Backyard garden constructed at author's old home in year 3 of visiting the Lexington Farmer's Market.

Park markets and city hall

By Danny Mayer

I started visiting the Lexington’s Farmer Market (LFM), sporadically, in the second summer after I moved here, 2001. A year later, after returning from a honeymoon in Italy, my wife and I began regularly patronizing the downtown Saturday market, then held on Vine Street.

A graduate student employed by UK at 12 thousand dollars a year (a salary that has changed little in over 10 years despite many graduate students teaching a heavier load than tenured faculty), in 2002 my limited money needed to stretch as far as possible. On market days, I’d bring $20, cash. Julie and I would make our way east down Vine Street toward Phoenix Park, making a list of needs, wants, weights and numbers, before making purchases on our return westward shuffle toward the Central Bank building. That first year we mostly bought tomatoes, beans and cucumbers, maybe a flower for Julie, and some green peppers and herbs if we could stretch our money.

At the first market back from our honeymoon, in mid-June, I purchased a small basil plant that had been marked down to a buck—the last of my weekly money. The person working the stand must have felt sorry for my late-season interest in basil growing because he threw in, free of charge, an extra basil plant. (He also could have been simply trying to get rid of plants that, in June, he figured no other saps would buy.)

I grew basil that year, 2002, and by damn, by September I was able to move a portion of the $20 we devoted to basil purchases into other products. (For newly-weds recently returned from Italy, basil represented a substantial chunk of our LFM budget.) Sometimes we tried squash. Other days we splurged on hot garlic mustard, bread, cinnamon rolls or okra.

The next year, I bought my basil plants earlier, and shitloads more of them, and added a couple tomato plants into the mix. As our tomato and basil costs began to get covered by our home agricultural production, we devoted our $20 to other LFM products that, previously, we had purchased at cheaper big box stores like Kroger: lettuce, corn, apples, garlic. In a sense we made money because growing some of our food meant we needed to buy less of it, but practically speaking, our backyard gardening meant that shopping at the LFM became more affordable. Our money was freed to purchase a wider variety of goods.

As I have continued to grow more of our own veg—beans, squash, lettuces, carrots, potatoes, okra, beets, herbs—our allotment of farmer’s market money has also grown. We now spend close to $10 on supplementary seasonals—early or late lettuce, fall apples, summer garlic and corn—and still have between $5 and $10 from our original $20 allotment to put toward eggs, meat, cheese. While the bratwursts, bacon, pork or whole chickens we buy are pricier at the LFM, the discount we receive from growing our own food has made these locally sourced products more affordable. In fact, since 2004 our food costs have remained mostly flat, even as we have slowly transitioned toward shopping exclusively at the more pricey farmer’s market, and even as food costs globally have increased. If anything, when it comes to food we now spend less.

Farmer’s Markets and home production

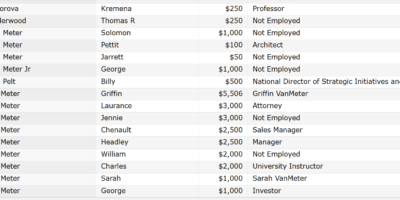

About a month ago, I cited a Fall 2010 survey conducted by a UK rural sociology class led by teacher Keiko Tanaka. The class spent two weeks visiting the three Lexington Farmer’s Market locations (Fifth Third Pavillon, Rupp, and Southland), where they surveyed over 500 market patrons on a variety of food and market-related topics.

My article used the most publicized findings from the survey—that market patrons were disproportionately rich and well-educated—to call for expanding the geographic reach of city farmer’s markets as a means to expand its economic demographics. My basic premise: the city should actively support and encourage the creation of 5 weekly markets on public city park land as an important, cheap, step in granting more city residents access to an increasingly important city resource: our farmer’s markets.

Though I didn’t report it then, the student survey also unearthed two other interesting statistics: (1) that a large number of Lexington Farmer’s Market patrons grow (60%) and preserve (50%) their own food, and (2) that patrons rank “afford-ability” fairly low on their list of food concerns.

One way to understand these two figures is to attribute them to the most common critique of the local food movement: that locavores and other foodies are overwhelmingly wealthy and educated. This upscale demographic, the argument goes, has both the spare time needed to grow their own vegetables and the money to have little general concern for food prices.

