Working rivers and locked communities

In part one, Wes recounted the state and federal policy to place the Kentucky River lock and dam system into permanent “caretaker status,” a process that involved welding the locks shut, downsizing lockmaster employment, and discontinuing upkeep.

By Wesley Houp

Like his father, Chuck Dees’ early years with the Corps were spent on relief duty. From ’51 to ’55 he traveled the river with a repair party delivering necessary supplies, materials, and manpower to ensure the locks were in good working order. In the summer of ’56, Dees came to lock 7 at High Bridge and stayed for the next 22 years.

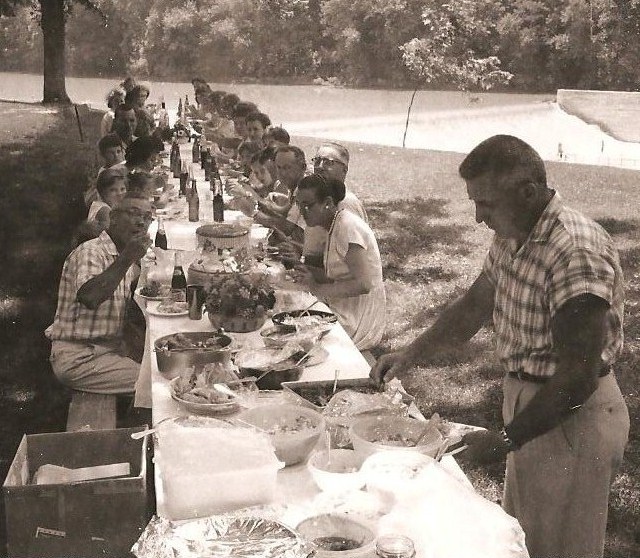

While the properties surrounding the lock and dams were referred to as “Government Reservations,” or “Government Project Lands,” the houses and grounds at lock 7, and the rest of the locks for that matter, were anything but the barren and sorrowful places these names tend to evoke in popular consciousness. The properties were lush, large shade trees provided relief from the summer sun, the spacious grounds were fertile for family gardens, and the ever-present river provided all sorts of opportunity for recreation, leisure, and the simple but essential contemplation of the current of life.

The two houses at lock 7 were of sturdy construction, much like typical two-story, white, wooden-framed farm houses of the early 20th century. “It was a beautiful place to live and raise your family and work,” recalls Dees. When the lockmaster wasn’t locking boats, he occupied himself with maintenance of the grounds. And the grounds were pristine, the lawns uniformly mown, the houses white-washed and clean. The respect lockmen had for position and property is reflected in the general respect paid by those who benefited the most—the public.

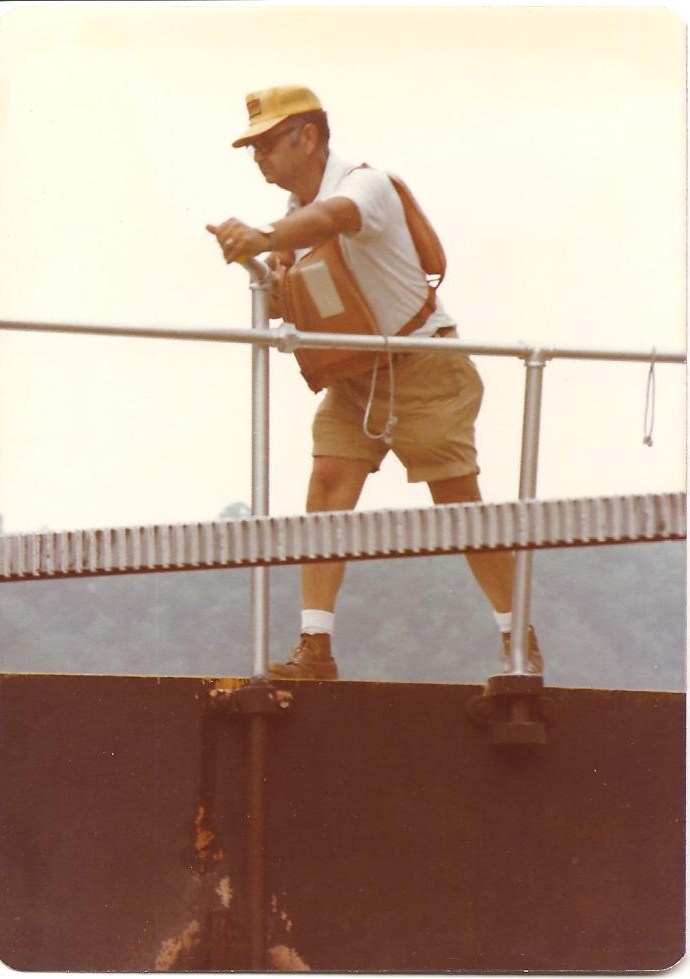

Lockmen wore clothing befitting their office, too. Always a hat. A pressed shirt. Clean, pressed workpants. Maybe even a tie. Dress befitting an important man with a federal mandate. In Dees’ words, “to come on the lock wall not fully dressed was a no-no. Man, you absolutely did not come on the lock wall without you were fully dressed.”

Walking man

Locking boats was about moving feet, particularly before the capstan mechanisms, which open and closed the moving parts, were electrified. At lock 7, the capstan had a gear ratio of 20 to 1. The handle for turning the capstan was five feet in length. According to Dees, “You’d just get on that [handle] and lean against it and start pushing, just keep your pressure against it and that gate soon, when it was full, it would start moving.” The capstan took six turns to open and six to close. “And if you let that thing get away from you, just fall as flat down as you can as quickly as you can. Oh, it will break you in two.” Once the gate-valves were opened, the chamber filled, and the upper gates opened, boats were lead in by bow-lines and tied off on the lock wall. Then the lower gate-valves were opened, the chamber drained, the lower gates opened, and lockage was complete. “Now, I figured it in a 30-inch Army stride, and I have checked it…you go approximately three-quarters of a mile” to lock one boat.

