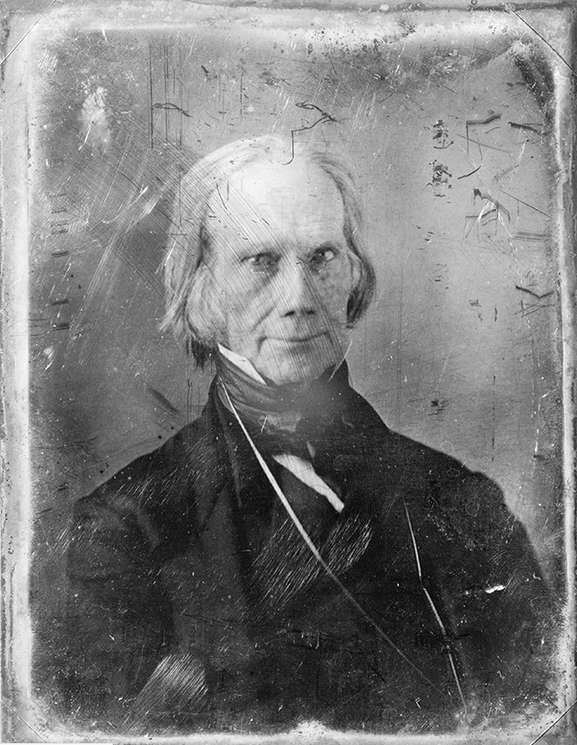

In 1777, Henry Clay was born a child of privilege, his father being a wealthy Baptist minister who found no moral, ethical, or religious problems with the institution of slavery and who personally owned some twenty human beings. Upon his father’s death, young Henry inherited two enslaved persons, thus beginning a lifetime of owning, purchasing, abusing, beating, raping, selling, profiting from, and bequeathing human beings.

At the age of 20, Henry Clay began his legal career in Lexington, at 22 he was married, and at 26 years old, he began his life as a career politico by being elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives. In 1804, construction began on the mansion at the slave labor camp that Clay named “Ashland.”

Henry Clay served in a variety of political roles — from state representative to U.S. Speaker of the House to terms in the U.S. Senate to Secretary of State. He also helped establish the American Colonization Society, which sought to emigrate previously enslaved but freed Americans to a colony in Africa.

