A post-navigational meander

By Wesley Houp

Cross-currents

On the morning of May 5, 2010, the Dixie Belle, a sternwheeler owned and operated by Shaker Village in Mercer Co., broke free of its moorings on the Kentucky River near High Bridge after being struck by a large concrete dock and other flood debris. The 20 ton, 65-foot, 100-passenger boat traveled downstream on the swollen Kentucky, passing safely over Lock and Dam #7 before rescuers eventually corralled it to the bank just above Brooklyn Bridge on state highway 68, where it held sway against the current as the river crested at 42 feet, approximately ten feet above flood stage, its highest point since 1978.

After several weeks the Dixie Belle was eventually pulled from the water several more miles downstream at Cummins Marina, where it was later inspected by the U.S. Coast Guard. Found structurally sound, the flood-stranded craft was partially dismantled and finally hauled overland, no small task given the extremely steep, narrow, and winding roads in and out of the river valley, not to mention the hilly, curvy roads through the Bluegrass Region atop the palisades. The thirty or so mile trip took two days, and the Dixie Belle once again rested its weight in the Kentucky near Camp Nelson, seventeen or so miles upstream from its home.

The Belle‘s remarkable trip over Lock 7 illustrates two cross-current storylines for the present-day Kentucky River. The first line we know quite well: nature, without advanced warning, trumps the hand of man. No matter what objects and obstacles we stack in front, the river will make way. The fact that our river has, for the past century, been segmented by locks and dams has also helped to regionalize (sectionalize) further the damage flooding does: “It’s those people down in Valley View, High Bridge, or Frankfort that need FEMA, not us.”

The second story is much more contemporary: the Army Corps of Engineers’ and now The Kentucky River Authority’s “selective discontinuation” and “cut-off” of the locks along most of the Kentucky’s 255 miles, a process initiated in the late 90s, has created, in effect, isolated, slow moving segments, each with its own unique riverscape and, depending on accessibility, patterns of use. In a post-navigational existence, it takes the force of a catastrophic flood to remind us that the river is one continuous ribbon of life running from the mountains of Eastern Kentucky to the Ohio. Had Lock #7 been functional, the ride home for the Dixie Belle would have taken no more than an hour.

The fact that the boat had to be transported overland is not the issue of interest, though. Of far greater interest is how closing and sealing off the locks has affected people’s interaction with and perception of the river is. While it is true that the locks have always promoted a sense of isolationism and boundary among those “river rats” living along the banks, the reality is that each pool truly is isolated. If you want to experience the river in its entirety today, you will have to paddle; only a canoe or kayak can be portaged around the massive, aging concrete structures—and only with much difficulty as the terrain along most of the river’s length is steep and unforgiving, covered with stinging nettles by summer, scoured and caked in slippery mud by winter.

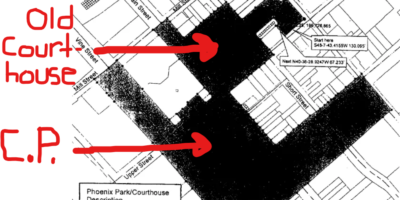

Slack water

On a Friday morning several weeks after the flood-waters have crested, some friends and I put in our kayaks and canoes below Lock #7, on a two-night search for the Dixie Belle. Though successive rains since the flood have slowed the water’s recession, the river is still running high. The raging current that scoured away large trees and boulders across the river below the lock has left the beach on the Jessamine Co. side untouched, even enhanced with fresh sand. The approach to the beach, our put-in, is steep; we first haul down the gear and, later, lower the boats methodically to the river’s edge. The water, still up several feet, still runs fast for the otherwise sluggish Kentucky.

