I spent much of the last two weeks learning about Industrial Revenue Bonds (IRBs) to better understand the city’s proposed deal to issue $40 million of them to the mysterious private development company Astana, LLC, for a boutique hotel in the Distillery District. You can read the first of what should be several reports on that Astana deal here, which first came to City Council for consideration during last month’s May 25 City Council Work Session.

Astana’s IRB has understandably drawn most of the focus from that meeting, including mine. Whatever the ultimate discount that ends up accruing to the company through the city’s help in issuing it a $40 million loan, the public leverage is bound to be significant. In our city at least, the Astana deal is big news, in need of deep coverage.

But two other documents from that May 25 meeting also stood out to me as newsworthy, and neither are likely to get the sort of attention that they deserve. The first was a Council authorization to enter into a 13-month rental agreement with Civic Lex for an office on the 4th floor of the city’s Pam Miller Downtown Arts Center, located across from City Hall on Main Street.

The second was a $120,000 professional services contract with Millennium Learning Concepts, LLC, for a Diversity and Inclusion Workshop for city employees.

At $40 million, the Astana IRB represents our city’s post-covid return to big-project rentier capitalism, in which governments provide extra help and reduce market competition for a few high-wealth actors. It’s a form of civic inbreeding that ensures the right kind of people make the acceptable kind of investments. In this city of slave-owners-turned-horse-breeders, rentier capitalism is as native as the bluegrass we so cherish.

The CivicLex and Millennium Learning Concepts documents, meanwhile, tell a more minor tale of rent-extraction in the post-George Floyd era: how governments provide extra help and reduce market competition for a select few community and activist groups whose expertise lies mainly in getting grants and winning government contracts that (in turn) provide their income. These groups derive their community value not by providing any added useful community products or services or ideas, but rather by holding a monopoly on the delivery of such grant-given community contracts.

With this in mind, the CivicLex and Millennium Learning Concepts contracts, though collectively registering far less on the city accounting scales than the Astana IRB subsidy, are worth a closer look as small-scale examples of community rent-seeking. This piece will focus on CivicLex’s rental contract with the city, and a second will look at Millennium Learning.

The dubious community value of progressive Lexington art

The 13-month CivicLex rental lease for office space at the Pam Miller Downtown Arts Center will allow the city to house the CivicLex “Artist-in-Residence” program. That program, which continues a policy of granting the non-profit CivicLex unique access to the government that stretches back at least to its role facilitating the city’s gentrification dialogue, is funded by a $75,000 National Endowment for the Arts grant awarded to CivicLex and administered by the Bluegrass Community Foundation.

The “Artist-in-Residence” program reaffirms a key rule of MALGA activism: the belief that art and artists (those selected by grant-writing groups like CivicLex) are uniquely positioned to solve thorny civic and social problems.

The CivicLex grant will pay up to 3 local artists a $15,000 stipend to “embed” in the LFUCG departments of Environmental Quality & Public Works, Finance, and Social Services, ostensibly to provide their (artistic?) expertise in dealing with things like bike trail development, the awarding of Tax Increment Financing and Industrial Revenue Bonds, and managing the city’s affordable housing trust fund.

It is debatable what the city will get from the “Artist-in-Residence” program other than a surface aesthetic of community engagement and maybe some pretty art or well-written plays. CivicLex director Richard Young, in a typically bullshit-dripping statement, builds his case for CivicLex artists off the back of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Now, more than ever, it’s clear we need to focus on bringing more residents into the process of governmental decision making – especially communities that have historically been excluded,” the Chevy Chase-raised Young claimed in January of this year. “We’re building this project to increase equity and representation for all Lexingtonians in decision making processes, find creative solutions to problems or areas where City employees feel stuck, improve communication, and celebrate the underappreciated work City employees do.”

When it comes to artists being historically excluded from the process of governmental decision making, Young seems to either have no shame or a severely limited civic memory.