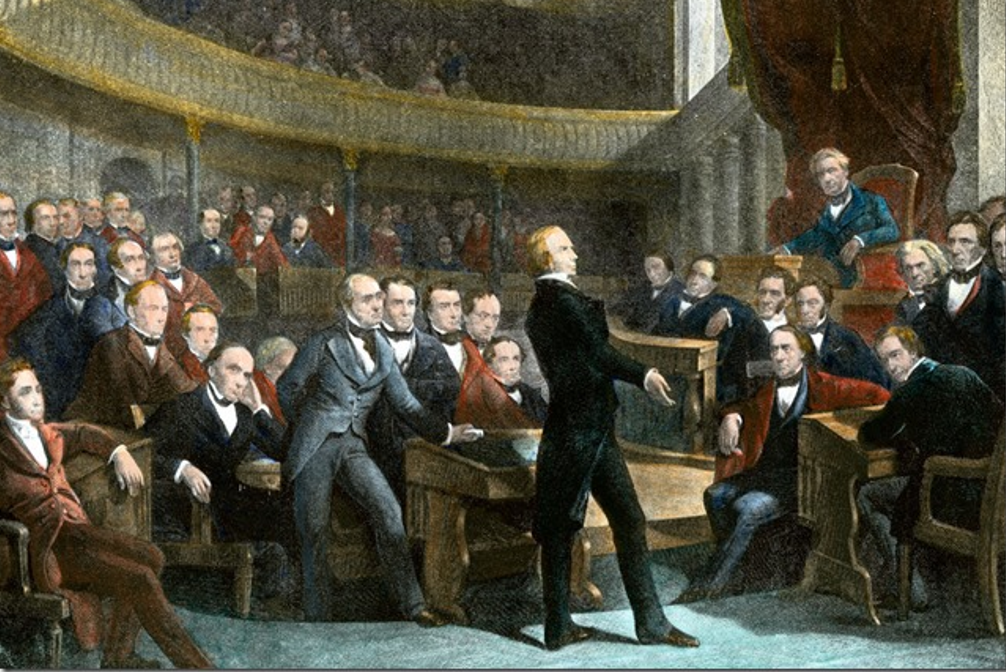

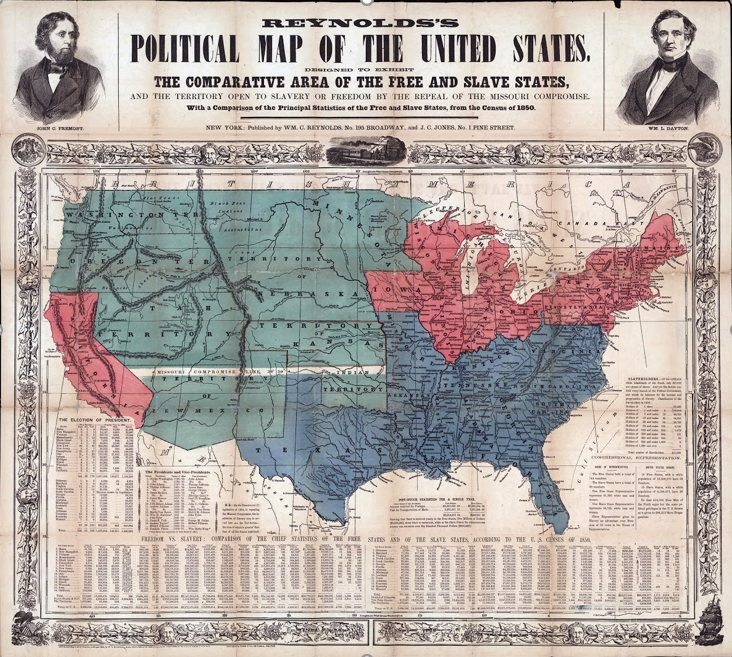

Henry Clay is perhaps best known as the politico who engineered the 1850 “Missouri Compromise.” In a nutshell, the Missouri Compromise preserved and protected the institution of slavery by admitting Missouri as a slave state, Maine as a “free state,” and a prohibition of slavery north of the 360 30′ parallel in the area obtained by the Louisiana purchase, except of course in Missouri.

This gerrymandered, jury rigged, patchwork agreement was really only a solution depending on how the problem was stated. If one was primarily concerned about preserving the institution of slavery, then it was admired and later trumpeted, even today by apologists, as somehow “saving the Union.” But if the problem was ending slavery, then the compromise was a total failure. The estimated 3,500,000 enslaved people would not have been enamored by the “solution” engineered by Henry Clay that consigned them to remain enslaved. The veneration of Clay’s compromise, even today, also sidesteps the more fundamental, existential question of whether a system founded upon lies, hypocrisy, overt racism, and the enslavement of human beings was worth saving and preserving in that form at all.

A speech given by Mr. Lewis Richardson

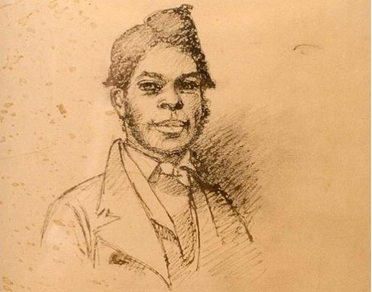

In the spirit of the holiday season, below please find a transcription of a speech given 175 years ago by Mr. Lewis Richardson in the Christmas season of December 1846 at a church in Amherstburgh, Ontario. The speech is about his life at the home of Lexington’s beloved, revered, enshrined, and most famous statesman, Henry Clay.

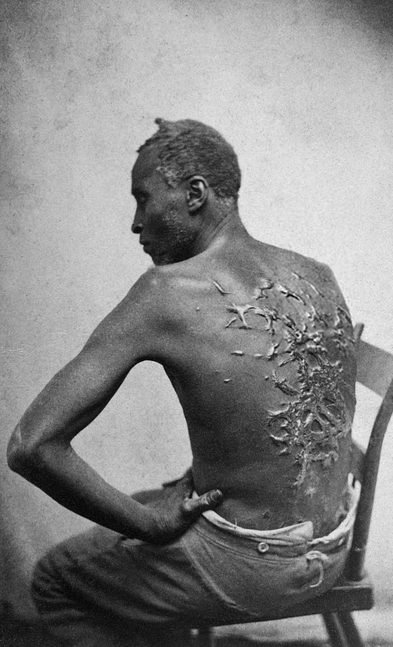

Mr. Richardson was born an enslaved person, and for the last nine years of his enslavement, he was purchased and owned by Henry Clay. In this speech, Mr. Richardson talks a bit about his life at the slave labor camp called Ashland and an incident that happened in December 1845:

