In July 2018, Lexington formally convened a task force to look into issues of neighborhood displacement. Chaired by First District Council Member James Brown (a realtor when not counciling), the Task Force is made up, the local ABC affiliate reports, “of Urban County Councilmembers, city developers, planners, historians, residents and other community members.” Below is a “citizen input” comment given by Danny Mayer at the September 4 meeting, the committee’s third, which was held at a local community college.

In July 2018, Lexington formally convened a task force to look into issues of neighborhood displacement. Chaired by First District Council Member James Brown (a realtor when not counciling), the Task Force is made up, the local ABC affiliate reports, “of Urban County Councilmembers, city developers, planners, historians, residents and other community members.” Below is a “citizen input” comment given by Danny Mayer at the September 4 meeting, the committee’s third, which was held at a local community college.

*****

Dear Committee,

I am a 10-year resident of what this Task Force may consider to be a “Neighborhood in Transition,” or what others might call a gentrifying neighborhood. During my life here (and also preceding it), I have spent considerable amounts of my personal time, money, and social capital attempting to get my neighborhood and city leaders to take seriously the issue of gentrification in Lexington. As a doctoral student at UK, this involved writing a dissertation chapter on artist and hipster led gentrification in 1960s San Francisco. As owner of a northside paper, authoring over a dozen articles on our own city’s promotion of gentrification, and editing another dozen articles written by other local writers. As a teacher of first-year community college students, it’s meant incorporating Lex Gent into class activities. As a northside resident, appearing on local radio shows to discuss northside displacement, and, most recently, producing two youtube episodes totaling 24 minutes to analyze it.

The three-minute allotment of time I am allowed to address your committee will not permit me a full comment, so I will instead focus on one (1) under-appreciated aspect of it: the narrative of Lexington gentrification, and the similarities between it and the narrative employed by deniers of global warming. My professional training in literature and composition makes me sensitive to the importance of naming and storytelling. Simply put, we cannot act on things that we do not name, and once named, our collective tendency is to act upon things we understand to be in need of change.

These are truisms that global warming deniers have long known. With a nod to tactics employed by the tobacco industry, extractive industries in the oil, natural gas, and coal fields for decades underwrote research and bankrolled leaders to deny the existence of human-caused climatic warming. Denial took many forms. It involved dismissing global warming as a hoax; ignoring and disparaging those who took the science seriously; inflating global warming’s few positive potentialities like the promise of a farm-able Arctic Circle; attributing warming to natural cycles unaffected by humanity’s carbon footprint; highlighting minor points of uncertainty amidst broad and near-unanimous expert consensus; and promoting a blind faith in innovation (a government subsidized innovation, at that) to solve it. The denial tactics for global warming are many, but the narrative strategy has remained quite consistent: to forestall collective action so as to keep a profitable status quo, the burning of carbon, chugging along for as long as possible.

Cities are moving away from burning coal, but we do continue to extract value from land in ways that are profitable for a few and damaging to many others. Neil Smith, godfather of gentrification studies, places this value extraction at the center of his definition of gentrification: wealthy groups of investors and individuals purchase property on the cheap in disinvested urban neighborhoods, and then realize returns on their investments through neighborhood transformation that involves replacing businesses, residents, and cultural activities. As with mining coal, this is not as innocuous a process as it sounds, which the creation of this taskforce can attest, and it is one where the few winners rely upon a misinformed public to keep the status quo process of land-rent extraction chugging along for as long as possible.

