In the end, sometimes good design does win out.

With the recent news that the city of Lexington shut down the Martin Luther King Viaduct for a week of “structural repairs,” it now seems official: Lexington’s MLK Viaduct will not be destroyed after all. The Brooklyn design firm SCAPE, home of certified MacArthur Genius Kate Orff, has altered its original designs for the city’s Town Branch Commons trail, which in 2013 had called for the city to demolish this key north-south connector.

In keeping the bridge, SCAPE and Orff will instead be following the good urban design ideas first introduced in 2013 by the low-rent, country-bumpkin, humanities college cast-offs who operate this Fayette Urban County paper shining on the screen before you.

Here’s the not-yet-reported story of how the local-class FUCers at North of Center hatched the idea—now validated by those world class geniuses up in Brooklyn—to save Lexington’s MLK Viaduct. And why you should be talking about this story of local gumption and forward-thinking design vision to your friends and your neighbors down the block.

Backstory

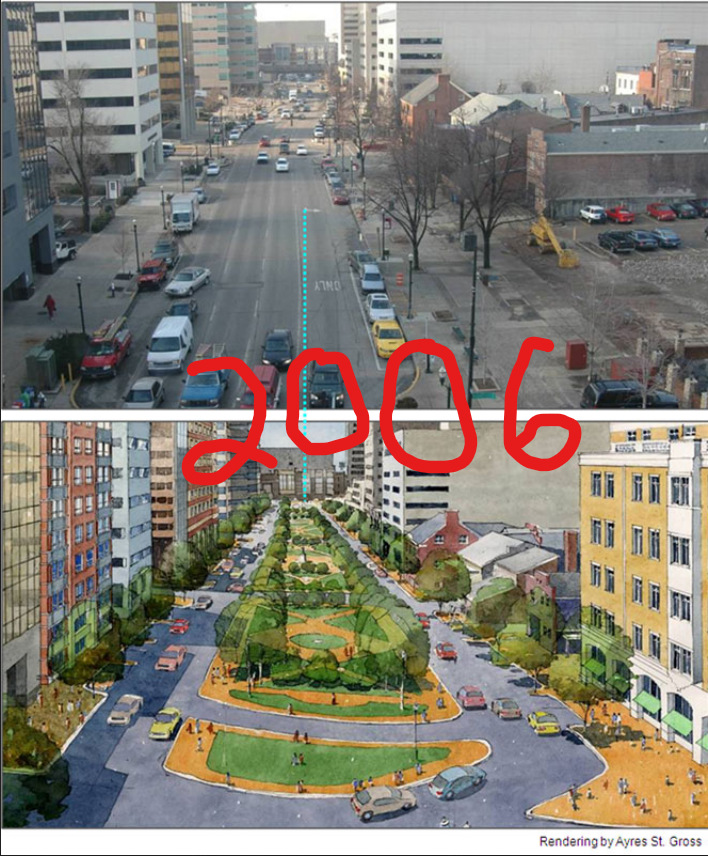

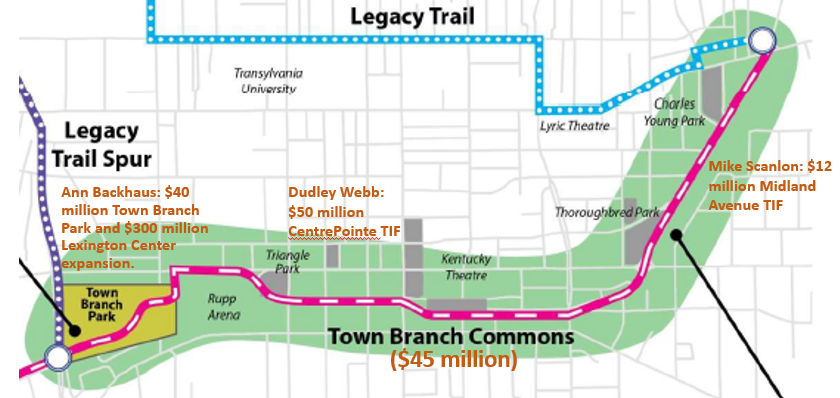

Since at least the Bush-era, the idea has circulated for an urban trail anchored around Lexington’s Vine Street and its stretch of uninspiring JR Ewing-era office towers. In October 2005, Lexington Vice-Mayor Mike Scanlon appointed an official city task force to “further define the existing vision for a ‘linear park’ on Vine Street.” That task force featured several council members, Lexington Downtown Development Authority president Harold Tate, developer Phil Holoubek, and former mayor Foster Pettit. (Editor’s Note: Scanlon and Holoubek own land along the East End portion of the now soon-to-be-completed urban trail they advocated for; Pettit’s son, Van Meter Pettit, heads the non-profit, Town Branch Trail, Inc., which has helped sell this development to the public.)

