The last weapon against tyranny in prisons

By Beth Connors-Manke

On July 1, a mass hunger strike began in California prisons. The 21-day hunger strike was sparked by the conditions at Pelican Bay State Prison’s security housing unit (SHU), which like the now-defunct Lexington High Security Unit, subjects prisoners to prolonged isolation and psychological torture. Over the course of the strike, thousands of prisoners took part in the resistance movement.

The organizers’ list of demands included the end to select administrative policies such as group punishment and “gang management” in Pelican Bay; the end to long-term solitary confinement; and the end to using food coercively. The strikers also wanted more “constructive programming and privileges for indefinite SHU status inmates.”

Todd Ashker, a hunger strike organizer, asserted the value and necessity of the action, saying, “We believe our only option of ever trying to make some kind of positive change here is through this peaceful hunger strike. And there is a core group of us who are committed to taking this all the way to the death if necessary.”

When the strike ended, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), released a statement that said: “They [the prisoners] stopped the strike on July 20 after they better understood CDCR’s plans, developed since January, to review and change some policies regarding SHU housing and gang management. These changes, to date, include providing cold-weather caps, wall calendars and some educational opportunities for SHU inmates.”

So while prisoners committed themselves to the trial of a hunger strike, the CDCR felt an appropriate response was caps and calendars — not insignificant things in prison, but clearly not real and necessary change to the unjust and inhumane conditions of the security housing unit.

Hard on the body

Whatever one may assume about the Pelican Bay SHU inmates, it’s hard not to marvel (maybe in an uncomfortable way) at their dedication to their cause. Most of us can’t follow a diet, let alone refuse solid food for three weeks. And there’s good reason for that: a hunger strike destroys the body, sometimes very quickly. Depending on the resister’s health before the hunger strike, if the striker drinks water he or she may last several weeks or months; without water, the end comes much sooner. Jean Casella and James Ridgeway of Solidarity Watch remind us that in 1981, “it took the ten Irish Republican hunger strikers (who were drinking water) from 46 to 73 days to die in Britain’s Maze Prison outside Belfast.”

That’s right. Some hunger strikers do resist until death. And while Solidarity Watch reports that Nancy Kincaid, Director of Communications for California Correctional Health Services, has said, “They have the right to choose to die of starvation if they wish,” clearly the CDCR doesn’t really want dead prisoners — or at least dead prisoners who have captured media attention with their political resistance. To avoid this, many of the hunger strikers in the California prisons – and there have been reportedly over 6,000 at times (while the core group was much smaller) – were watched by medical staff.

The New York Times reported that “every inmate has the right to decline both food and medical care, and he can issue a directive to a doctor not to force-feed him even if he later becomes delirious from starvation. If he does not issue a directive, however, doctors must make judgment calls.”

As brutal as Kincaid’s “They have the right to choose to die of starvation if they wish” may sound, at least it signals that the prison system has been forced to respect the strikers’ freedom of self-determination, if only in this one way. Self-starvation may be a horrific decimation of self, but force-feeding is no less gruesome.

A History and the Politics

“They flung me back on the bed, and held me down firmly by shoulders and wrists, hips, knees, and ankles. Then the doctors came stealing in. A man’s hands were trying to force open my mouth. A steel instrument pressed my gums, cutting into the flesh. Then something gradually forced my jaws apart as a screw was turned; the pain was like having the teeth drawn. They were trying to get the tube down my throat, I was struggling madly to stiffen my muscles and close my throat. They got it down, I suppose, though I was unconscious of anything then save a mad revolt of struggling, for they said at last: ‘That’s all!’”

That’s how Sylvia Pankhurst, a British suffragette, describes her force-feeding. In the early twentieth century in Britain and the U.S., activists found that militant action was necessary for women to win the right to vote. Prayer and patience had not been enough. In England, Pankhurst and others resorted to heckling, rock-throwing, and window-breaking in order to gain attention for the women’s suffrage movement. They were arrested.

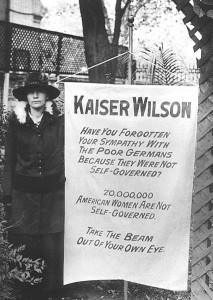

American Alice Paul joined their ranks when she studied social work in England. While imprisoned in Britain, Paul and others went on hunger strike. When the American activist returned to the U.S. in 1910, she brought the radical tactics of the Pankhursts with her. Paul and other suffragettes staged a prolonged protest at the White House, picketing even after the U.S. entered World War I. Their signs asking “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” grew inflammatory, calling President Woodrow Wilson “Kaiser Wilson.”

In response to the picketing, Paul and other suffragettes were arrested and sent to Occuoquan Workhouse, a prison in Virginia where they were subjected to degrading conditions. Paul was placed in solitary confinement and started a hunger strike. She, like Pankhurst, was force-fed. (The film Iron Jawed Angels about Paul gives a visceral depiction of the practice.)

The British and American suffragettes may not have been the first to refuse food in order to protest injustice, but their acts were foundational in the twentieth century, as other political prisoners took up the method. After the Easter Rising of 1916, hunger strikes became part of the national cause for Ireland. Mahatma Gandhi carried on hunger strikes against the British raj. César Chávez carried on strikes outside of prison as he fought for justice for migrant workers in the U.S. Hunger strikes at Guantánamo seem the only major recourse for prisoners held in limbo there, outside the law.

The major difference between the Pelican Bay SHU hunger strikers and most of the examples listed above is that, I’m guessing, most of the SHU inmates were not, initially, political prisoners. But they are now. And, based on the token response from the CDCR, it’s clear this is a political issue that must be taken up by those outside supermax prisons. The Lexington HSU may have been shut down, but it’s kindred high security units have popped up across the country. We can’t acquiesce to them in California, or in Illinois, or in Florida. Join the fight.

As this story went to press, rumors were circulating that the hunger strike in California had not fully come to an end.

Leave a Reply