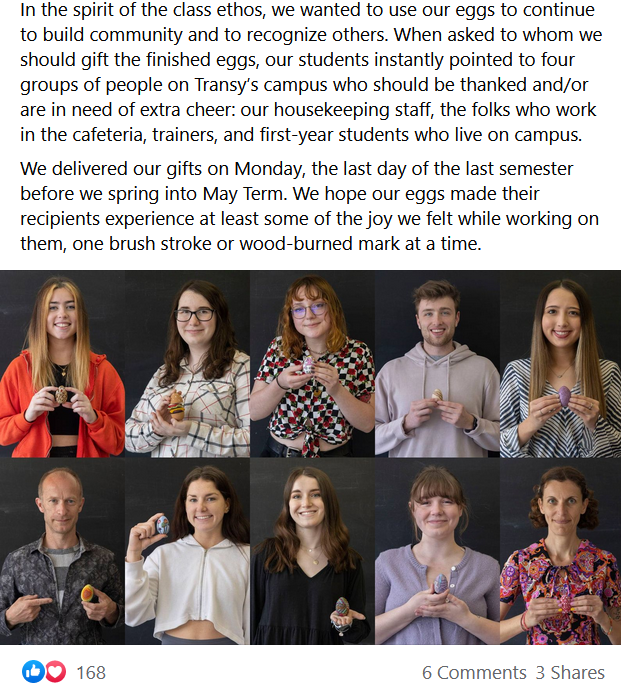

If you will recall, the arts—including many of the artists governing the CivicLex artist board—were held up in a similar community-empowering way during the previous 8-year administration of Jim Gray, an art collector himself and champion of local arts who was so loved by local artists that he received a fancy send-off when he left office. The love-fest was organized by….Lexington artists–and CivicLex “Artist-in-Residence” board members–Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova. (Todorova and Gohde also host an annual “Community Engagement Through the Arts” program that is regularly attended by city council members and other area hotshots.)

CivicLex itself is the re-branded, Jim Gray-era, arts-focused civic organization you used to know as ProgressLex, formerly headed by Kentucky Democrat Party bigwig Ben Self, whose West Sixth Brewery houses the “Bread Box” artist space. Before re-branding as CivicLex, ProgressLex held annual “unconferences,” attended by elected officials, that regularly focused on embedding art into the city.

CivicLex’s current headquarters are part of the Plantory (also formerly housed at Self’s West Sixth), which is another empowered civic organization whose Obama-era approach to thorny discussions like gentrification found artists getting paid for using the arts to evade actual community conversations.

Young, CivicLex’s director and founder, made his name in the city by writing an affordable housing grant that prioritized importing artists into a gentrifying northside community that was rapidly displacing poor non-artists. (Young also spent time as the director for Central Kentucky Youth Orchestra, adopted by the same community as evidence that gentrification was being handled by community leaders. The renamed “NoLi” neighborhood, in fact, gentrified by presenting itself as Lexington’s Obama-era arts-focused neighborhood for social justice activism.)

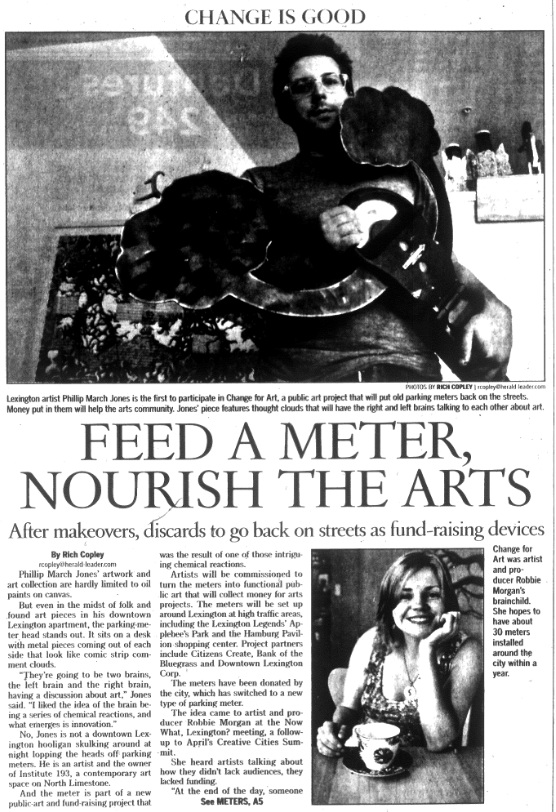

I could go on. There was the 2010 “Creative Cities Summit,” to which our new Mayor sent his entire staff to learn how to integrate art into city practices–part of the larger city push to embed more art into the city in order to attract a “creative class” of outside, moneyed professionals. Here’s a youtube video I did on that decade-long push.

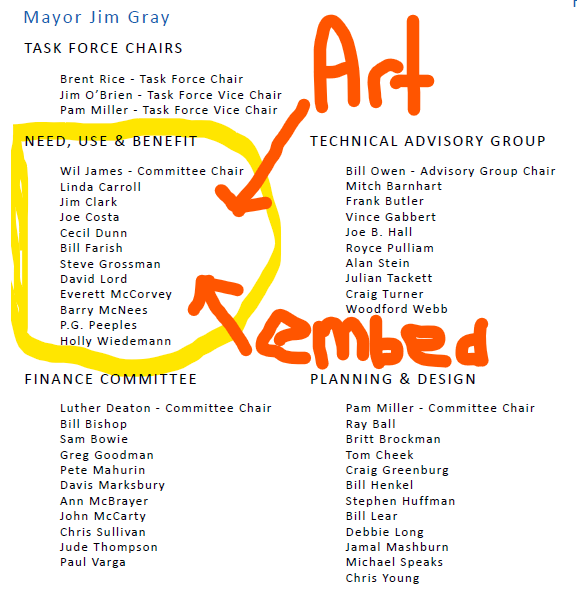

Or how about the 2011 “Rupp Arena Arts and Entertainment Task Force,” which authorized the city’s $300 million investment along Broadway and Main Streets? (I’ve helpfully bolded, italicized, and changed the font color to better emphasize the important descriptor for literacy-challenged art activists.) That 47-person Task Force convened by Mayor Jim Gray was split into four sub-committees, with the “Needs, Use, and Benefit” subcommittee looking specifically at addressing the “needs of the art community.”

