A moveable beast

By Northrupp Center

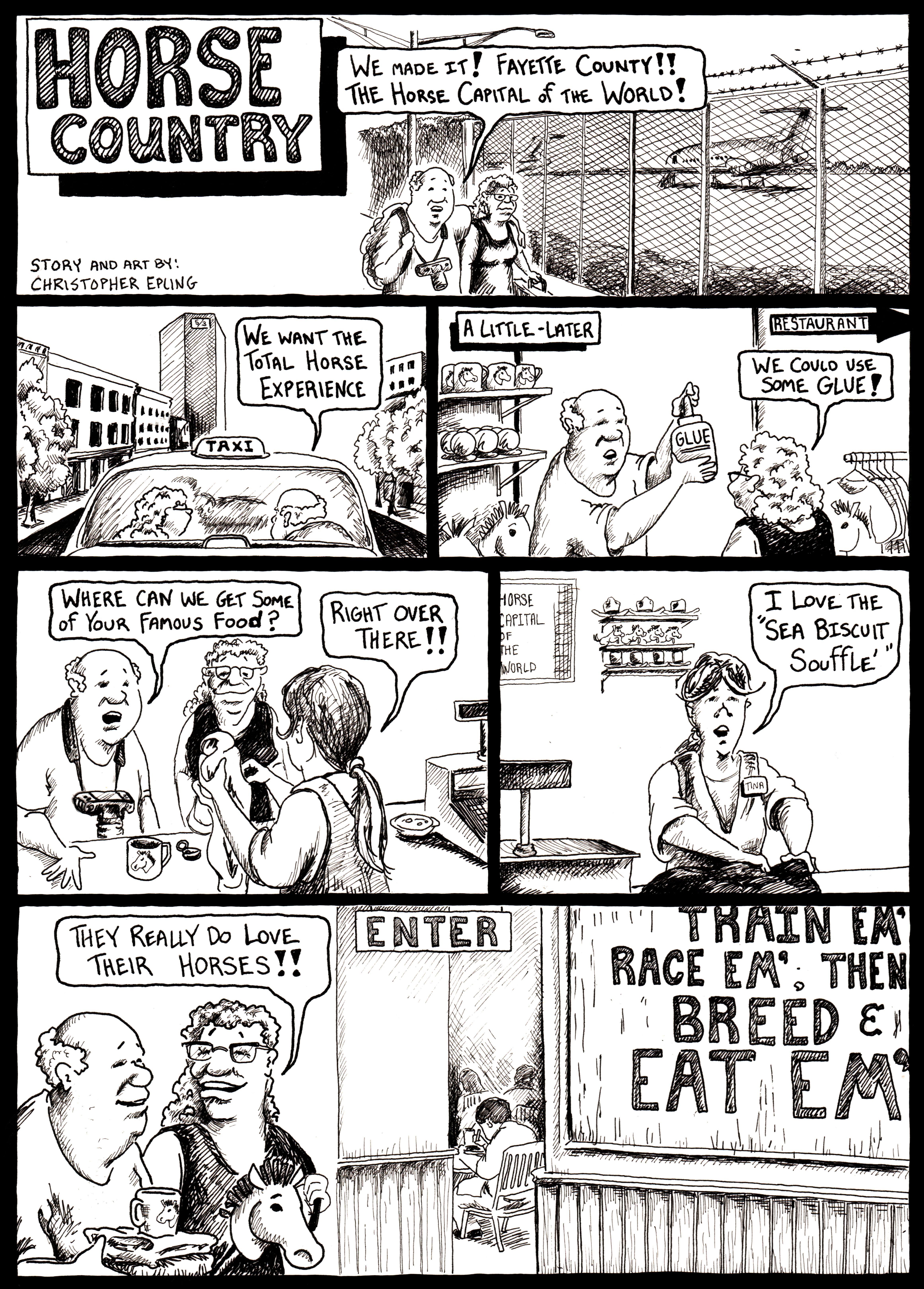

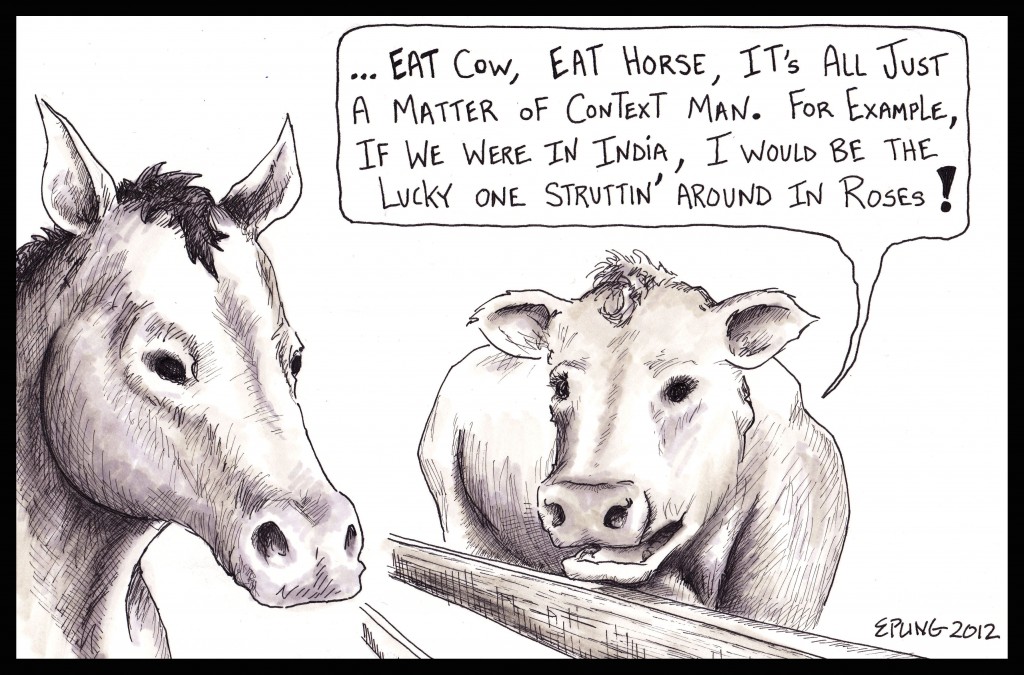

Illustrations by Christopher Epling

Editor’s note: The author claims this article as part two of his contractually obligated three-part look at the 2010 World Equestrian Games. Our lawyers and spiritual advisors have advised us to agree with him; accordingly, we advise you to take heed of a note paper-clipped to the report submitted by our on-staff Fact-Bureau: “Northrupp’s account swings chaotically between being very factual but little accurate, and very accurate but little factual. After four reads, we still can’t say what is what.”

“WEG 2010, a trailer in the wilds of Jessamine County. It was just the whole package, man.”

Gortimer pauses, inhales a spoonful of muted crimson broth chunked with plant and animal remains. “A sashimi appetizer followed by a butternut hoof soup. For the main course, a sea briscuit sitting on a bed of fluffy Weisenburger white grits, the whole thing glistening in a colt marrow demi-glaze. It even showed in the dessert, two scoops of salted spleen ice-cream could rival any Lundy concoction.”

Next to him a pile of greens bleed a mint vinaigrette, sit mounded and weighed upon by shaved pecorino and tendon strips. “The place has since become one of the more upscale of the many Jessamine County knackerias. Trailer 430. Now they understand how to treat the whole horse, just absolute equine artists. The WEG was sort of their, you know, grand opening, or at least as much of a grand opening an underground black market eatery trading in horse flesh is able to have.”

