A river rat retrospective

By Wesley Houp

rheotaxis: the tendency of certain living things to move in response to the mechanical stimulus of a current of water.

“In terra incognita, if the opportunity presents itself at all, the only way to go is by river—always assuming, of course, that you and the river happen to have the same general route in mind and that the river doesn’t object violently to having passengers. At the same time, there is a certain comfort in knowing where the thing ends and where it begins.”

—John Madson, from Up on the River

“Life never grew stale or weary for him. To watch the river and talk about the river and recall old scenes and old stories about the river and snap up every line of news about the river and tell again his days and ways of love for the river—it was enough. Men wear out first in their spirits. No riverman’s spirit flagged so long as he could remember the river.”

—Charles Edward Russell, from A-Rafting on the Mississip’

As the son of two aquatic biologists, I spent a goodly portion of my childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood doubled-over in benthological awe, wading through riffles and pools with a kick-net or seine, eager to pick through the contents of each haul as if I were skimming off the top of some vast and foreign treasury answers to life’s perplexing questions that elude the hoi polloi, hung just beneath the current, disguised against rope-swinging day-trippers and stoic, bank-hushed fisher-boys as an insignificant detail of the larger set—creek cobble and riprap scoured black and tumbled smooth. From intermittent headwater streams to alluvial river mouths, I associate the life in and of the current with all that is good and all that is essential in the life gently but seriously fashioned for me by gentle and serious people.

In every place I’ve lived as an adult, from Pennsylvania to Tennessee, mapping out and connecting to watersheds has been not only a constant, sometimes obsessive, undertaking but an outright existential necessity. We all need water to survive, but some of us need it in more ways than one and seek it out wherever and whenever possible.

I’m not talking about recreational pleasure or sport although I’m not necessarily opposed to those activities, but a fascination more akin to the elemental “draw” Harland Hubbard notes in the opening lines of Shantyboat: “A river tugs at whatever is within reach, trying to set it afloat and carry it downstream… The river extends this power of drawing all things with it even to the imagination of those who live on its banks. Who can long watch the ceaseless lapsing of a river’s current without conceiving a desire to set himself adrift, and, like the driftwood which glides past, float with the stream clear to the final ocean?”

I’m talking about a real ontological need to experience—to feel—the water, its undercurrents and biota, be part of its course, and live, if only fleetingly and as best a gravity-dumb biped can, by the alternating and life-altering charges of rheotaxis.

Folk memory

There’s no two ways around it. The Kentucky River courses through the geography of first, second, third, and even fourth-hand memories that constitute my life. Had not my ancestors fallen on hard times, left East Tennessee in the 1850s for the big woods of Eastern Kentucky, logged the old growth timber in Breathitt and Clay Counties, and experienced firsthand the spring tides above the forks of the Kentucky, the splash- dammed tributaries, log-rafts, and the precarious, serpentine run to downstream sawmills, like the one that operated near present-day Lock 7, the magnetism of some other distant current might sing to me from my subconscious.

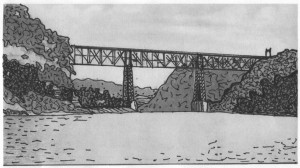

But as it were, lucky for me I’m certain, the Kentucky delivered my grizzled ancestors to High Bridge, a small but promising river and (after 1877) railroad town. This sleepy corner of central Kentucky, with its mammoth cantilevered bridge transecting the deep-set ribbon of life, remains for me, even still, home.

They had, no doubt, first encountered this part of the inner bluegrass in the years preceding the Civil War, and after serving in the Union Army through Perryville, Stones River, and Chickamauga, Edmund and Robert Houp (father and son), my fourth and third great grandfathers respectively, shunned the rugged hills and hollows of Breathitt for the loamy and forgiving earth of southwest Jessamine.

Sweetheart of the sawmill

At that time, the lock and dams extended only as far as Tyrone, some thirty-five miles downstream from High Bridge, and the river level was low enough to allow the Beckham family of Oregon Bend, Mercer County, to drive their ox-drawn wagons up the bottom, through riffle and shallow pool much of the way, till they converged on High Bridge, too, eventually setting up residence in one of the only houses in the river-bottom and putting into place another part of my ancestral equation.

As family lore would have it, when Haggie Mae Beckham (my father’s maternal grandmother) was a young lady, she gained some reputation among loggers and mill-workers for her ability to “fish out” runaway logs. The story involving Haggie Mae that my family knows best occurred sometime in the decade prior to WWI—the height of the timber boom and the era of mountain logmen and raftsmen on the Kentucky.

The legend has Haggie fishing out one fine length of white oak and bringing it to rest on the bank below her family’s house, across from the mouth of the Dix, where the valley bends to the north and the emboldened Kentucky immediately passes beneath the shadow of High Bridge. In the night log bandits made off with Haggie’s prize, most likely dehorning her crude mark, relegating her, as was most common in the era, to losers-weepers status. The river gives on occasion but takes away as a general course of habit.

Discovering her log was missing, Haggie scoured the log-jammed banks the next morning in search of her stolen windfall. What the bandits hadn’t considered was the extent to which this young female river-scruff had studied her prized length of white oak, and when she found the log unattended (and curiously nearby), she called on the help of some sawmill employees and managed to move the log upstream into the queue of logs waiting at the tramway, the giant wooden-framed, steam-powered conveyor belt that drew Eastern Kentucky’s bounty up and out of the river bottom, some three hundred feet, to Hugh’s sawmill atop the palisades in High Bridge.