Most of the three-quarters of a mile walking distance involved some pretty heavy lifting, too. Prior to electrification, barges had to be pulled in and out of the lock chamber by hand—one barge at a time. “I have pulled many a one in and out. Those old barges that towed gasoline…I’ve pulled many a one.” Before interstates and four-lane highways gouged the landscape so that gas-stations could spring up at every intersection, barges hauled gasoline up the Kentucky for storage at the Camp Nelson tank farm. And before the railroad companies monopolized the business of hauling coal, barges carried dirty rock from the forks and Beattyville to facilities downstream and beyond.

At the height of his career, Dees was a very busy man. He remembers one day in particular when nearly 50 boats waited in the queue, and he once worked 23 hours straight on the lock wall, locking boats the entire time. He was ecumenical: “I’ve locked automobiles, I’ve locked geese. You wanna come through here in a tub? I’ll lock you through.”

The Kentucky at century’s end

At the end of his career, Dees would lock a dozen or so boats in a weekend, not exactly an eye-catching figure. But if we take a long-view, traffic on the Kentucky has been in fluctuation going back to the early years of impoundment and begs the question: Does a dearth of commercial traffic justify closing the Kentucky to everyone? According to the Army Corps of Engineers it does. They began looking for an exit strategy a half century ago.

According to the state of Kentucky and influential private corporations, however, the answer hasn’t always been unequivocally affirmative. Even as late as the mid-80s, some stakeholders in the debate, from both public and private sectors, saw the three-year lease agreement as a success and lobbied for continued seasonal operation of locks 5 through 14 (most assuming locks 1 through 4 would operate indefinitely). In 1985, Charlotte Baldwin, then-secretary of the state Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Cabinet, noted that usage had increased from 1,200 boats in 1981, the last operational year before the Corps’ temporary closure in the summer of 1982, to 2,458 boats in the summer of 1985, allowing some 11,000 people to pass upstream and down. Total cost to the state for lock-operation in 1985 was $55, 516, most of that sum going to pay lockmasters.

Lynwood Schrader, then-senior vice president of Kentucky Utilities and member of the Kentucky River Task Force charged with assessing the feasibility of state operation, calculated the total cost per boat at around $23, a figure much lower than what the Corps reported. But this discrepancy is not surprising given the Corps’ age-old desire to cut and run. Schrader also acknowledged that the real cost went well beyond a simple cost-per-boat calculation. “We need to keep the locks open to protect water supplies. If one of these locks needs repairs and the locks are inoperable, it would be much more difficult.” Many of the municipalities that rely on the river for their water supplies, including Lexington, also decried the Corps’ decision for closure. In the words of Ralph Conway (lockmaster at 8), “if anything should go wrong at lock 8, Lexington would be in real trouble.”

Despite protestations from citizens, municipalities, private businesses, and state legislators, however, the decision was made to begin closure of the locks in 1988, a process that took several years to complete. Lock men, like Dees, who can recall the heydays of Kentucky River navigation, are a dying breed. Of the last lockmasters originally employed by the Army Corps of Engineers only a handful remain: Dees’ uncle, Estill Thomas, at 98 the oldest living lock man (Lock 2), Earl Gulley, Jr. (Lock 12), Roy Berry (Lock 13), Charles Dees (Lock 7), and perhaps a few more.

The likelihood that there will ever be another generation of lock men on the Kentucky seems doubtful; doubtful, that is, as long as “profitability” in dollars is the sole measure of a river’s worth. But profitability in dollars has always been elusive to the many and exclusive to the few. Average Kentuckians living along the banks or within the watershed were always the real losers as tax dollar upon tax dollar was poured into improving the river. The “crowning” achievement was systematic impoundment, an undertaking spanning nearly a century from 1836 to 1917, and the real benefactors of this promethean effort were the timber and coal barons of Eastern Kentucky.

By accommodating these extractive industries, the state and federal government were, however, ensuring a degraded quality of life for people living along the Kentucky’s corridor and guaranteeing a significantly degraded river for generations to come. Once these industries petered out and moved onto rails, respectively, policy-makers and the Corps, for the most part, lost the political stomach to envision a new definition of profitability, a revised value system that pivoted not on dollars and bureaucratic cow-towing but on health and sustainability of the river for its own sake and for those millions of people living within its nearly 7,000 square mile sphere of influence.

But in 2011 who cares if the river makes money for this or that private industry? Obviously, not the state. So surely this river, the life-blood of millions past and present, and the seemingly inexhaustible provider of such profound solace, pleasure, and wonderment to so many people, the well-heeled and humble alike, is worth the cost, any cost of preservation. We need to be sworn in to action under a new Hippocratic oath—to do no further harm by the river. Considering the catastrophic costs of neglecting the Kentucky, of permanent “caretaker status,” particularly in a global ecological climate where political lines are already being drawn around water, maintaining, operating, and not altering the infrastructure already in place along the Kentucky seems like a no-brainer—a token investment to benefit the many. And this is no newfangled dream. Just ask any one of those lock men of old; they’ve been saying the same thing for quite some time.

Bobbie Jean Johnson

Thanks Wes for such a nice article about the river and about my Dad , Charles Dees, he so loved telling you the stories of his life on the river. It was a beautiful place to grow up and saddens me to see the run down condition it has become.