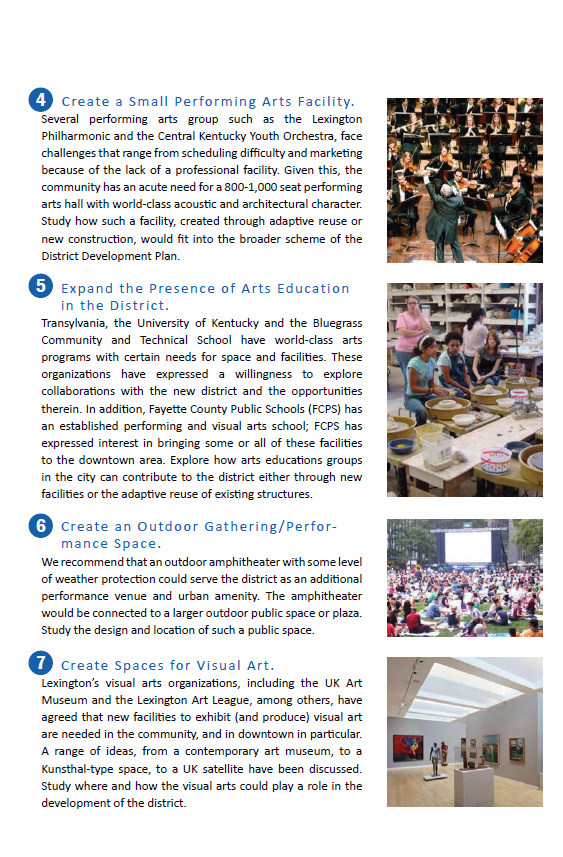

That sub-committee came up with these certainly arts-focused suggestions as a means to sell the city on renovating Rupp Arena for the UK men’s basketball teams.

Here’s the point. As a class of Lexington residents, artists of all colors, genders and sexual orientations were one of the most empowered groups in this university city—up there with real estate developers, chefs, male collegiate basketball players, beer and spirits magnates, UK and Transy professors, and horse-farmers. From graffiti artists and print-makers to community engaged arts classes, the city has done nothing but enthusiastically celebrate and embrace the arts and the people who create them. In what world is CivicLex living that it can define artists as marginalized and in need of greater connection to government representatives?

If one agrees that the problems of broken government exposed by Covid were long-standing—as nearly all national conversations about the past year’s events note—then it is difficult to view, as Young and our city council do, the necessity of giving the empowered artist class of last decade another outsized role in directing city conversations about our future. They already have that power.

And they failed miserably with it. Instead of focusing on “finding creative solutions to problems or places city employees feel ‘stuck,’ trying out new approaches and ideas, and celebrating underappreciated work,” to quote CivicLex’s current rationale for embedding artists, last decade’s artist class focused instead on the solipsistic project of building up and celebrating their own Lexington art community, which they mostly set in places where low-income people used to reside.

And yet, incredibly, CivicLex/ProgressLex artists are set to be given, again!, special city access and a great big bullhorn on the same pretenses as last time: that this class–if managed properly by a well-trained non-profit board of progressives–is uniquely able to speak up for actually civically marginalized Lexingtonians like substitute teachers, plumbers, cashiers, laundry-machine operators, bus-riders, and the like. My goodness!

This is not to suggest that CivicLex’s artists will be quite as solipsistic as their last decade of collective work in this city showed them to be. One would hope that, in 2021, selected artists will demonstrate an awareness of the local world they inhabit. As someone doing that work for over a decade, I welcome them (finally) into the fold, though I don’t hold much hope for civic novices and patron-seeking artists to generate many novel ideas. Even art cannot outrun history.

But let’s be clear: however serious such embedded artists may be, CivicLex is using them to re-assert its own self-generated brand as an important community change agent—despite having, like our local artist class, a history of generally regressive or insubstantial community output. Maintenance of that community brand through un-projects like the Artist-in-Residence program ensure the non-profit “bringing daylight to the issues, policies, and procedures that impact Fayette County, Kentucky,” can continue collecting, Astana-like, even more un-accountable money from wealthy national foundations as a means to insert itself and assets into the local Lexington fabric.

But then again, that’s the point. CivicLex is telling us, and Council is agreeing, that any seriously considered community engagement with the city’s Finance, Social Services or Public Works departments must be rendered through artists strategically chosen by the people and profession who got things so wrong last time around.

Good for CivicLex and their 3 selected artists. But, whew boy, it sure seems a shin-shot to actual art, much less the oh-so-much-more-important area of community change.

In tomorrow’s post, I will look more closely at CivicLex’s rental agreement.

Leave a Reply