A story of the late Holocene

By Danny Mayer

“This is the only story of mine whose moral I know. I don’t think it’s a marvelous moral; I simply happen to know what it is: We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.”

Kurt Vonnegut

July 8, 2012, the day the story broke, it was hotter than shit. 103 degrees in Lexington, 15 above the historical average, the last of an 11 day stretch of day-time highs exceeding the norm by over 10 degrees.

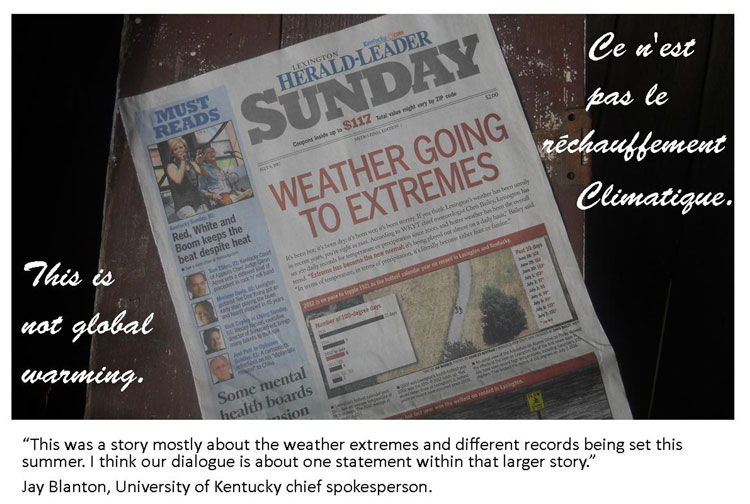

The news came in a series of staccato blasts appearing on the front of the Sunday Lexington Herald Leader, twitter-feed data blocks that covered the page like some rocks in a well-stacked, precariously tall, dry lay wall.

WEATHER GOING TO EXTREMES screamed the coping stone in super-size bold font. Extreme has become the new normal a blunt red splotch of text declared. “2012 is on pace to topple 1921 as the hottest calendar year on record in Lexington and Kentucky,” went the caption to a photo of parched grass lawn at the University of Kentucky Arboretum. “We might be dry right now,” declared some words above the image of a flooded street, “but last year was the wettest on record in Lexington.”

A sub-heading, “It’s not cold,” contained two bullets:

• 3 of Lexington’s 10-least snowy winters on record have occurred since 2000.

• No winter cold weather records have been set since February 1996.

My favorite, Red, White and Boom keeps the beat despite heat, is more flyrock than structure, technically not part of the WEATHER GOING TO EXTREMES story block, but telling nonetheless.

On July 8, the news was clear on one thing: bluegrass area weather had turned chaotic. Of the 491 words of text spread across the approximately eleven different data bits that detailed this crazy weather, “extreme” appears four times in three different information streams. “Extreme” cognates, words like record, most, swings, and unruly, appear in abundance, as do extreme-projecting “est” terms like hottest, wettest, snowiest. All told, the data streams rely upon at least 20 textual references to “extreme” to call attention to the decade-long shift into wild, warmer-trending weather.

July, as it turns out, would be a watershed month in a watershed year for discussions of chaotic and extreme weather. The month would find climate journalist Bill McKibben informing readers of Rolling Stone that May 2012 was both “the warmest May on record for the northern hemisphere” and “the 327th consecutive month in which the temperature of the entire globe exceeded the 20th-century average, the odds of which occurring by simple chance were 3.7×10-99, a number considerably larger than the number of stars in the universe.” Record breaking forest fires, which had already burned through New Mexico in April and May, in June and July would threaten several Colorado mountain towns, the US Air Force Academy’s Colorado Springs among them. In the Midwest, July saw residents still mired in a month’s long pattern of crop-killing extreme heat and drought; in the northeast, widespread flooding. On the weather channel, anchors were beginning the slow, casual introduction of some new words into the American lexicon, derechos and superstorms, names given to weather patterns so large and powerful that they caused immense damage across entire regions.

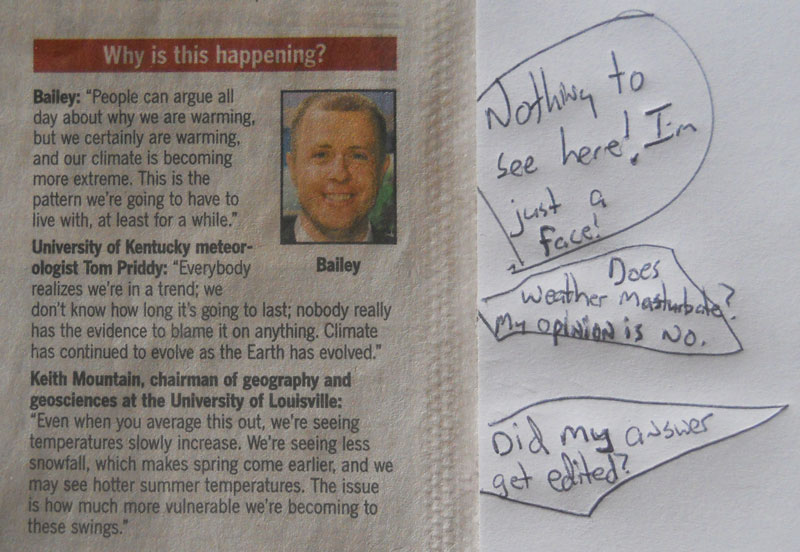

Amidst all the national chatter about abrupt and extreme meteorological occurrences, the real story breaking in the Herald Leader on July 8 had everything to do with what was not said, with what lay off- page and out of sight. In all the fear-inciting dispatches on “extreme” weather, the word-string “global warming” makes not one appearance. Tucked into the bottom right of the page, appearing as a sort of foundation stone to the interlocked data, a text block asking “Why is this happening?” offered possibilities. But no, on paper on July 8, 2012, the Herald Leader’s three credentialed experts were all in agreement: we don’t know why we’ve had such extreme, warm-trending weather.