“Dear Brethren, I am truly happy to meet with you on British soil, where I am not known by the color of my skin, but where the Government knows me as a man. But I am free from American slavery, after wearing the galling chains on my limbs 53 years, 9 of which it has been my unhappy lot to be the slave of Henry Clay. It has been said by some, that Clay’s slaves had rather live with him than be free, but I had rather this day, have a millstone tied to my neck, and be sunk to the bottom of Detroit river, than to go back to Ashland and be his slave for life.

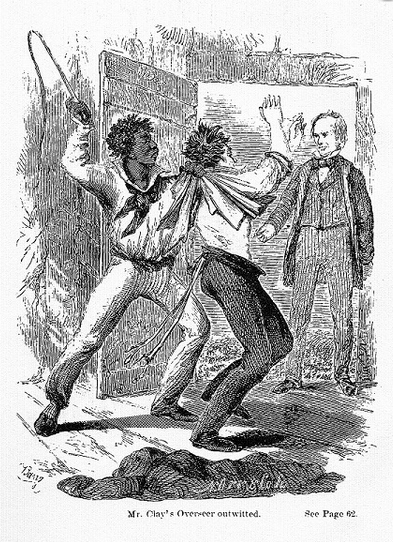

“As late as December 1845, Henry Clay had me stripped and tied up, and one hundred and fifty lashes given me on my naked back: the crime for which I was so abused was, I failed to return home on a visit to see my wife, on Monday morning, before 5 o’clock. My wife was living on another place, 3 miles from Ashland.

“During the 9 years living with Mr. Clay, he has not given me a hat nor cap to wear, nor a stitch of bed clothes, except one small coarse blanket. Yet he has said publicly his slaves were “fat and slick!” But I say if they are, it is not because they are so well used by him. They have nothing but coarse bread and meat to eat, and not enough of that. They are allowanced every week. For each field hand is allowed one peck of coarse corn meal and meat in proportion, and no vegetables of any kind. Such is the treatment that Henry Clay’s slaves receive from him.

“I can truly say that I have only one thing to lament over, and that is my bereft wife who is yet in bondage. If I only had her with me I should be happy. Yet think not that I am unhappy. Think not that I regret the choice that I have made. I counted the cost before I started. Before I took leave of my wife, she wept over me, and dressed the wounds on my back caused by the lash. I then gave her the parting hand, and started for Canada. I expected to be pursued as a felon, as I had been before, and to be hunted as a fox from mountain to cave. I well knew if I continued much longer with Clay, that I should be killed by such floggings and abuse by his cruel overseer in my old age. I wanted to be free before I died–and if I should be caught on the way to Canada and taken back, it could but be death, and I might as well die with the colic as the fever. With these considerations I started for Canada.

“Such usage as this caused me to flee from under the American eagle, and take shelter under the British crown. Thanks be to Heaven that I have got here at last: on yonder side of Detroit river, I was recognized as property; but on this side I am on free soil. Hail, Britannia! Shame, America! A Republican despotism [is] holding three millions of our fellow men in slavery. Oh what a contrast between slavery and liberty! Here I stand erect, without a chain upon my limbs. Redeemed, emancipated, by the generosity of Great Britain.

“I now feel as independent as ever Henry Clay felt when he was running for the White House. In fact I feel better. He has been defeated four or five times, and I but once. But he was running for slavery, and I for liberty. I think I have beat him out of sight. Thanks be to God that I am elected to Canada, and if I don’t live but one night, I am determined to die on free soil. Let my days be few or many, let me die sooner or later, my grave shall be made in free soil.”