Determined not to fall victim to bandits again, Haggie Mae guarded her log all the way to the base of the tramway, and when it was loaded, she jumped up, straddled the trunk, and rode the magnificent timber all the way to the top. Such antics were considered rare, not to mention foolish, among loggers, raftsmen, and sawmill workers alike, given the healthy respect these men held for heavy timber. Logs indiscriminately drowned men in the water and maimed them on the bank.

The sight of a girl riding a 16-foot white oak log up the narrow, steeply inclined tramway, careless of personal injury, must’ve cut a deep and humbling impression on all those who witnessed the scene: stay away from that girl, boys. She’s incredibly single-minded, purpose-driven, and more than likely insane. She delivered her log to the sawmill’s blade, and, as the story goes, received 18 dollars for her prize, though I’m inclined to think the real figure was something less.

River, brush, and bottle fever

From the Beckham’s house, it was just a short walk up the river-bottom to the large spring where the family drew their water. The path up the bottom was well worn, and where it met the stream below the spring, duck-boards provided a relatively clean crossing.

The image of Haggie Mae and her mother walking to the spring was preserved for posterity in the watercolors of Paul Sawyier, perhaps Kentucky’s most renowned impressionist painter. The Beckhams, along with many other nearby residents, came to know Sawyier in the years between 1910 and 1913, when he moored his houseboat at High Bridge, lived a reclusive life, obsessively whetting his life-long appetite for the river, his bottle fever pulling him steadily toward oblivion, his brushes pulling him crosswise to immortality.

When he completed “Going to the Spring,” he tried to sell it to Haggie’s mother, but she “had no use for it” and offered to feed him dinner instead out of real frontier sympathy for scroungers. I’m sure he accepted, and I’m sure he was used to the cool market-reception the fruits of his artistic labor regularly received from locals, in whom tendrils of frontier asceticism still girdled all sense of aesthetics, leaving only the dulled affect of necessity. But, as his body of work demonstrates, he was undaunted. The number of reproduced river-related Sawyier prints exceeds eighty. It stands to reason he produced hundreds of sketches, studies, and paintings, many of which probably never made it out of the river-bottom.

Local legend has it that after Sawyier vacated his houseboat and headed north to the Catskills, local kids ransacked the place, tossing countless paintings over the gunnels in favor of more precious bounty—crusty paint-knives, tobacco tins, a broken pocket watch, half a fifth of snake-oil whiskey, and the crown jewels, a little, rickety wood stove and enamelware kettle, prizes sure to impress even the dourest of hardscrabble mamas.

Grandpa was a “Winter” Shaker

By the first decade of the twentieth century, Robert Houp had sired a small army of children, mostly boys. The oldest, George Wesley (my first namesake), was raised by the Shakers at nearby Pleasant Hill. The decade after the Civil War must have been a hard one because many families in the area sent their kids (particularly those who were old enough to handle a hoe or swing an ax) to be cared for by the Shakers.

Since the Shakers were the real losers in the war between North and South (having been all but bankrupted by the indefatigable appetites of two “invading” armies), they were more than happy to welcome young, impressionable youths into the fold. Even adults availed themselves of the Shaker’s kindness and plenty, particularly in the winter months when sustenance was scarce. They were known in local parlance as “Winter Shakers” because as soon as the season turned and opportunity thawed, most abandoned their adoptive family, picking up life as they had left it the year before.

Always free to leave, the children were fed, clothed, and provided with shelter in exchange for the labor they contributed to the community. For obvious reasons, the Shakers held high hopes that some of their young wards would eschew the hardscrabble life and moral malaise of the secular world and adopt the agrarian (and in dogmatic irony unsustainable) Shaker way for good. Let’s call it a hedging of earthly bets doomed to come back snake-eyes.

George Wesley, like so many others, eventually found his way back down into the world of drunks, drifters and do-little river rats. He left the community, though, with a solid grasp of broom-craft and the art of cutting cedar shakes.

Boom and bust

While George Wesley went on to live as long and respectable a life as one could hope, his younger brother, Jackson, was not so lucky. At about the same time Haggie Mae was scouring the banks for unclaimed logs, and Paul Sawyier was setting the riverscape to canvas, Jackson Houp, like so many other young men, was trying to cash in on the timber boom. He would travel up-river as far as Beattyville and the forks, buying up logs from wherever and whomever he could, assembling his own rafts to float back down to High Bridge.

The number of rafts and successful floats he made is uncertain (it surely wasn’t very many), but we know each trip upstream and each attempt to assemble a profitable raft required significant expenditures of cash. A modest profit might be realized if everything went off without a hitch; one misstep, however, could sink your ass both literally and figuratively.

As usual, any economic boom simultaneously creates equal-opportunity piles of shit for the stepping, and as Jackson’s luck would have it, he found the king shit-pile. Sometime around 1910, a particularly nasty gang of felon log bandits made off downstream with a newly assembled raft, leaving Jackson high and dry for weeks of labor and a wad of dough. Riding the floodwaters and with a day’s lead, the bandits more than likely steered Jackson’s raft on past High Bridge to the mills in Frankfort and vanished into “Crawfish Bottom,” a seedier side of town, which, in the words of historian Thomas D. Clark, “clung to the famous river cliff like a half-drowned animal”—a place where men “could forget their trials and tribulations and give themselves over to at least one night of complete debauchery.”

Ruined, Jackson returned home, checked in on his mother and father, and was last seen walking up the river-bottom past the bridge. They found him the next afternoon, hanging by a length of leather strap from a cross-member in the rickety little barn just up the bank from the Kentucky’s swollen and muddy tide.

Leave a Reply