Labor, river care, lockmasters

By Wesley Houp

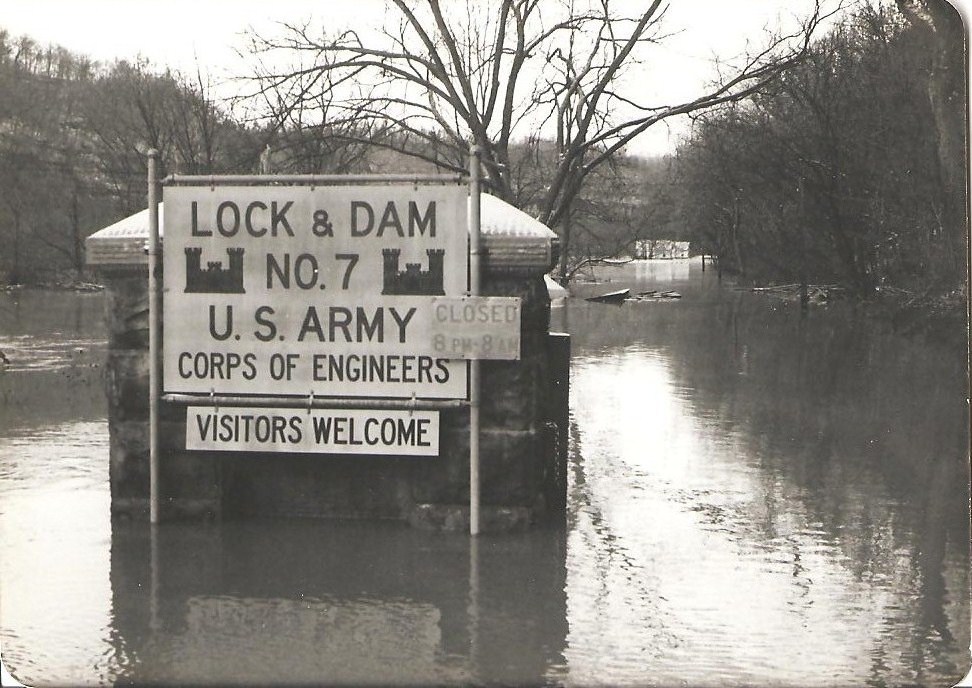

In 1985 the state signed a three-year lease agreement with the Corps of Engineers to keep Kentucky River locks open for recreational boaters. The agreement allowed the Corps to place locks in “caretaker status” should the state fail to assume full control by lease termination. Caretaker status, a curious if not ironic designation, would involve “welding the lock gates shut and discontinuing upkeep.” From 1982 to the lease agreement, locks 5 through 14 closed operations, and most of the lockmasters retired, moved on to other work, or took reassignments at the lower locks from Frankfort to Carrollton. In some cases, they moved on to other rivers and lakes.

Roy Berry, former lockmaster at lock 13 in Lee County, transferred to Taylorsville Lake on Salt River and finished out his career as lockmaster on the Green River. In his own words: “I sure didn’t want to leave the [Kentucky] river when I did. I didn’t think it was necessary to close the river. It didn’t cost them much money, wages were so low.”

Capstaning it to the man

After a career spanning three-plus decades, Chuck Dees, lockmaster at lock 7 in High Bridge, retired in 1979, two years after a federal district court decided in favor of a suit filed by Dees and 27 other Kentucky River lockmasters and operators demanding back pay. The efforts to reclaim the back pay were initiated in the early 1970s by Ralph Conway, lockmaster at lock 8 in southern Jessamine County. According to the plaintiffs in a 1974 letter to U.S. Comptroller General, Elmer B. Staats,

“[T]o enable the Corps to operate, maintain and protect the system 24 hours a day year-around with minimal personnel, a lockmaster and assistant were required to occupy and pay rent for quarters within each lock reservation. At least one of them had to be on duty at all times. This required the men, alternately, to work regular shifts plus standby duty up to 24 hours every day, averaging about 40 hours plus 40 hours or more standby duty a week per employee.”