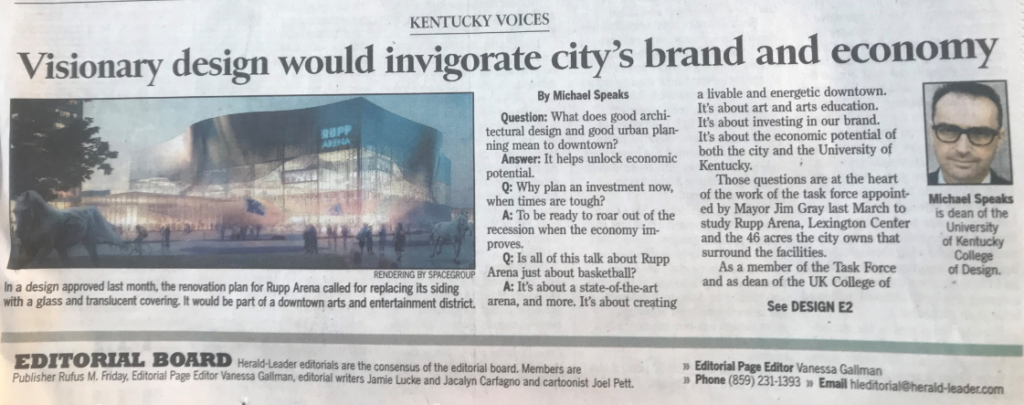

The Vine Street trail idea would re-appear in the 2011 report delivered to much fan-fare by the privately funded “Rupp Arena Arts and Entertainment Task Force.” That task force, which was not sanctioned by the city and did not include a single elected official, was ostensibly formed to greenlight what Obama-era Mayor Jim Gray saw as his signature political project: the re-skinning of Rupp Arena into a world-class urban destination.

To sell that unicorn project, the Rupp Task Force brought in “Master Planner” Gary Bates of the Norway-based Space Group architecture firm (also a former high school basketball player!). Delivered to an expectant capacity crowd, Master Bates’ #FreeRupp final report recommended that—in addition to coming up with $300 million to renovate Rupp Arena and build a new Convention Center—the city pursue a Vine Street urban trail to dead-end at the renovated development. (The trail was 1 of 2 that Master Bates flogged in front of the crowd to demonstrate how Rupp might be #freed; the other was a paint-on-the-road trail reaching around to the UK Student Center.)

A year later, 2012, yet another unelected body, the Lexington Downtown Development Authority (LDA), pulled from Master Bates’ #FreeRupp report in order to stage an international design competition. Now renamed “The Town Branch Commons,” the competition was for a 2.2 mile trail that would begin in the East End’s then-still-unbuilt Isaac Murphy Park, run south along Midland Avenue, then west on Vine Street…and finally end at a renovated Rupp Arena, Convention Center, and the brand spanking new Town Branch Commons park to be located just behind them.

(How prestigious was the LDA competition? Prestigious enough to land then-UK College of Design Dean Michael Speaks, a prominent member of the selection committee much quoted in local media and at Bell Court dinner parties, to an even better Architecture Dean-ship at a higher-ranked Syracuse University.)

