By John Hennen

Everyone understands the importance of music to social movements, and no song of working-class justice is more widely known than “Which Side Are You On?” written by Florence Reece in 1931. Florence was embroiled in the 1931 Eastern Kentucky coal strike, when thousands of Harlan and Bell county coal miners struggled for survival against local coal operators and law enforcement. Florence performed her masterpiece hundreds of times in the next half-century and never failed to inspire the spirit of militant resistance to economic, social, and political oppression.

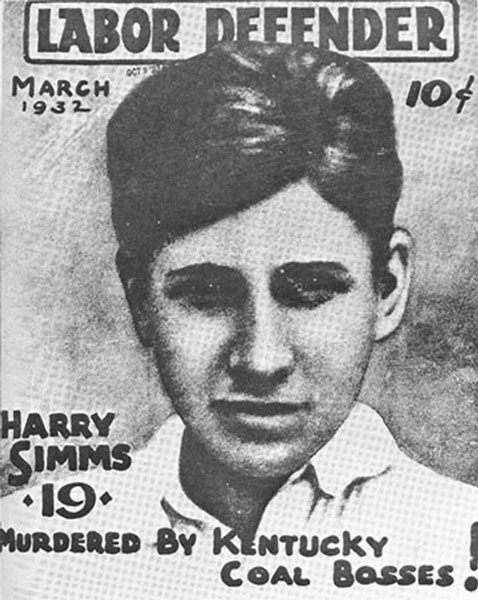

Radical actions, radical reporting: Harry Simms was a 19-year old organizer for the National Miners Union who was assassinated by Knox County deputies in February 1932. His murder was a front cover story for the Labor Defender, a now-defunct radical labor magazine from the 1920s and 1930s.

Many may not realize, however, that the organized resistance to the “gun thugs of J. H. Blair” during the 1931-1932 Harlan and Bell county mine war was led not by the United Mine Workers of America, but by a competing radical alternative to the UMWA, the National Miners Union. Convinced by the Great Depression that capitalism was on the road to extinction, the NMU rejected the capitalist accommodation practiced by the American Federation of Labor and the UMWA. Instead it promoted a radical vision of social revolution, class solidarity, and workers’ control of the means of production.

When the Black Mountain Coal Company imposed a ten percent wage cut in February 1931, hundreds of Harlan County miners walked out to protest the latest in a litany of unsafe, unfair, and penurious practices by the company. Already suffering from short hours, earlier pay cuts, arbitrary firings, threats, and layoffs, strikers apparently decided it was better, as one allegedly said, to starve on strike rather than at work. Strike leaders, many of them veterans of a 1922 strike supported by the United Mine Workers, turned again to the UMWA for help.

But the failed 1922 strike, and the ensuing years fighting legal and political offensives against unionization in the Appalachian coal fields, had practically destroyed the UMWA. When the 1931 strike began, UMWA vice-president Philip Murray welcomed the potential influx of new members but, following a massive and militant Bell County rally sponsored by the UMWA, Murray lost his initial enthusiasm. He and union president John L. Lewis concluded that the independent mobilization of the Harlan and Bell strikers reflected the type of radical independence—anathema to Lewis—that would undermine union discipline. The union’s commitment to financial and material support in the form of food and milk for striking families evaporated just as the action spread to twenty-three Harlan and Bell county operations with nearly 6,000 miners. When the UMWA pulled out, the strike’s momentum collapsed and the strikers and their families were left without work, income, or prospects.

Into the void left by the UMWA came the National Miners Union. The NMU was the American Communist Party’s radical challenge to the conservative UMWA, founded during the Party’s so-called “third period” that began in 1927. The “third period” represented a change from American Communism’s traditional tactic of “boring from within” established trade unions in order to seize control of the labor movement. The NMU was founded as a “dual union” to compete with, rather than influence, the UMWA. Local civic leaders in Harlan and Bell were exponentially more fearful of the NMU than the “bread and butter” unionism of John L. Lewis. To discredit the more radical union, they focused on its “alien” leadership, despite the fact that Eastern Kentucky Holiness preachers Jim Grace and Finley Donaldson, along with Andrew Ogan and Sam Reece, reflected indigenous leadership within the Kentucky NMU.