The restitution, $2.5 million, was divided among claimants according to seniority. Dees, who began working on the river the year after his discharge from the Army in 1945, received the largest settlement award, $117,000 and Conway the second largest, $91,732. Conway believed that Dees’ award was the largest ever conceded by the federal government for back pay. The actual value of their settlement, however, was little more than $50,000 for Dees and $39,000 for Conway. The lion’s share, of course, was destined to cover federal and state taxes and legal fees.

The lockmasters felt they had “been shafted.” As Conway maintained, “If our claim has merit now, it had merit in 1972. We are being paid in inflated dollars and are not receiving any interest on the money due us. We are not getting any tax break because, with five-year averaging, I will have to pay still more taxes on the money I get.”

In 1976 the Corps deemed 24-hour surveillance of locks and dams unnecessary, and lock men were no longer required to reside on lock reservations or work longer than eight hours, thus eliminating the opportunity for overtime pay. But the Corps’ evasive legal maneuvers came too late to dodge the court’s snag. While both Dees and Conway expressed reservations as to the legality of the Corps’ decision to discontinue 24-hour surveillance, noting the strategic importance of the locks in maintaining water levels and supplies, particularly locks 7 and 8, both men called it quits on the river.

After the three-year closure, Dees returned in 1985 to operate lock 7, and in 1986 he began to oversee locks 5 through 9 for the state as part of the lease agreement. Asked if he would find it hard to leave the river again when the lease expired, Dees responded: “I can’t put this on my shoulders and carry it with me. Too many people do that, and they end up doing some slow marching and sad singing.” His final retirement in 1988 marked the end of an era, what Corps historian, Charles E. Parrish called “the nearly 200 year dream of a profitable Kentucky River navigation system,” which “now exists as a testament to the fact that great dreams often become disappointing realities.”

A family affair

For Charles Dees, being a lockmaster was more than a job. It had been a way of life for as long as he could remember. He was born in 1923 at Lockport, KY, where his father worked on a relief crew. Later, his uncle, Estill Thomas became lockmaster at lock 2, and his brother, Russell Dees, took over lockmaster duties at lock 1 at Carrollton. “Most of the lock men came from river families in the early days,” writes William Ellis in his river history. Like the railroad or the postal service, when it came to getting a job, who you knew was far and away more important that what you knew, and prior to World War II, who you needed to know was primarily another close family member—a father, brother, or uncle.

Earl Gully, Jr., lockmaster at lock 12 beginning in 1958, recalls an early encounter with Pete Hardin of the High Bridge Hardin’s (a river family employed by the Corps). “One of the first things Pete Hardin asked me was ‘How in the hell did a foreigner like you get a job with the Corps of Engineers?’” Pete Hardin himself benefited from the “who you know” system. Pete married Ruby Simpson, daughter of Bill Simpson, lockmaster at 7 through the 30s and early 40s. Pete’s brother, Cecil Hardin would become lockmaster at locks 3 and 4.

Dees’ life on the river spans from the era of steamers like the old tow, Chenoka, to the advent of diesel-powered engines. As a child, Dees remembers when the Chenoka would steam into port at lock 2:

“They had an old cook on there was named Jenny Carter. All of us kids, running around there, we had to go see the boat when it come up. I know back in that time, which was in the late 20s and early 30s, there wasn’t none of us I don’t guess over 10 or 12 years old. After all the men would set down to eat, Jenny would come out there and holler for us, or some of the deck hands. Everybody would help us, if we needed help, to get on the boat, and take us and line us up around this big table, and we thought that was the grandest thing that ever was. But it was back then, you know. And then, of course, they had plenty left over and fed all of us. Well, we met that boat religiously.”