The two tours of Ashland

Not long ago I read Clint Smith’s How The Word Is Passed: A Reckoning With The History of Slavery Across America. The author visited numerous monuments and historic landmarks to look at how slavery is remembered and presented to the public. He wrote about seven unique sites — from New York City’s Wall Street to Jefferson’s Monticello — their only shared characteristic being a direct involvement with slavery. Some attempt to tell their story openly and truthfully. For others, the subject is obfuscated and barely mentioned. At the slave labor camp known as Ashland, how is Henry Clay’s involvement with slavery remembered and presented to visitors?

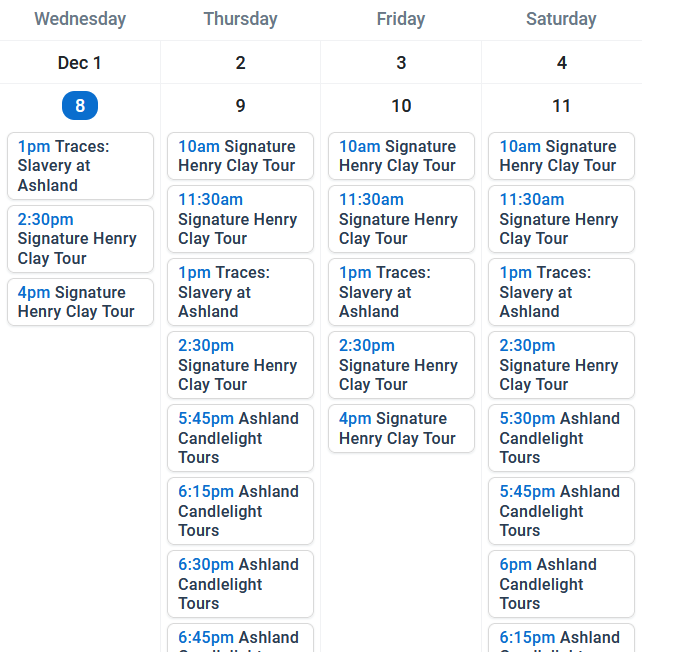

First, there are two separate tours offered, each $25, the “Signature Henry Clay Tour,” which runs four times a day when the slave labor camp known as Ashland is open to the public, and then a recently created, separate tour called “Traces: Slavery at Ashland,” which is offered once a day at the same time as the Signature tour.

The “Traces” tour comes with a warning, “This tour contains difficult information including discussions of sexual exploitation and other forms of violence. Parental discretion is advised,” while the “Signature” tour contains no warning about the historical whitewashing of Henry Clay vis-a-vis slavery — he’s purified and excused by an absence of discussion and materials about his crimes against humanity.

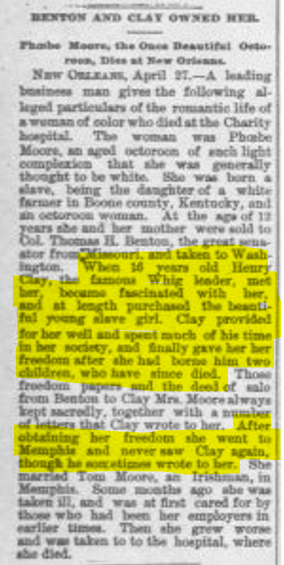

The Signature Tour is silent about Clay beating Mr. Richardson. Nothing is said about Clay’s purchase and repeated rape of an enslaved, sixteen- years-old girl, Phoebe Moore, keeping her with him as an enslaved concubine while in Washington (she had two children by Henry Clay). The Signature Tour says nothing about an enslaved man who committed suicide at the slave labor camp known as Ashland as a final act of desperation. The Signature Tour says not a word about the content of Mr. Richardson’s speech and his statement that he would rather drown in the Detroit River than be returned to the slave labor camp known Ashland.

The Signature Tour fails to acknowledge that the wealth that accrued to Clay was created by the labor of enslaved people and, when it benefitted him, their sale. The Signature Tour says nothing about Clay equating enslaved people as tangible property (along with his livestock, a cane, furniture, and gewgaws) to be passed along to his wife and heirs in his will. Put simply, the Signature Tour is comparatively silent about slavery.

Instead, what you hear is endless descriptions about the furnishings and their relation to Clay and his white children and white ancestors, his various roles as a career politician, and gushing, fan-boy praise, such as “His career was all about public service, about compromise, and keeping the Union together!”, or “Henry Clay was, you know, bigger than a rock star of his generation!”