It is late February, 2012, unseasonably warm for the bluegrass, good early mustard weather I will be reminded several times throughout our talks at his formica table. Forty minutes into my trip here, on assignment to cover the Creatives for Common Sense campaign to elect the county’s first ever public knacker, and I am already lost, my sole orientation an undersized window framing a barren wintry view of a pale green Kentucky River. In front of it sits Gortimer T. Spotts, bluegrass native and modern day tinker, patiently answering my questions.

“Just exquisite timing. All those hungry new equine consumers in town for two weeks—and I don’t have to tell you how much the rich love horses. I mean, the Euros and the Japanese were naturally already cultured, but the new blood, the Sheikhs and the corn-fed American set, they really began to get a taste for it. I don’t think anyone disputes that we were the horse-flesh eating capital of the world that fall. It was just…”

My bastard friend from Garrard County pauses momentarily. His eyes rise to the drop-down ceiling. His body relaxes. His spoon falls toward the soup, rests momentarily on a thick brothy bubble and, its glinty weight soon winning, submerges slowly into the thick gruel. Between us, the formica dulls the warming noonday light poking in from outside.

“Fucking beautiful.”

Slaughtering Ferdinand

Ferdinand, sire of Nijinski (1967), grandsire to Northern Dancer (Nearctic, 1961), was produced in 1983 by Howard (breeder) and Elizabeth (owner) Keck for renowned Irish trainer Charlie Whittingham.