In Engineering the Kentucky River: The Commonwealth’s Waterway, Leland R. Johnson and Charles E. Parrish talk about the “spectacular flight” of Captain Harry Todd’s Blue Wing during the flood of 1846. The Richmond Chronicle poeticized how the steamer “skimmed like a bird over the waters, and its beautiful prow cleaved its foamy track through the angry tide… The inhabitants stand aghast. The fire breathing monster is among them. The thundering of his loud bellow is heard far echoing along the shore.” The Blue Wing‘s historic trip up to Irvine rallied, once again, popular interest and support for extending what was known as the “Kentucky River Slack Water Project”—an early “plan for curbing the unruly Kentucky and transforming it into a placid servant of Bluegrass commerce.”

Also in 1846, the city of Richmond played host to a “Slack Water Navigation Convention” with delegates from nine counties adjacent the river, all considering how the river’s fluctuating water levels might be raised and smoothed, a sort of riverine ritalin to improve commerce from the state’s eastern innards to ports along the Ohio and Mississippi. The convention title sounds dim-witted, almost vulgar to 21st century ears, but the project was a reliable source of revenue for the state treasury in the pre-Corps days of the Kentucky, each slack water dam exacting a toll on passing craft and allowing Kentucky cargo, by way of New Orleans ports, entryway into nineteenth century global markets.

A war with Mexico would help spell the end of the project but only for a time. The opening up of the eastern coalfields and the buying up of riverfront properties, particularly in the upper stretches, by Lexington businessmen would convince the state government, once and for all, of the economic efficacy of full scale impoundment. And in a strange twist of fate, the state’s decision to follow through on this commitment would, 150 or so years later prevent the Dixie Belle from making its own heroic flight up the flooded channel—this time to save itself.

The first stone in Lock #7 was lowered into place on August 4, 1896 and the lock opened for traffic on December 11, 1897. I’ve seen photographs of steam-powered derricks assembling the massive walls, raising and lowering booms like spiny insects working over a symmetrical hive, men, like ants, scurrying across the face of cut stones. In one photo, a man raises a hand to greet the block and tackle. It might be Nelson or Grant Horn, two ancestors of mine who poured their sweat through the sieve of modern progress. High Bridge and Lock #7 have, from the onset, been family affairs. In the decades following Lock #7’s completion, my ancestors, like most other residents in towns up and down the Kentucky would find work, pleasure, and rejuvenation in the rising slack water pools, none more so than my great-grandfather, Wes, who’s dancing feats on the Falls City II, an Ohio river-based steamer which plied from Louisville all the way to Valley View, have passed into lore. He was a thin, happy barber by trade and a dapper dandy in soft shoe by recreation, a swinging gal on each arm.

High Bridge to Brooklyn Bridge

But swinging gals are the last things that come to mind in the post-diluvial riverscape of 2010. We enter the current with low voices and no fanfare. It’s a quick float two miles to the mouth of Minter’s Branch, a nameless capillary on our navigational charts but a key landmark for me nonetheless. Minter’s Branch, locally dubbed for some earlier homesteaders at its headwater springs, cuts a deep, narrow gorge that marks the northern boundary of the farm my father sharecropped for 30 plus years. It’s the wooded, rocky, severe ground where I learned the basics of how to build a life—hammer a nail, turn a wheel, file a blade, make meaningful marks in the wood, in the soil, and above all, heed the river that’s been grinding past for more than 100 million years.

The first hour on the water is, arguably, the best, each paddler feeling his craft’s response to the current situation and rediscovering the precise energy needed to maintain his measured isolation from the group. Minter’s, at normal pool level, presents a shady towhead, well-suited for deadline fishing and wiling away the heat of a summer day. With the water up a few feet and the current pronounced, the towhead forms a riffle, blockaded by the bare length of a deadfall, a perfect corral. We wade in the cool water, and I cast a night-crawler in the upstream eddy of the towhead. More than fishing, we’re killing time, giving the rest of our party who couldn’t make the early put-in a better chance to catch us later in the afternoon. But after three hours and with several bass and a drum on the stringer, we push off and maintain a slow pace, thinking our comrades will surely overtake us by Brooklyn. The bridge at the small community of Brooklyn is the antithesis of its larger, northern namesake. Its molded concrete expanse was designed for expediency of assemblage, leaving its cumulative aesthetic impact so thoroughly underwhelming that beholding it from a kayak is on par with beholding a Wal-Mart parking lot from an airplane.