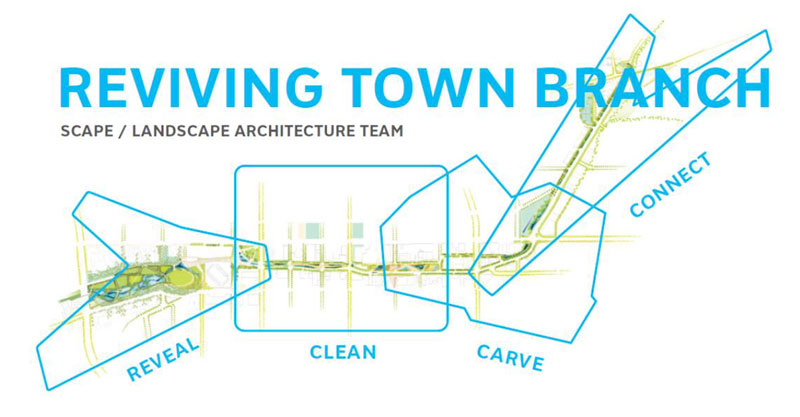

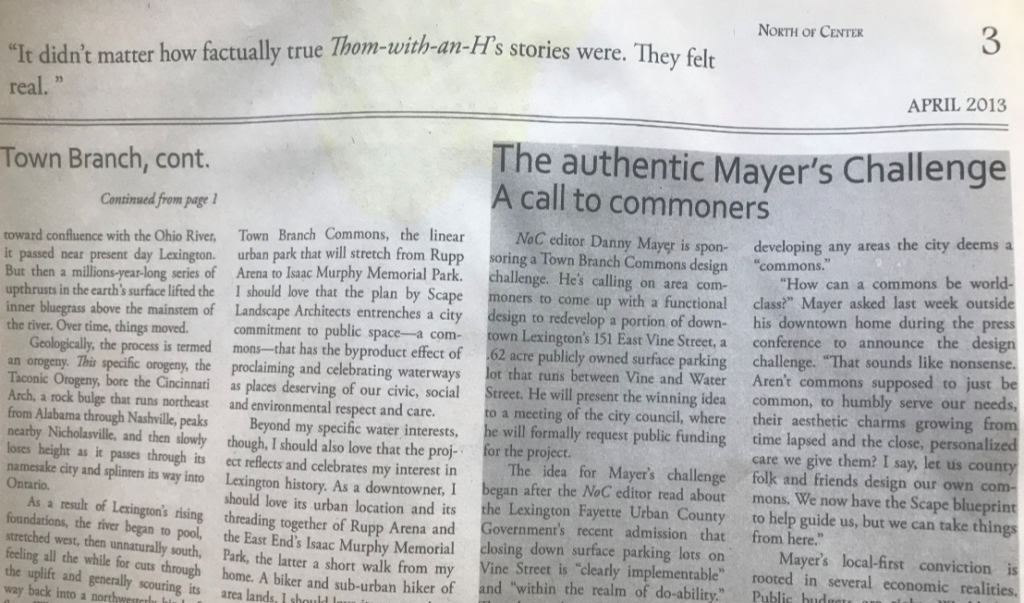

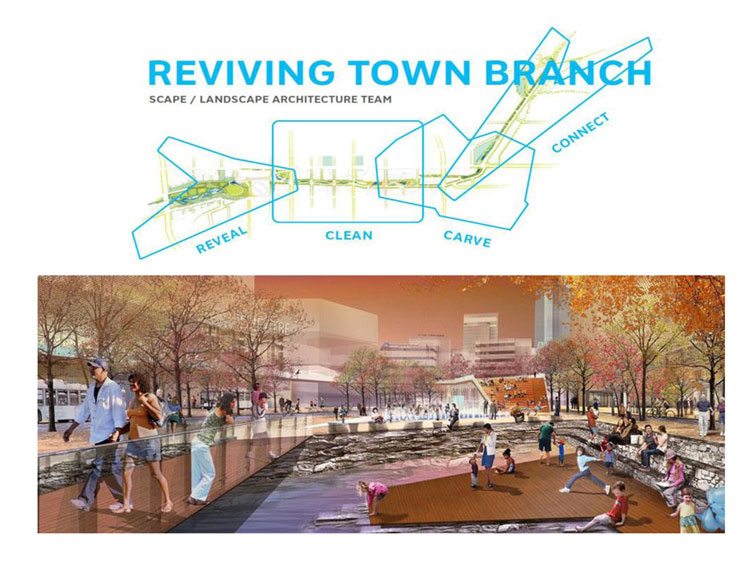

SCAPE’s design, which broke the proposed Commons Trail into four parts while making freshman-level gestures to the region’s limestone hydrology (and bourbon), won the LDA competition in early 2013.

As one might expect from so august a design competition—an international one! led by a smart dean!—the city’s MaLGA leadership went berserk, citing the Brooklyn landscape firm’s ability to get the region right.

Then-Herald Leader columnist Tom Eblen declared the New York plan as “the most authentic to Lexington.”

MaLGA design-leader Van Meter Pettit agreed, declaring the proposal “a fully realized appreciation for what is beautiful, authentic and unique about our city and its native landscape….Like a well-tailored suit,” the architect husband of Lexington Herald Leader progressive columnist Linda Blackford enthused, the Brooklyn firm’s proposal “looks and feels as if it were made for us and is not superimposed from elsewhere” (like Brooklyn).

