NoC News

The Community Action Council, God’s Pantry, and the Urban League of Lexington-Fayette County have sponsored two forums to help citizens, especially northsiders, learn about Urban County Council candidates.

District 1 forum

The September 30 candidate forum brought residents out to Douglass Park on a balmy and breezy night. District 1 hopefuls Marty Clifford and Chris Ford addressed a modest but interested audience. Candidates answered questions from moderator Beverly Henderson and audience members.

The first question asked each candidate which specific issue he would like to be known for as a councilmember. Clifford affirmed his commitment to being a “full-time” councilmember, allowing him to represent the First District’s needs in the many meetings held by Council. Ford began his answer with affordable housing, also stressing economic empowerment and the relocation of Bluegrass Community and Technical College (BCTC) to Eastern State Hospital, located near West Fourth Street and Newtown Pike.

These issues – housing, poverty as it relates to education and job skills training, and the First District’s voice on Council – were the themes of the night.

Audience members asked pointed questions about the Affordable Housing Trust Fund (AHTF). An issue that has been under debate for several years and is strongly supported by several community groups, the AHTF would contract with non-profit organizations, for-profit entities, and local government to build and maintain affordable housing. “Affordable housing” is defined as housing that requires families and individuals to pay no more than 30 percent of their income for housing.

One resident, who had just received his property tax bill, complained about the potential for another tax (the proposed method for establishing the fund) when he is already financially strapped. Both candidates sympathized with the questioner, but emphasized that for the average household the cost would be relatively small. Clifford and Ford agreed that the result, more decent and safe housing for Lexington residents, would benefit all.

Another questioner pushed the candidates to clearly articulate their support for funding the AHTF. This audience member asked the candidates if they would commit to making sure that every dollar that goes to PDR (the purchase of development rights for farm land around Lexington) is matched by funds going to housing in the inner city.

Clifford had admitted earlier that he was not very familiar with the work that has been done on the AHTF so far, but that he would support it because it was a “make sense deal.” He suggested that funding for the AHTF might be gathered more incrementally than has been previously proposed.

Ford, a member of the original AHTF commission and currently the president and CEO of Reach, an affordable housing organization, detailed the AHTF model for the audience. He strongly and clearly promised to push the AHTF while on Council.

Earlier in the conversation, Clifford, who has spent most of his career in real estate finance and specializes in low-income housing, had pointed out another housing issue on the horizon for District 1: the gentrification that may come with the BCTC move to Eastern State Hospital. To guard against that, Clifford said an effort should be made to help residents near Eastern State buy their houses now, before real estate prices go up with BCTC’s arrival.

Candidates addressed poverty in District 1 by stressing the need for accessible and affordable education and job skills training. Ford cited the need for a program similar to the now-defunct Mayor’s Training Center which provided job skills training. Clifford suggested models like one from San Jose in which community college education is free because of private investment.

The most evident difference between the candidates that night was their positions on dealing with government’s perpetual “lack of funds.” Ford argued that his experience in government and grant writing would help him find money for vital projects. He pledged to go Frankfort, or even Washington D.C., for funds if necessary. Clifford’s approach, which he said is based on his past grassroots successes on the north side, relies on citizen volunteers to get projects done, creating stronger community in the process.

At-large forum

Nearly a week later at the downtown public library, the six at-large city council candidates also convened for a public forum moderated by Nancy Jo Kemper. Attended by nearly fifteen residents, it also focused on issues important to low-income residents of Fayette County. After an introductory statement, the candidates fielded questions focusing generally on affordable housing, utility rate increases, and generating revenue to better fund community engagement with Lexington’s underclass.

When asked, “How can city government get the community to engage with the city’s low-income residents?” candidates offered a variety of specific and broad-based ideas. George Brown began by noting how little knowledge southside Lexingtonians have of northside poverty. “Main Street [is the] Mason Dixon Line of Lexington,” Brown observed. For Brown, educating the city about the faces of poverty throughout the city is an important first step.

Kathy Plomin, who has spent the last decade as president of United Way Bluegrass, cited the need for greater partnerships with social service agencies like the United Way. In particular, she noted her role in the creation of 211, a call line for community resources geared toward the city’s poor and working-poor residents. Such private initiatives, she claimed, could be partnered to more efficiently provide the city with better information regarding what needs Lexington’s low-income communities have—and where in the city such needs arise. Linda Gorton, who along with Chuck Ellinger already sits on the city council, drew on her professional and civic interests in nursing by proposing a health tax to give the health department a regular funding srteam for low-income residents. She also called for a renewed focus on providing services for Lexington’s aging population.