How is the word passed on the “Traces of Slavery” tour? What a visitor immediately receives is an almost whispered statement by the guide that this tour will focus on “the other half” of Henry Clay, and that some of what the visitor will hear “may be upsetting.” The other half? Is it possible for a person to be a good, decent, moral person and an exemplary statesman while simultaneously an enslaver and rapist? Is such a neat dichotomy possible?

The story that is told of the 120 enslaved people who lived at the slave labor camp known as Ashland begins with a guide saying that but for Henry Clay’s enslaved valet, his enslaved wife, their enslaved children, and a few other enslaved people owned by Clay, almost nothing is known about the specifics of their existence. Even their surnames are unknown, and their given names are known only as how they are referred to in Clay’s correspondence, his will, and the records that survive from Ashland. A hedgerow lining a formal garden now stands where their rudimentary living quarters are speculated to have been; an eroded path marks one of the farm roads they would have follow to and from fields; a rebuilt smokehouse is shown to visitors, and in one corner there is mention of the hemp crops they would have grown and harvested.

Visitors are told that Henry Clay’s wife caught her husband raping an enslaved girl in a chicken coop, and that there were other children born to enslaved women at Ashland who were “mulattos” (persons not “purely white”) or who had the given name “Henry.” Mention is made of Phoebe Moore, who “attracted Henry Clay’s attention when she was twelve” and whom he later purchased and had “intimate relations” (a.k.a. rape). A tape of an actor reading Lewis Richardson’s speech is played. Visitors are taken into the mansion to gawk at the dining room table where enslaved people attended and a child’s nursery where Clay’s issue were cared for by enslaved women.

The lives of over 120 enslaved people of multiple generations spanning over a half century is encapsulated in 45 minutes.

What should be done?

What should be done at the slave labor camp known as Ashland? How to begin to solve our Ashland problem? I am not an historian and I know nothing of best practices for curating an historical site whose most salient feature is crimes against humanity, but I think that telling the truth about what transpired should always and forever be its teleology. The slave labor camp known as Ashland is backwards in its focus. I have a few ideas about how to begin to correct it.

First and foremost, the enslaved people at the slave labor camp known as Ashland should be the central focus of exhibits, tours, and materials rather than the enslaver and his family who inherited, bought, brutalized, profited from, and sold the enslaved. From the Clay shrine’s own records, over 120 people were enslaved and brutalized at Ashland. They were not passive objects but subjects who lived unique lives while held in an inhumane condition. They should be prominent at Ashland, not Clay and his family, and the culture and identity they created should be explored and told as well as their lived inhumane cruelty of their everyday life.

To do so, I suggest that an historian, cultural anthropologist, or similar experts who specialize in the area of 19th century American slavery, – persons similar to Ibrahima Seck, Director of Research, Whitney Plantation, Louisiana — should be placed in charge of curating and telling the story of the enslaver Henry Clay and the slave labor camp known as Ashland. The overarching charge should be to change the Clay shrine to a testament to those enslaved, and the entire site should be reworked to explain and inform visitors about exactly what transpired, why it was done, and how it was enabled and justified.