The six foot thoroughbred stallion was carved from valuable international stock. With 147 winners from 645 foals, Canadian grandfather Northern Dancer is widely regarded as last century’s most profitable stud. Dead since 1990, the Canadian’s influence nevertheless bled into equine history as late as the 2008 and 2009 Kentucky Derbies, whose inbred winning horses Big Brown and Mine that Bird claimed kinship on both sides. Father Nijinski, voted “Horse of the Millennium” by one British tabloid, won the 1970 English Triple Crown. Not to be outdone by his sire, Nijinski fathered 155 graded stakes winners, one son, Seattle Dancer, selling in 1985 for $13.1 million—$27.5 million in today’s economy.

On the track, Ferdinand lived up to his pedigree. As a three-year-old, the male chestnut won the 1986 Kentucky Derby, toting Bill Shoemaker around for the popular jockey’s final Derby win. A year later the Nijinski sire garnered Horse of the Year honors after a photo-finish victory over Alysheba (Alydar, 1984) to win the ‘87 Breeder’s Cup. Though the following racing season brought disappointment, a losing series of rematches against Alysheba, Ferdinand left the track in 1988 as the fifth-leading money earner of all time, earning over $3.7 million in under five years of racing life.

Off the track and into stud, however, Ferdinand was not so money. In 1988 he arrived for work at Claiborne Farm, a 78-year old horse plantation located outside Paris, Kentucky, whose products, virile winning blood lines, were beginning to dominate the thoroughbred equine stock market.

Ferdi initially fetched $30,000 for each live foal he could deliver. However, results from his “first few crops of runners,” one retrospective would later observe, were disappointing. Stud fees fell, dames came calling less. The stallion was leaking value fast.

Five years after his arrival, 1994, Ferdinand was sold across the ocean to JS Company, which placed the 11-year old at the Japanese breeding farm Arrow Stud. The transaction was mutually beneficial. In Kentucky, the Derby winner’s profitability was sunk. In Japan where American and European equine stocks were riding a bubble, Ferdinand, son of Nijinski, grandson to Northern Dancer, was no penny-stock. His first year in, the stud took 77 mares.

But image and blood only go so far. The champion runner was no breeder, in Hokkaido same as in Paris. By 2000, his last breeding for Arrow Stud, just 10 women called. The next year, early 2001, Ferdinand was sold for salvage value to an operation that most likely—nobody can be sure, this Kentucky Derby horse like all the other steeds—had him slaughtered for pet food sometime before Christmastime, 2002.

Not until the following summer, after an inquiry by Ferdinand’s breeder owners the Kecks, did a journalist for Blood-Horse discover that the Derby-winning grand-sire of Northern Dancer, this poor stud, was no more.

L-FUCK GBTSQ (OMFG)

To the unhip, a Creatives for Common Sense (CfCS) meeting can seem quite disorienting and not a little bit offensive. College-somethings of all ages stand in clusters of three to five and buzz between several tables nearby the stage and the short corner of Al’s Bar, their anarchic migrations, singly and in pairs but never in threes, loosely patterned by the rolling tempo of poured draft beer.

And then there is the name calling. Mostly in passing, often exuberant, and always with a smile. Goat fuck. High fucker. North fuck. Cocks fucker, swap fucker, mother fucker. For someone not attuned, the effect is not unlike walking half-baked into a local chapter of ADD-afflicted Tourette syndrome activists out for a celebratory night on the town. I myself have been called—repeatedly, and by people I believed myself to hold good acquaintance with—a “non-fucker” and “non-fuck.”

Luckily I arrive to this Tuesday night CfCS meeting already hip to the situation. Since this is one of the few moments wherein the written page is certifiably more informative than actual scene immersion, let me lay things down in bare text:

The names are part of a CfCS project to re-brand the city of Lexington as a whole county. Fuckers are not really fuckers. In reality, fuckers are FUCers, or Fayette Urban County-goers. Hence, I am not a non-fuck, but a person not from here. That cocks fucker presumably lives on Cox. SWAP FUCers simply like to paddle. She is not a mother fucker, but a mom of Fayette Urban County.

Safely in and past the first gauntlet of salutations, I order a corn dog and a couple happy hour High Lifes, then draw my attention to the stage, where NoC editor Danny Mayer (PhD, Am Studies) stands, clipboard in hand.

“Clucker FUCers? Any Clucker FUCers here? No? OK. FUCs for FUC’s sake? Anyone here from there? No? Non-FUCs?” Pause. “Yeah, where you from? A Paris FUC? That’s fine, you were once a FUCer back in 1782. I’m Danny, by the way, a proud CROCK FUCer.”