Waiting on Shawnee Run

After consultation with our river map, a packet of old barge maps re-tooled for our purposes, we identify two possible campsites, Shawnee or Rocky Runs, both creeks conjoining the mainstream about mid-point on our 20-mile float. The afternoon wears on, and there’s still no sign of our rear-guard. Around 6pm we enter the mouth of Shawnee Run, a substantial and serpentine tributary that drains, among other land, the Shaker’s historic village at Pleasant Hill. This stretch is steeped in mineral history: above the stream’s mouth, an abandoned calcite mine, and across the river, several old fluorspar mines were once operated by the Chinn Mineral Company. The old Chinn homestead looms through the trees on the Woodford Co. side at Mundy’s Landing, immediately downstream from Shawnee Run. William Ellis, in The Kentucky River, mentions Chinn’s mineral operation, which relied on the river for transport of fluorspar, used in making steel, and calcite, used in making putties, paints, and car tires. The vertical vein of calcite above Shawnee Run was “deposited by hydrothermal fluids moving upward along fractures and faults,” and the Chinn Company mined and then milled the mineral into a fine powder, known as “Spanish White,” shipped it up stream to High Bridge where it was conveyed up the cliff and loaded onto trains.

After losing close to four thousand dollars when a loaded barge sank near Mundy’s Landing 1920, the company’s days were numbered. With the impoundment of the river just barely complete, a century-long undertaking, local industries, like Chinn’s, were already disappearing. The slack water necessary for reliable transportation of goods finally filled the length of the Kentucky just in time for the railroad to render river-trade obsolete—an irony of modernist proportions.

We make camp above a sharp bend in the creek, deploy tents, start a fire and dinner, and wait. And wait. And wait. After a meal of river-rat mulligan stew (wild turkey breast, green onions, garlic, carrots, potatoes, kale) and several long pulls of Laphroaig quarter-cask, it’s lights out. Must be midnight. Just as we’re retiring to tents, a voice from below, barely audible over the babbling brook. A flash from a headlamp. Lyle and Gary emerge from the darkness with bedraggled, exhausted expressions. Reunited. But no one’s ecstatic, least of all them. They had to paddle three and a half miles against the current in the new-moon dark to find us.

Disconnection

After another day and night exploring Shawnee Run, we break camp. On a rainy Sunday morning we push on toward Lock #6, catching just enough break from the rain to float for a while below Cummin’s Falls, the precipitous end of Cummin’s Creek, which is, unfortunately, made much less spectacular by Cummin’s Marina, a long and largely empty dock and concrete block store with an adjacent RV park located on the Mercer Co. shore. With more rain, we decide to take out at Nonesuch Landing, just around the bend, six miles short of our intended destination. Just past the marina, though, obscured by the tree-lined shore, we catch our first glimpse of the Dixie Belle.

Under normal circumstances, seeing the Belle ply upstream under High Bridge and past the mouth of the Dix River (a scene I’ve witnessed more times than I can count), it’s possible to imagine an earlier era on the Kentucky, an age when “fire breathing monsters” awed the river-folk with their sheer size and potential, an age when river-travel was extended by locks and dams, not shut off by them.

Seeing such a boat in dry isolation, its vitality neutered, reminds me that the Belle is, after all, a theme-park ride, a floating Potemkin village. The unbecoming condition this “prop” seems to hide is the river’s fragmentation. The image of a riverboat decommissioned and partially dissembled might be an apt symbol for the Kentucky as long as most of us only experience it through a drinking glass or the end of a garden hose.

Leave a Reply