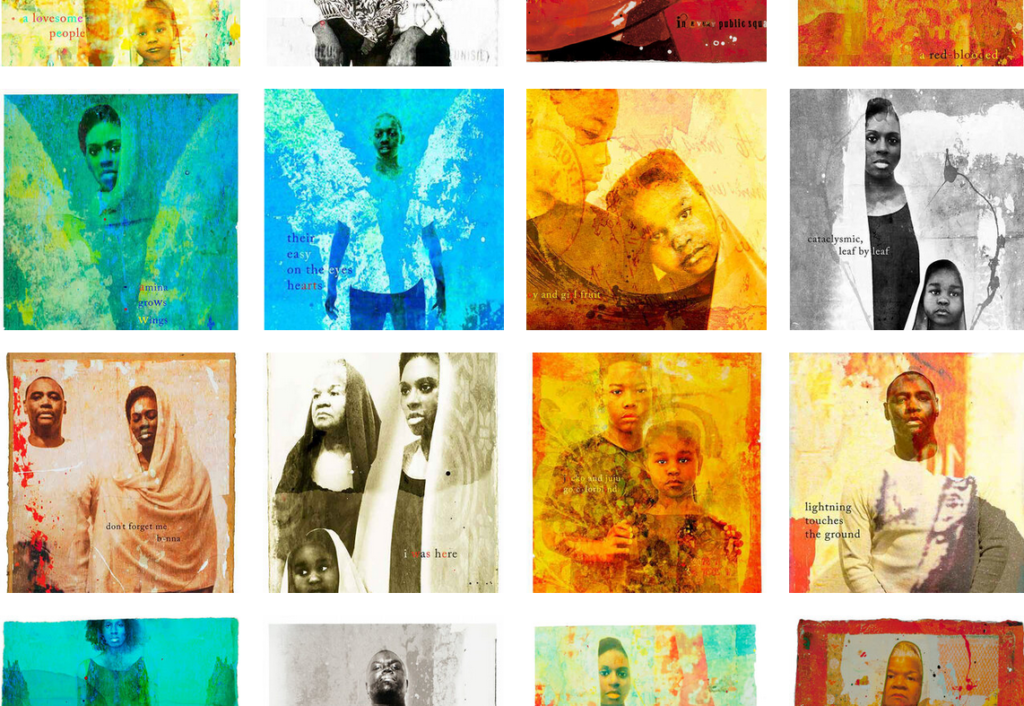

It is said that records and images of those enslaved by Henry Clay are all but nonexistent, that only “traces” of their lives remain, and that is often used as an excuse for comparative silence. That is an emblematic feature of slavery and should not be used to lessen their reality. For example, have you walked through downtown Lexington and seen in so many windows the silk-screened images of Black people looking back from windows and doorways? Actors were asked to imagine themselves as their ancestors sold at the slave auctions that took place at Cheapside, and photographs of them were printed on the screens that are behind the windows.

Perhaps a similar project could be placed at the slave labor camp known as Ashland — one-hundred and twenty life-size printed screens placed throughout the Clay shrine — in windows, doorways, halls, in the gardens and hanging from trees, in the Gingko Tree Cafe, in the gift shop, and as backdrops to the weddings, parties, and concerts that take place throughout the grounds so that everywhere visitors look, they would see ghost-like images representing those who were purchased, sold, lived, and died for the sole benefit of the enslaver Henry Clay and his issue.

As the Whitney Plantation, Louisiana, created a sculpture garden to commemorate and honor enslaved children who died in bondage at the site, so too should a memorial cemetery be created at the slave labor camp known as Ashland, perhaps on the front lawn so that those passing by would always and forever be reminded that enslaved people lived, were brutalized, and died to create the mansion standing behind. Everyone who has lived in Lexington for even a short time cannot avoid being aware that the Lexington Cemetery is home to Henry Clay’s mausoleum, which forms the base for the largest, tallest, most embarrassingly ostentatious monument in Central Kentucky — a 120-foot Corinthian column with a statue of the enslaver Clay perched on top, not surprisingly facing due south.

But where are the graves honoring the enslaved who died while held in bondage by Clay? This is an historical wrong that should be corrected.

The current board of directors of the slave labor camp called Ashland should be dismissed and replaced by Black people and those who have a demonstrated commitment to telling the truth about the institution of slavery in America and its multifaceted vestiges and expressions. I have no idea of the racial categories of all the board members, but it certainly appears that most if indeed not all are white people; further, given that they have countenanced and supported the ways in which the enslaved labor camp known as Ashland fails in its entirety to tell the truths about what transpired, that in itself is cause for the board to be replaced in toto. I have a greater trust that the descendants of the enslaved would be more focused on those such as Lewis Richardson, Phoebe Moore, and the one-hundred and twenty of those owned by Henry Clay rather than on the enslaver himself.

The weddings, galas, lawn parties, and music concerts that take place at the slave labor camp known as Ashland should immediately stop. They are garish and repulsive. For the same reasons that weddings, parties, and concerts are not held at sites of incredible brutality, torture, and death, the manager and board of directors should forever prohibit these events.