Tonight’s meeting is devoted to the question of expanding or eliminating the official CfCS endorsement for a Fayette Urban County Knacker. In March, the group released a position paper that urged county leaders to take over management of the slaughter of the region’s horses. The knacker, the group contends, will help ameliorate the problem of abandoned, sick, and/or dying horses, while at the same time energize the area’s burgeoning local craft meat industry. The group even has branding ideas, a complete FUCK line of burgers, brats, backstraps, glue, canned hoofer broth and the like.

As I find out tonight, despite the public position paper, the knacker idea has always been a tenuous CfCS proposition. While the carnivores, omnivores, and capitalists were nearly unanimous in their favor of craft horse butchery, other CfCSers felt Mayer bullied the proposal through. Weird fractures were ensuing. Of the relevant swing groups, vegetarians and pescetarians generally stood in solidarity with the knacker position, though not in agreement with the idea the position embodied. Meanwhile, vegans, deep agriculturists and several old-school Lexingtonians wavered between passive an d passionate opposition.

d passionate opposition.

The three positions, tonight at least, go something like this:

For: Horse is good, lean meat that has untapped artisanal potential. Regional food is what’s in right now. Since the Bluegrass is already branded “horse,” it’s a market waiting to be taken. Japanese and Mexican migrants represent, respectively, this county’s most important creative and cheap labor demographics—and they also represent the two largest consumers of horse meat per capita. Fetlock burgers would be a wonderful local addition to Al’s menu.

Vegetarian position: Personally against eating horse flesh, but society and laws allow other meat eating to continue. Good oversight and emphasis on craft butchery might help ensure humane treatment of horse. Public revulsion to horse meat consumption might spread to cow, chicken, goat, buffalo, alligator, quails and other fleshy beings. If CfCS is OK as an organization housing Clucker FUCers and Goat FUCers, there should be room at the table for FUCK FUCers.

Against: Eating meat is barbaric and destroying the planet. Saying FUCK is vulgar. We love Lexington.

The debate was pitched. I observed four near-miss fights owing to the real or perceived mis-labeling of FUCers as FUCKers, the closest occurring when Francis (PhD, UMass),a vegetarian CROCK FUCer, felt that some Creatives near the bar were labeling him a smelly CROCK FUCKer, a slight mountain twang and the subtle breath of difference between a hard and soft “c” making all the difference this steamy night between a smiling leaf-eater and a foul devourer of equine flesh. No fewer than eight CfCSers crossed their arms and threatened to leave the movement.

But after two hours and 17 craft pitchers, Aaron (PhD, UK) successfully brokered a deal, which brought together a broad coalition ranging from meaty CLUCKer FUCKers on down the food chain to leafy GleanFUCs.

In place of the narrowly conceived job title of knacker, Aaron’s plan emphasizes the inherent diversity of the knacker idea. The new position, rebranded L-FUCK GBTSQ (OMFG), keeps the focus on the Lexington-Fayette Urban County knacker, but expands the agricultural reach to include grocers, brewers, tanners, steers, quails and any other manufactured farm goods that might spring forth from Fayette soils.

At this point, Al’s is past bonkers. Near the stage, a group led by Mayer has begun chanting, “FUCK, the whole horse and nothing but the horse!” At the bar a vocal splinter group returns fire, shouting, “L-FUCK GBTSQ (OMFG)! We do it all!” In between, creatives dart to and fro, singly and in pairs.

Here is where we’ll stay

Crisis averted and solidarity restored this night, Mayer concludes the meeting with a variation on a speech I’ve heard several times. Tonight, ten minutes after starting, he ends it like this:

“It’s about time we city-dwellers joined the rest of the state. We are city, sure, but like the rest of the Commonwealth we are also county. No better, no worse. We are Fayette Urban County.”

It’s hard not to feel Mayer’s intense passion for ol’ Fayette. His final statement, delivered in iambic staccato bursts, WE-ARE Fayette URBAN County, manages to fill both wings of the bar and whip the remaining FUCers into a frenzy.

As I pay my tab, Wes (PhD, IUP), sensing a moment, tempts the mob with a spontaneous rendition of the old folk standard “Fayette County.” My debt settled, I head out the door, a chorus of drunken off-key voices following me onto Limestone like a fire siren receding into the night. “Well, we were come to Fayette County, and here is where we’ll stay……”

To be continued.

Northrupp Center holds the Hunter S. Thompson/Charles Kuralt endowed chair of journalism at the Open University of Rio de Janeiro (OURdJ). He splits his time between there and Lexington, KY.

Leave a Reply