Commons problems

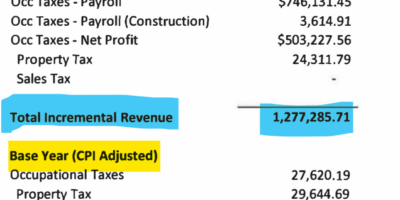

Despite the MaLGA accolades, there were always issues with the Town Branch Commons. As the public is slowly starting to realize, the world-class trail may go down as the most expensive road diet in city history. The city is paying a whopping $34 million per mile cost for a layup project that carves a measly 6 feet of protected bike/hike lanes from three already-fat 14-foot wide car lanes along Vine and Midland, a few city-owned surface-parking lots, and an already-established series of small parks that run alongside nearly a third of the route.

North of Center covered some of these issues with the Commons in our pre-2013 era. Mainly, they revolved around two related things.

First, a world-class Commons is a logical fallacy that will cost the city dearly. To pay the increased costs of a world-class SCAPE design that wasn’t much different from the local-class one developed a decade earlier, the “Commons” trail will need to be separated from the rest of the city park system, run by a newly created Town Branch Commons non-profit that seems destined to be endowed (unlike the parks in your neighborhoods) with $30 million in seed money for upkeep and programming.

As one 2013 NoC article put it,

World-class labor costs way more than locally engaged labor. In a world of competing desirable locations, authentic things produced from a studio in New York tend to be considered less authentic than authentic things made in the source location. Beyond the commercially dulling authenticity problem, though, the very complexity of world class designs also tend to increase costs, not to mention what complexity does to completion times (and repairs).

In addition to the problems clustering around the creation of a world-class and privatized commons, the Town Branch project had another problem: location, location, location. NoC noted that the 2.2 mile pathway selected for the Commons trail connected nearly $500 million in other city subsidies that were mainly focused on attracting tourists to Main Street. This sudden concentration of wealth, we suggested, would likely contribute to the ongoing gentrification of nearby northside communities (which has proven true).

Orff and her team did not create these community-borne issues with the trail, but they did benefit from and then seek to capitalize off them.

The MLK V and the Mayer’s Challenge of 2013

Along with this paper’s loud and persistent critiques, in March 2013, North of Center issued the “Mayer’s Town Branch Commons Design Challenge” as a way to both address and call community attention to many of the issues it had been raising. From the Page 3 announcement:

