Sodomy laws and marriage amendments

By Marcus Flores

North Carolina put to vote a heterosexual marriage referendum in early May of this year. Given the state’s rural demographics, perhaps the result was an unsurprising one. Yet it was not the first (and probably will not be the last) state to do so; in 2004 Kentucky adopted a similar such amendment from a resolution that cited the Lawrence v. Texas Supreme Court case, which, the resolution said, “may undermine the foundation of marriage as the fundamental union between a man and a woman.” Strange.

Lawrence v. Texas concerned “deviate sexual intercourse”—sodomy—between consenting adults. In 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court axed Texas’s sodomy laws and ipso facto those of all states. The decision had about as much to do with marriage as did Kentucky’s 1992 Supreme Court Case that also shot down the state’s sodomy laws. In Kentucky v. Wasson, the male defendant, Jeffrey Wasson, was charged for soliciting sex from an undercover police officer (this was apparently not uncommon). The arguments of the case refer to the “moving stream,” an analogy for the accumulation of precedents in which 25 states had recently rescinded their own sodomy laws. In short, the occasion was ripe for Kentucky to undam itself.

It strikes many a citizen to learn that their own state had or still has sodomy laws, and the question as to their origin, at least in the United States, is likewise curious. Since the term itself etymologically begins with the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, it must follow from religious condemnation of dishonorable desires, which Henry VIII codified following a split with the Catholic Church. American colonists, often romantically described as seeking a haven for religious freedoms, imported these same restrictions. In 1683, Pennsylvania law categorized sodomy as an “unnatural sin.” (Mind you, there was no official separation of church and state.)

Among the other provisions of Kentucky’s marriage resolution, which petitioned “the United States Congress to propose an amendment to the Constitution of the United States,” are the following selections:

That “marriage is both a solemn civil and religious ceremony.”

That marriage is “the highest and most blessed of relationships.”

That the state recognize the “sacrament of marriage as the union of a man and a woman.”

That “the union of man and woman in marriage has been recognized as the foundation of society since the beginning of time.” (All italics mine)

In other words, the resolution is replete with religious confetti and undergirded by the premise that heterosexual marriage confers special benefits upon its participants. Moreover, it celebrates the “merger of two sentinent [sic] beings into one.” This none-too-subtle approach is not the language of legislature but rather the solicitation of scripture where it is not permitted.

A ceremony ought not be both civil and religious because it would necessarily entangle the two. The bill’s further reasoning builds on this blurring of spheres: pompous platitudes elevate the act of marriage to a symbol of superiority, and a religious one to boot. (May I also ask when it was that sacraments were admitted to a supposedly secular code of laws?) If that fails to give some secularists cardiovascular trouble, then this fourth and final provision certainly will not. The endorsement of a specific religion in the bill is as subtle as it as dangerous. Don’t see it? Look again. Only in certain religious worldviews do time and society begin simultaneously. Secular knowledge—what should form the very kernel of legislation—indicates that dinosaurs existed long before marriage.

The Kentucky referendum was approved by over 70 percent. Section 233A of the Kentucky Constitution now reads: “Only a marriage between one man and one woman shall be valid or recognized as a marriage in Kentucky. A legal status identical or substantially similar to that of marriage for unmarried individuals shall not be valid or recognized.” Meanwhile, around 10 other states have gone on to legalize homosexual marriage, and some even permit civil unions (any hope for the latter was also sunk by 233A). Still, the alarmingly high number of states that have marriage definition amendments in their constitutions suggests a response to the burgeoning marriage equity movement. It is an effort to slow the stream that will ultimately flow freely.

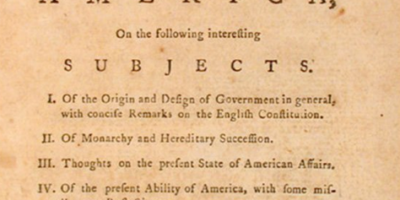

Though it took until 2003 for consensual sex among homosexuals to be entirely legal, a wild card may accelerate the process for marriage. Contrary to president Obama’s belief, same sex marriage is not simply a states’ rights issue. If a New York gay couple relocates to Kentucky, what happens to their rights? According to KRS 402.040, they dissolve. Given enough disputes, the U. S. Supreme Court will have to intervene. And in a few years, when same sex marriage prohibition seems as distant Henry VIII, Thomas Paine’s sage words will be most relevant: time makes more converts than reason.

Leave a Reply