The last packet boats passed up and down the Kentucky during Dees’ childhood as well. The last packet boat he recalls came up the Kentucky from Madison, Indiana on the Ohio.

“They made every whistle stop and picked up passengers and livestock and what-have-you. But this old drunk got on in Madison. Well, they started out, you know, going up the river and he goes around to get a ticket, and they went to him two or three times, and all he did…was just waddle his head around and just fall around.”

When the ticket agent asked the old drunk where he wanted to go, he replied, “I don’t know. I want to go to hell…” The agent told the captain, and the captain said, “Just let him off in Lockport, that’s the closest place to hell I know.”

In the first decades of the 20th century, over 50 packet and show boats plied the Kentucky, most taking passengers as far up as lock 9 at Valley View. “The old show boats, they’d come in and you’d hear that old calliope. This part of the country it’s ‘cally-ope’ but—you’d hear that thing for miles back in the hills. I know we used to go…to shows. But that’s all probably around early 30s, you know.”

Yes, Louisville does suck

Dees went to work for the Corps of Engineers in September, 1945 for the Cincinnati District. The next year, the Cincinnati District, which operated the entire Kentucky River system, was abolished, and in the spring of ’47 operation of the fourteen lock and dams was transferred, along with Dees and many other lock men, to the Louisville District. According to Dees, no one at the headquarters in Louisville was all that interested in an operational Kentucky.

The coal and timber industries in the upper stretches and above the forks had all but abandoned the river in favor of a less temperamental mode of transportation, namely rails. The Kentucky River, particularly above lock 4 and Frankfort, was all but dead to commercial traffic by the late 40s and early 50s (with the exception of several short coal booms, the last occurring in early 1975). So from the onset, the relationship between Kentucky River lock men and the Louisville District headquarters was marked with a palpable acrimony.