There is little doubt that this argument applies here in Lexington (as most elsewhere), but I think the LFM survey also offers other ways to understand how the Lexington Farmer’s Market, like all markets, works to stimulate smaller agricultural and economic acts of production—what Wendell Berry has called an economics of subsistence.

Though I was not interviewed for the survey, I do fall into the over-educated, above-median family income, white, living near downtown demographic that the LFM study found comprises the largest portion of LFM patrons. A 10 year consumer at the market, a grower for eight years and a preserver (freezing) for about five or so years, my own market story also seems applicable to the general trajectory of farmer’s market participation.

The UK sociology survey indicates that the LFM has a regular, long-term customer base. Even though the class conducted their study during the World Equestrian Games (when, theoretically, according to city leaders and leading economists the town was flooded by tourists), 85% of respondents reported being repeat visitors. Nearly half surveyed hit the Lexington Farmer’s Market once or more weekly. Over forty percent had shopped at the LFM for more than six (6) years. A full quarter had been visiting for over 10 years. These were dedicated shoppers.

Long term patronage of the LFM, it seems, also does something to us as consumers: it turns us into partial producers of our own food. The majority of respondents who claimed some form of home food production (vegetables, poultry, herbs) had been gardening for over five (5) years. The majority of folks claiming to process their food had been at it for over ten (10) years. While the questions did not specifically address the connection between long-term LFM participation and food production and processing, there seems to be some correlation, or at least a fairly demarcated trajectory. Regular consumption of market goods tends to lead one, first, to grow food at home, and eventually to processing excess veg for home consumption.

City council thoughts

We tend to think of markets in terms of consumption—of what markets offer us consumers to purchase. But they do more than that. The Lexington Farmer’s market, like most farmer’s markets, doesn’t just satisfy community demand to consume locally sourced food. It also stimulates market patrons into producing their own goods—tomatoes and beans, cilantro and basil, chicken eggs and pears. Farmer’s markets, then, aren’t just places of consumption where we wealthier folks get to spend our money with a clean conscience, they’re also locations that instill beneficial economic impulses of micro-production.

City council would be wise to understand food markets not simply as lifestyle choices, but rather as an economic ballast or substrata that fortifies household units. Apparently, the open format of farmer’s markets stimulates latent consumer demand to become backyard producers and subsistence farmers.

How they do this, I can’t say for sure. I’d imagine that, as customers passing through all those Farmer Market stands, we’re bombarded with direct visual advertisements for colorful, fresh food. Sensory overload. Like other types of advertising, this doubtless has an effect on us, makes us desire veg. Or maybe market-growers are like me: they see all that food and think, shit, I can do some of this myself.

The sort of economic transactions that circulate around growing one’s own food may not produce the eye-popping (theoretical) statistics one might find in, say, a Rupp Arena re-do or a WEG economic report, nor will such transactions pre-dispose certain wealthier members of the public to benefit greater from city projects than everyone else (as downtown development has and does), but that doesn’t mean that such transactions are, in aggregate, small or not needed.

Thus far, in their race for new creative solutions to rebuild the city via expensive horse, basketball or bourbon economics, city leaders have neglected more simple, less costly, old world solutions like supporting the expansion of public city markets. Currently, most Lexingtonians must travel to the city core to get access to the city’s farmer’s markets. Like most things here, this has meant that the residual economic benefits produced through regularly patronizing the LFM has primarily been offered to those living nearby downtown or having access to a car (and the free time) to travel on Saturday, Sunday, Tuesday or Thursday afternoons. In locating in such narrow times and locations, our farmer’s markets have mostly bypassed our suburban neighborhoods, the very places where residents tend to have home lots conducive to backyard gardening on an economically beneficial scale.

Of course, things don’t have to be this way. We (by which I mean you) should demand your city council to facilitate the development of smaller market access throughout the city.

Jackson

Excellent read. I’m so intimidated by the idea of being a first-time gardener but feel such a deep urgency to get going. This reading instills further confidence.

Being a poor college student, I can’t wait to have extra cash for the market

Danny

If you’re worried, start small. You’d be surprised how much a couple tomato plants produce. (Those giant tomato varieties produce less, the grape kind produce tons.) The last 2 years I’ve had an easy time with okra, too. Pretty abundant. Cilantro, not so much for me. Peppers have been kind the last 2 years for me, though most unkind for the 3 or so years previous. Potatoes have been a more recent fun crop. (You can get potatoes at Fayette Seed, off Red Mile Road.)

Some things will work, some won’t.

Happy gardening.