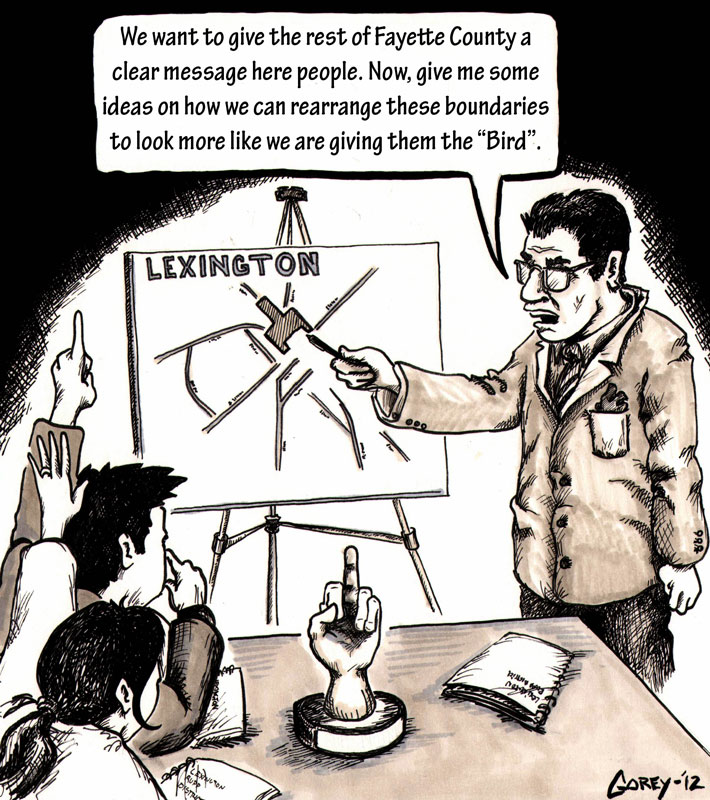

This may explain why, since 2009 when the ‘back to the city’ narrative began to gain steam in Lexington, our local media have instituted a virtual blackout on the word “gentrification,” choosing instead to convey and celebrate this extraction process as “revitalization,” “renewal,” “uplift,” “lean urbanism,” and evidence of a new “can-do” local-first spirit. It explains why I’ve heard city council members describe gentrification as a natural process we can’t realistically do much about; why residents who first mentioned gentrification were often vilified publicly as “anti-community”; why local columnists misleadingly defined gentrification—once they were forced to acknowledge it—as “a politically charged word sometimes used to try to shame people interested in historic preservation, or who want to improve property in which they wish to live or invest”; why the first informal city inquiry into gentrification —held at West Sixth Brewery and featuring two of my council members giving a bro-five to brewery owner Ben Self—was allowed to fizzle out quietly in 2014, after every participant but one denied the existence of gentrification here in Lexington.

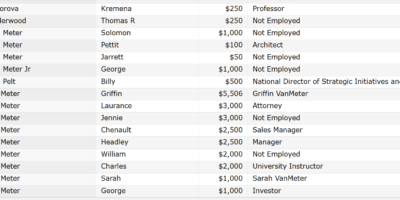

Looking at this esteemed Task Force, I can’t help but notice how many of Lexington’s narrative gatekeepers and beneficiaries of status quo neighborhood transformation are represented: a Vice Mayor who over-plays the upsides of gentrification. The publisher of Lexington largest news outlet, which for a decade now has chosen revitalization over gentrification narratives by a factor of 15 to 1. A housing advocate and Convention Center board member who defended the 1970s destruction of an entire low-income neighborhood, Irish Town, to create a surface parking lot at Rupp Arena because it wasn’t worth saving. Current and former District 1 councilmembers who cozied up to northside land barons are represented, as is the head of a major northside nonprofit that took city affordable housing funds to build homes for artists in an already-gentrifying neighborhood. There is also my property value administrator, who seemed to miss the run-up in housing prices (and who has kept tax assesments low for key gentrifiers), various members of the real estate industry making commissions off the process, and rural preservationists with a history of advocating for horsefarms and highly subsidized Main Street development.

We, the public, are supposed to assume that taskmembers are community leaders who possess both skill and civic virtue. But let’s be honest: a majority of the panel has actively colluded to author this problem—or worked to minimize it as an issue. Whatever you are experts in—and I take it as given that you are experts in something—we can safely say it is not in identifying growing inequality in neighborhoods. Instead, what we have here is the gentrification equivalent of a global warming panel comprised mostly of representatives from the oil, gas, and coal industries. Until this recent history of local gentrification denial is honestly and thoroughly acknowledged, we the public should rightly view your work as more interested in cover, denial, and the ginning up of political support via safe exploration of cosmetic changes that allow the status quo extraction to continue.

As any expert on global warming can tell you, time does matter. Forestalling collective action bakes in consequences with which we and our offspring will have to contend for decades to come. This is also the case with gentrification, where inaction and denial over the past decade have baked in a certain pattern of displacement, runaway property inflation, and cultural upheaval. As this group continues, I hope the curious and committed subset of taskforce members begin to ask how a decade of tax breaks for art hotels, Rupp Arena, underground parking, a Disney-fied courthouse, a new showcase city hall—in short, the entire logic of city development since at least 2010—have contributed to the neighborhood issues city leaders are only now getting around to studying.

Danny Mayer, 430 North Martin Luther King Blvd

Leave a Reply