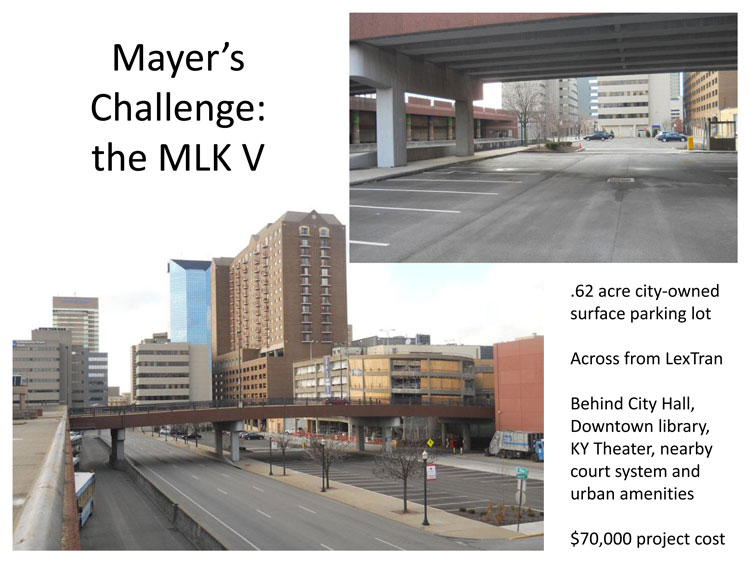

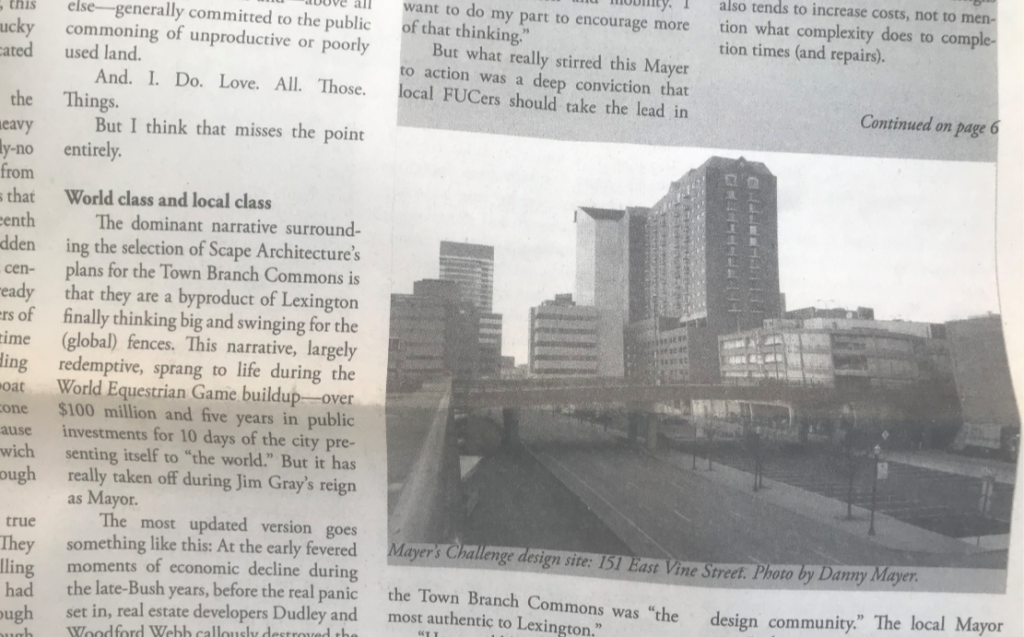

NoC editor Danny Mayer is sponsoring a Town Branch Commons design challenge. He’s calling on area commoners to come up with an affordable and functional design to redevelop a portion of 151 East Vine Street, a .62 acre publicly owned surface parking lot that runs downtown between Vine and Water Street in Lexington, Kentucky. He will present the winning idea to a meeting of the city council, at which time he will formally request public funding for the project.

What I wanted to know as a resident FUCer, initially at least, was how a body of un-elected blokes could come up with an idea—and then suddenly get access to the ears of our elected representatives and the pens of our local media, and through these vehicles, the funds from our public purse.

The $75 million world-class, Brooklyn-made, authentic SCAPE design for the Lexington Commons rested, after all, on the twin pillars of a 2011 “Rupp Arena” study issued by a Norwegian design firm and paid for by a privately-formed citizen group that was actively campaigning for a $300 million public investment in a basketball arena…and then a second, follow-up, 2012 decision made by a 5-person international design panel that was crafted and paid for by a different group of unelected city leaders. (This is Kentucky, of course; the white-collar members of these two groups were accordingly inbred with each other.)

In 2013, four years into running my own start-up, completely volunteer, northside newspaper whose 60+ on-time issues regularly addressed city design and development issues, I wanted to know: could any ol’ FUCer expect this SCAPE treatment? How exactly would the city value local-class design if it emanated from some scruffy low-rent college cast-offs who, unlike the Brooklyn geniuses given the $75 million keys to our “Commons,” actually lived and worked and biked and hiked and bussed and fucked and paddled here?

The NoC Mayer’s Challenge targeted the big gaping design flaw in the heralded SCAPE design: the demolition of the Jefferson Street and MLK Viaducts. SCAPE’s reasoning: it wanted “the viewshed.”

Nobody in this horse-and-buggy town seemed to disagree.

To NoC members, however, who regularly biked and hiked the viaducts in order to cross between their northside homes and the University of Kentucky and Bluegrass Community and Technical College, whose bar hops with other area residents from West Sixth Brewery to Country Boys necessitated a crossing of the Jeff Street viaduct, who saw a great amount of other city territory needing transportation upgrades and only a very little funding to go around, the SCAPE imperative to demo its way into a “viewshed” came with great future community cost and more than a few immediate missed design opportunities.

The 2013 NoC competition focused on the intersection of SCAPE’s “Carve” and “Clean” sections of their Town Branch trail proposal, essentially the territory beneath the MLK Viaduct that the geniuses planned to destroy. Instead of paying money to bulldoze the bridge for a tricked out set of “public stairs,” as SCAPE initially proposed, the Mayer’s Challenge project required that the MLK connector bridge be included in the design–an asset to leverage rather than an eyesore to take down.

In the next post, I’ll examine why the MLK Viaduct (as well as the now-destroyed Jefferson Street Viaduct) are such important Lexington infrastructure for non-auto downtown transport–many factors more important than viewsheds– and then detail the October 2013 NoC presentation to City Council of its #FreeLexTran design plans.

1 Pingback