Editor’s note: This is part three of an intermittently serialized memoir by Ed McClanahan that takes as its working title “Hatchling of the Chickasaw: A Kentucky waterways story.” Parts one and two can be found here and here.

By Ed McClanahan

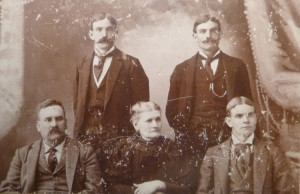

1890s-vintage formal studio photograph of the Johnsville McClanahans, featuring Claude with his identical twin Clifford–two dashing young blades as alike as department store mannequins. Photo courtesy Ed McClanahan collection.

My father’s mother, Stella Yelton McClanahan, lived to be 92, and I came to know her very well, and to love her very much; my father’s father, Claude McClanahan, died before I was two years old. Both the Yeltons and the McClanahans had been landowners and tobacco farmers in Bracken County, near the tiny community of Johnsville, for generations, and both families, I believe, eventually went into local commerce. “In 1884,” according to a local history, “Johnsville had a hotel, a tobacco warehouse, two wagon and blacksmith shops, a dry goods store, a general merchandise store, a doctor, a justice of the peace, and a constable.” My great grandfather Jonce Yelton and his business partner John Jackson (hence “Johnsville”) were proprietors of the general store and post office, and I have reason to suppose (see below) that the McClanahans had gone into the dry goods line, just down (or up, or across) the road from the two “Johns’” General Merchandise & US Post Office.

I don’t know much about my grandfather Claude, but I do have an 1890s-vintage formal studio photograph of the Johnsville McClanahans, featuring Claude with his identical twin Clifford—two dashing young blades as alike as department store mannequins, in matching cutaway coats and waistcoats and high, starched collars, handsome fellows with duplicate dark, upturned mustachios and longish sideburns and black hair parted precisely in the middle.

Unhappily, I have no idea which of the two might be Grandfather Claude, nor of what ever became of Great Uncle Clifford—whichever one he is. To my knowledge, Clifford had no progeny, nor do I recall any shirt-tail cousins showing up from that branch of the slim little sapling that represents all I know of my paternal family tree. I assume (metaphor alert) that the Uncle Clifford twig never bore fruit.

In the family photograph, Clifford and Claude (or vice versa) are standing behind three seated figures, a grim-looking elderly couple—my paternal great grandparents, presumably—and a pallid youth of 17 or 18—a nephew? cousin? red-headed step-child?—with a rabbity, evanescent look about him, as though he too, like Uncle Clifford, were already vanishing from recorded history. (Which, apparently, he did, without a trace; to this day, we have no idea who he … was.) The whole gloomy tableau is framed by the studio’s ponderous, funereal drapery. Nobody cracks a smile.

Now, well over a century later, I have it on good authority, handed down to me by some indescribable yet incontrovertible intra-familial telepathy system (we didn’t talk about certain things, we just knew them), that throughout their long married life, Claude insisted on selecting my grandmother Stella’s hats. My father was like that too; shopping for my mother’s clothes—or mine or, best of all, his own—was among his favorite diversions. (Much more on this in due time.) I’ve even got a touch of apparel-mania myself, as evidenced by the knee-length red velvet cape I affected in the 1960s. The point here being that we McClanahans are indisputably of the dry goods denomination, on the strength of which utterly flimsy evidence I submit that my predecessors were almost certainly the proprietors of Johnsville Dry Goods, across (or down, or up) the road from the Gen. Mdse. & USPO.

I know almost nothing at all of my family’s doings between the time of that photograph and 1908, when my father was born on the little farm just outside Johnsville, and very little of them thereafter until I myself came along in 1932, but it seems safe to assume that things hadn’t gone all that well for the McClanaclan. As far as I can determine, the dry goods store was long gone—I’m guessing it failed in the early 1900s, during the Black Patch troubles of those years, when the tobacco market tanked—, and of the five people in the photograph, by the 1920s only Claude was still sensible to the pinch, and he apparently hadn’t prospered. He was the father of three—my aunt Mabel, my uncle Don, and the youngest, Eddie, my dad—, and he was further burdened with “Unk,” Stella’s older brother (another Clifford, inconveniently, so let’s just stick with “Unk”), who had distinguished himself within the family by never really doing anything at all, and was a heavy feeder as well. The farm, which boasted (according to my late father’s boyhood memories) the requisite good milk cow, a few beef cattle, a couple of hogs, and a garden, could have sustained the whole outfit, even when it wasn’t producing much at all in the way of revenue … but that wouldn’t have supported Claude’s tastes in stylish haberdashery, fine millinery for my grandma (a shy, retiring soul who would probably have worn a flowerpot on her head if her handsome husband had told her to), and, I daresay (knowing my father’s predilections, and my own), a daily infusion of good whiskey if he could get it. And how in the world did he finance a year at the University of Kentucky for each of his two sons?

Well, see, he had himself a little something going on the side: he was what they called a “pinhooker”—that is to say, he was a small-time, short-term speculator in the price of leaf tobacco on its way to market, buying leaf in the street from cash-strapped growers and then immediately reselling it inside the sales warehouse. “These pinhookers”—sniffed a 1960 history of the tobacco industry called Tobacco & Americans, by Robert K. Heimann, an industry flack cum executive—“were not above scouting the leaf country and frightening farmers into distress-selling with rumors of overproduction, disappearance of important buyers from local leaf centers, and the like.” Pinhooking was a nuisance to the buyers, a sometimes-necessary evil to the sellers—and a pretty shady proposition either way you slice it. It wasn’t criminal, exactly, but (people said) it was the next thing to it.

So my family never bragged much about Grampa Claude the Pinhooker, but I like to picture him stationed outside the warehouse door, a stylish anomaly among the milling throng of tobacco farmers, tradesmen, and teamsters, spiffy in his starched collar and upturned mustachios, a boutonniere of sales contracts in his breast pocket, doing a little bidness on the side. Minus the moustache, he could be my dad.

Claude’s career in pinhookery came a-cropper with the Great Depression, when everything else did likewise. His last known employment was in 1933, when my grandfather Poage, my mother’s father, hired him to paint an outbuilding on his farm in Brooksville, the county seat. Both grandfathers died in 1934.

As anyone who has read my work knows to the point of distraction, my favorite characters, real and imagined, are rogues of a certain stripe—charlatans, roughnecks, pranksters, grifters, show people—and I’m proud to add pinhooker to the bills of indictment, and my grandfather Claude to the roster of perpetrators and usual suspects. My hope is that Claude, rest his soul, is enjoying and appreciating the society of Monk McHorning and Philander Cosmo Rexroat and Ken Kesey and Little Enis the World’s Greatest Left-Handed Upside-Down Guitar Player, and that they consider him an amiable and worthy addition to their ranks.

Just mention my name, grampa, and tell ’em you’re with the band.

Leave a Reply