Resistance is a family affair

Reece, a veteran local organizer dating back to the 1922 strike and a longtime dissident within the UMWA, was targeted for special attention by the Harlan County Coal Operators Association. After a violent battle between strikers and deputies at Evarts in May 1931, Sam and Florence Reece’s home was raided by Sheriff Blair’s deputies. “When the thugs were raiding our house off and on,” Florence Reece recalled, “and Sam was run off, I felt like I just had to do something to help.” The result was “Which Side Are You On,” perhaps the most popular and enduring anthem of the labor movement down to this day.

It was logical for Sam Reece to work with the NMU once the UMWA pulled its support from the strike. The NMU sponsored soup kitchens for starving families when the local Red Cross, pressured by the Operators Association, withheld assistance from striking families. The ideological posture of the American Communist Party—whose insistence on racial equality and, more importantly, embrace of atheism later alienated many of its original supporters—initially was of little concern to the hungry.

By early 1932 the Harlan-Bell strike failed, and soon the Communist Party’s dual union idea was abandoned. Many of the NMU’s most committed radical organizers rejoined the conventional trade union movement and soon invigorated the mass mobilization of industrial labor that swept the country by 1934. Working-class militancy forced the reform administration of Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt to support a new institutional framework, represented by the Wagner Act of 1935, which established systematic protection for the right of workers to organize and bargain collectively. Mobilized in part by former NMU radicals within the new Committee on Industrial Organization (later the Congress of Industrial Organizations), the UMWA re-entered the Eastern Kentucky fields by 1936 and, with the protection of Wagner, grew rapidly. In a sense, then, Eastern Kentucky fighters like Sam and Florence Reece, and the radical leftists of the NMU, laid the foundation for the American middle class.

A much-expanded version of this essay was published as an introduction to Harlan Miners Speak: Report on Terrorism in the Kentucky Coal Fields, a reissue of the 1932 report put out by the University Press of Kentucky in 2008. The author suggests that interested readers also take a look at David C. Duke’s Writers and Miners: Activism and Imagery in America, and Alan Banks, “Miners Talk Back: Labor Activism in Southeastern Kentucky in 1922,” which appears in Confronting Appalchian Stereotypes: Back Talk from an American Region. Pick up copies at Morris Book Shop or the Wild Fig Book Shop.

Karl Marx

Man, I really am a moron.

G.V.Kucewicz

In the 1970’s I was doing oral labor history grad work ,I met with Miriam Bloom , a Springfield Mass YCL member in the 1920-30’s Harry Simms (Heresh sp?) ,was her cousin ,I was told by her that after his murder by Harlan County Coal Thugs ,his body was received in Springfield ,Mass,by a crowd of thousands,and he was buried at the West Springfield Jewish Cemetery ,and as far as I know ,there he still sleeps with the ages .

Norm Goldie

Thanks so much for enlightening me of the strife felt in the early twentieth century and the radicalism shown by those in Harlan and Bell counties.

I spent, all told about two years, working on reclamation sites (this was the mid-80’s when there was money available for reclamation) and was run off by one landowner after the other. I was mistaken many times as a coal operator ‘goon” sent there to destroy even more of the land and water. When the opposite was true.

Today it’s Blair mountain, tomorrow the whole eastern part of our state (Kentucky) and the southwestern portion of West Virginia will be flattened.

I once did a site in Pike county that had only one point of reference, that being a survey control point saved by the coal company for future work. The rest of the land was flattened and had taken on the look of a moonscape. The maps I had showed no resemblence to the devastation created by the surface mining.

I spent many days around Evarts, and the forks of the Upper Cumberland river, including Poor fork.

Man, I love reading this stuff. Keep it coming. You have my e-mail address.

Norman E. Goldie, Jr.

208 Green Hill Way

Mount sterling, Ky 40353