Finally, the Clay shrine often seems to exist as if it is somehow separate from the neighborhood and section of Lexington where it is located and somehow frozen in time and space. But it’s not — as we have been taught since elementary school, history lives and resonates through our political, cultural, economic, and social institutions and practices. The story told by the Clay shrine says nothing whatsoever about its place in Lexington in the aftermath of the Civil War and the dismantling of Reconstruction, during the Great Migration and the Jim Crow era, and across the 1960’s Civil Rights movement.

The slave labor camp known as Ashland is located in Lexington’s richest and most exclusive enclave, and the story of slavery, de jure and de facto segregation in housing and education – in all aspects of public life — should be an integral part of its mission. Discussion should broach topics such as how Henry Clay High School remained segregated until the mid-1960s, census data should be used to show how the neighborhoods surrounding Ashland have remained almost exclusively white, and other topics related to segregation and discrimination should be made transparent.

Put simply, the racism and segregation embraced and trumpeted by Henry Clay continues as a very serious, on-going problem today, and evidence of such can readily be found in the ways the word is currently passed at the slave labor camp known as Ashland.

Ky'im Yasharahla

I Am A Decendant From Henry Clay The Stateman And Yes A So Called Black Woman. Growing Up Eye Would Often Hear His Name Come Up, Its Shameful And Disgusting …

New Jawn

“The Ethicist.” New York Times Magazine, Dec. 28, 2021.

A friend’s daughter has sent my family an invitation to her upcoming “Plantation Wedding” in a Southern city. I had been looking forward to attending until I became aware of the appalling and tragic history of this estate and gardens. I am deeply troubled by the thought of celebrating on the grounds where hundreds of men, women and children were bought and sold, enslaved and tortured, so that white people can enjoy the privilege of a fairy-tale wedding.

Some friends are attending to support the mother of the bride. They urge me to just go and raise my own consciousness by touring the estate’s historical slave quarters and other sites in this city. I am skeptical that this is enough. I doubt I would be able to avoid speaking out during the wedding reception. Should I explain to the bride and groom the reason for my absence? She surely knows the estate’s history already. I foresee that all this will cause a rift in our families for some time. Would a donation to a historically Black college, in lieu of a wedding gift be appropriate?

Everyone in this scenario is white, raised in the Northeast and college-educated, and I’m astonished that they don’t realize this is a terrible idea. I want to act in good conscience and not create more disturbance. Do you have any thoughts? Name Withheld

[Reply]

In choosing a plantation wedding, this couple would appear to be idealizing lifestyles built directly on the unpaid labor of Black people who were treated as property and regularly abused. You regard that history with repugnance, and no doubt your friends would say they share that sentiment. But two decades into the 21st century, a couple planning a wedding would almost have to have gone out of their way not to see the connection. Evidently, they’ve tuned out a vigorous national discussion about the legacy of slavery; ignored much of what comes up if you simply type “plantation wedding” into Google; and achieved a serene obliviousness that normally requires the sort of monastic seclusion not associated with marriage.

Of course, there are all sorts of reasons that couples may choose a plantation setting for their wedding, but it doesn’t sound as if (like certain Black couples) they are seeking to subvert a racial hierarchy or to spend time amid the slave dwellings as a foray toward repair or education. Possibly, the couple haven’t given thought to how their Black guests would feel about the destination; possibly, there are no such guests. Either way, you can’t happily attend an event that takes place in what you understand to be an architectural adjunct to slavery.

You’re thinking about making a donation to a historically Black college in lieu of a gift. Perhaps the gesture is meant to assuage your guilt — akin to buying a carbon offset. It might be a good thing to make such a donation, but not for this reason. Or perhaps the donation is meant to send a message. But then you might as well tell them the truth: You’re pained you won’t be able to join them, but you can’t reconcile yourself to a celebration on these haunted grounds.

You rightly don’t want to find yourself bemoaning the venue of a wedding while you’re attending it and spoiling the special day for the couple. If you offer some innocuous excuse for your absence, however, you’ll only be protecting your own sense of moral purity. That’s why the braver, better path is to explain, well in advance, why you won’t be there. The exchange will be uncomfortable. But if our country is going to get out from under four centuries of racism, uncomfortable moments can’t be avoided. You may be accused of getting on a high horse. So be it. Those saddled on high horses sometimes see the fields more clearly than others.