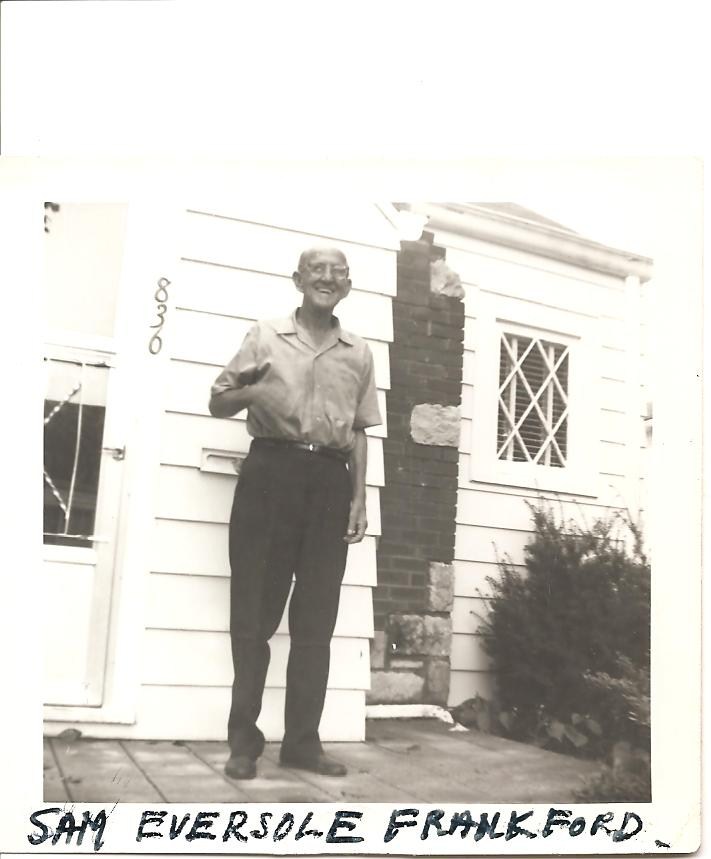

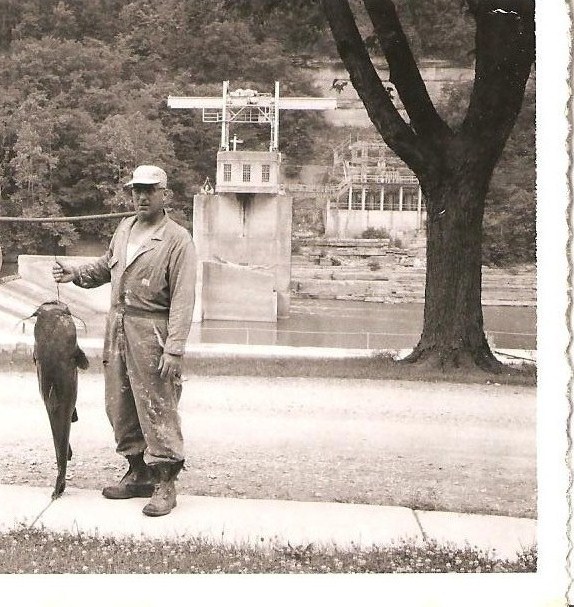

"Uncle" Sam Eversole, long-time superintendant of the Kentucky River and one of its champions. Photo courtesy Bobbie Jean Johnson.

These men and the ancient, slow-moving river they represented quickly became the unwanted step-children of a parent far more interested in caring for its favorite charges, the Ohio and Green Rivers. In Dees’ words, “how they could hate one thing as bad as they hate the Kentucky River is beyond me, and I know it never did one earthly thing to them. Never hurt them in no way.”

Early champions

It wasn’t always bad, though. Prior to dissolving the Cincinnati District, the Kentucky River and its lock men enjoyed more than several decades of genuine attention to needs. Even recreational use of the locks, which had been discouraged by the Corps prior to the mid-30s, found strong support among higher-ups, namely Colonel Roger G. Powell, the Ohio River’s first Division Engineer, who in 1936 maintained that pleasure boating on the Kentucky—in addition to barge, tow, and snag boat traffic—should not only be accommodated but encouraged. His advocacy led to a regular operational schedule, expressly directed at public use, so no locks were closed to navigation from mid-May to mid-October of each year. During these peak recreational months, locks could only be closed for emergency repairs and only at his express written consent. And to speed needed repairs, work crews would operate on a 24/7 basis. The river-using public, it seemed, had a champion in Powell.

Within the Cincinnati District, the Kentucky had earlier devotees as well. Prior to Powell, Cincinnati District and Assistant Engineer, Lucien Johnson and Kentucky River Superintendent, Sam Eversole, were keenly aware of needs along the Kentucky. The annual maintenance schedule they developed in the 1920s was based exclusively on empirical data. Early each year, the two would boat from Carrollton to Beattyville, stopping at each lock to gather information, hear the lockmaster’s own accounting of needs, and send their diver, Curtis Leitch, down with an ice-pick to assess the condition of the timber cribs and gates. They inspected lock houses and made note of any necessary repairs. During their one-way, 255 mile journey, they’d document all snags in the channel and sound the lock approaches on either side to determine any need for dredging. Assessment complete, they reported to Cincinnati for approval and a repair fleet dispatched to begin work each April.

To a man working 24/7 and raising his family on the river, this kind of genuine attention to his professional as well as personal needs inspired a sort of shared responsibility and pride that carried over to the communities nearby. Just as gravity pulls the river ever onward, the orderliness of the lock and dams was a positive energy emanating to the surroundings. Of course, being a lockmaster on the Kentucky never exempted anyone from the hardships of the times, particularly in these rural stretches of river bottom, but it was steady, guaranteed employment and the focused, comprehensive attention provided by men like Johnson and Eversole, one might argue, was of benefit to the entire watershed—natural and human communities alike.

In part two, Wes will look at the communities sustained by lockmaster labors, and what the state’s “caretaker status” means today.

Leave a Reply