Gorton also hit on a theme picked up by several candidates: the need for more education as a path to economic security. In noting that no “simple answer” would solve Lexington’s poverty, Steve Kay described a need to bolster K-12 education. Kay cited the recently built William Wells Brown facility as a model for integrating school and community resources into one neighborhood-focused center.

Brown, who also noted the need for better education as a way to combat systemic poverty, focused instead on preparing economically poor students for university life (and finding ways to better grant them access to college), particularly in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). Gorton stressed a different sort of educational training, focused less on university training and more on the development of job training programs that do not require university degrees. For Gorton, the key word is “skills” production rather than educational degree production.

As with the District 1 candidate forum, the question of the city’s affordable housing trust fund (AHTF) came up, though it played a significantly smaller role in the at-large debate. Every single candidate supported the need for a trust fund, though few candidates categorically supported it. Chuck Ellinger, who sits on the city’s affordable housing task force, supports the idea of affordable housing, but claimed at the forum that now was not the right time to raise the fees needed to fund it. (Ellinger also claimed that the city has balked at funding the $24,500 affordable housing impact study, needed as a baseline for moving forward with more specific needs and funding assesments.)

Gorton mirrored Ellinger in noting that the “climate is not good for new taxes.” She stated a general desire to find money in the budget and to sit down with the development community (which has under-built affordable housing) in order to try to partner with them. Kay provided the most specific support, though it was mild. He claimed support for “some form of funding” for AHTF, though he noted he was “not prepared to say exactly where it needs to come from.”

The question of funding initiatives for low-income citizens bubbled to the surface at several points during the forum, such that “funding” often supplied the boundary-points for discussion. The catch word used by several candidates was “increasing the pie,” generating more tax revenue for the city to fund initiatives geared toward helping its citizens. Ellinger observed that 70 percent of the city’s operating funds are earmarked for specific city staff; 10 percent goes to servicing city debt. This only leaves 20 percent to disburse in the form of city projects and initiatives, he claimed.

On the question of increasing the pie, the candidates suggested different ideas. Ellinger stressed his pledge to provide “basic services” like police and fire departments and to fiscal conservatism. Brown suggested education in the STEM fields as a way to grow the economy and the tax roles. Plomin focused on attracting more grants and corporate partnerships.

Steve Kay and Don Pratt offered more specific ways to generate and disburse money during a time of shrinking tax bases. Kay first noted that providing services to Lexington citizens is a matter of priorities: “Where there’s a will, there’s money,” Kay claimed. And then he supplied a vision for how he sees the city engaging citizen needs. Pointing to the Lexington Farmer’s Market and the development of the London Ferrell Garden as models, Kay claimed that “government’s role is to provide seed money, guidance, support” to energize people’s desires and needs, a sort of small-scale, bottom-up, public-private partnership.

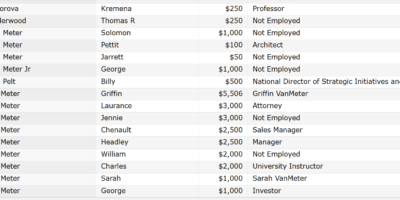

For Pratt, whose candidacy is more geared toward changing the culture and financing of city government, part of the problem lies with how the pie is broken up. Mayoral races, and city council races, Pratt contends, have become too expensive, with Lexington mayoral candidates now spending over $1 million and his fellow council candidates running tabs aver $20,000. Candidates are pre-determined to accede to big business interests that tend to fund such candidacies, and it’s the citizen who loses out in terms of city priorities. Pratt is calling for true publicly funded races that, he argues, would increase citizen participation at all income levels.

Pratt’s plan to grow the city’s economic pie includes two planks: he proposes to save money in the budget by appointing a publicly elected auditor to ensure Lexington’s tax dollars are being spent ethically and transparently; he also hopes to lay the groundwork for generating money (growing the pie) by re-starting hemp production (and taxing it) and building a medical marijuana hub in the city (and taxing it).

Election day is Tuesday, November 2.

Leave a Reply