The weather man said, “People can argue all day about why we are warming, but we certainly are warming.”

The University of Kentucky professor declared, “[N]obody really has the evidence to blame it on anything. Climate has continued to evolve as the Earth has evolved.”

The University of Louisville geography chair deflected, “[t]he issue is how much more vulnerable we’re becoming to these swings.”

On July 8 the news broke that my regional newspaper, still the primary source of everyday information for close to half the state—an important shaper of regional and statewide dialogue— has not a clue about global warming. On July 8, as I was about to find out, the news was beginning to break that the University of Kentucky, our Commonwealth’s flagship institution of higher learning, civic responsibility, and research production, is unable to discern whether humans are the primary cause of global warming, an inability that places it, both politically and intellectually, to the right of the Pentagon, a growing body of fundamentalist Christians, and Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson.

Feedback loops

To understand anthropogenic global warming is to open oneself to an avalanche of data. Climatologists record temperatures, droughts, floods, changing jet streams patterns, and then run them through sophisticated computer models. Oceanographers chart sea rise, ocean currents, fluctuating albedo rates. Glaciologists track shrinking ice sheets and increased releases of pre-historic methane into the atmosphere. Entomologists observe migrations of insect populations into new ecosystems; epidemiologists the creep of tropical diseases into formerly temperate climates. This doesn’t even take into account the reams of data covering the human geologies of climate change: our economic patterns of accumulation and waste, our landscape architectures of a carbon-burning culture, our social histories of extractive imperialism, our political deficits in leadership, and educational ones in knowledge.

To particularize and better draw out connections across vast sets of climate data, scientists often invoke the concept of feedback loops—climatic changes that amplify or reinforce other changes. A warming feedback loop for the American West might go something like this:

Sustained periods of increased temperatures in the American Southwest intensify water evaporation, which, coupled with a prolonged several-year drought, stress Rocky Mountain and Sierra Nevada tree cover, ecosystems that account for between twenty to forty percent of total U.S. carbon sequestration. Southern-dwelling mountain pine beetles, recognizing an opportunity when it presents itself, follow this warming weather and migrate into new northern territories, where their life cycle needs decimate stands of lodge-pole pines. Victims of heat, drought, and insects, the dead and dying pine trees provide fuel for massive, historically unprecedented summer wild fires in states like New Mexico, Colorado, California, and Oregon, places where the fire season itself has increased by two months over the past three decades.

Not unlike the western blow-up fires that create their own weather systems, these feedback loops become autocatalytic. They feed each other. In terms of global climatology, these and other loops are transforming the American West from a net consumer of carbon energy (a sink) into one projected to become a net carbon emitter—a reversal of thermal energy sequestration that will surely exacerbate the increasingly hot, drought-like conditions amenable to further tree-killing insect migrations.

While feedback loops are most often used by scientists endeavoring to chart changes in the natural world, the term is also useful for understanding the social components of a globally warming world. Politically and economically, the most familiar loop might go something like this. Call it the Koch loop, after its most reviled practitioners—oil magnates, philanthropists, and quasi-media moguls Charles and David Koch.

A Koch loop might begin with the observation that ultra-wealthy global business people own all the globally-pillaging companies that contribute the greatest amounts of pollution to the atmosphere: oil magnates, coal barons, industrial scale consumer commodity purveyors (Coke, Apple, Wal Mart), masters of war, bankers, and other owners of businesses of extraction. Enabled by their wealth, these barons fund large numbers of conservative Republican politicians of dubious intellect and leadership skills, and then direct them to roadblock climate change-related government work that might do damage to their corporate bottom line.

Reinforcing this political loop, earth-warming activists point to how the Supreme Court’s Citizen’s United decision has allowed unlimited amounts of corporate money to funnel into the election process, which further enables wealthy businessmen to bankroll perfectly Neanderthal candidates. Increasingly, this same group of very rich people and businesses also own or underwrite many large national and global media outlets, whose news agencies—the mainstream media—employ shady right wing think tanks to control information and cast doubt on the legitimacy of global warming.

Between the purchased political, judicial, and media Koch loops, these titans of industry, Lex Luthers all so the story-loop goes, have successfully kept red blooded do-good Americans in the dark about climate change. Here in the country that has pioneered and exported the carbon-burning lifestyle as a rite of democracy, only about 50 percent of Americans believe that the Earth’s temperature is rising as a result of human activity.

But the Koch loop has a lot of “they’s” in it, and while I am sympathetic to it and acknowledge its power to alter world sentiment and contain attempts at change, foisting this country’s indifference and ignorance of global warming upon a small cabal of wealthy business owners (none of whom seem to live near us) seems a tall order, one that releases many of us from our own culpability. Taken by itself, the loop reinforces the belief that conservative institutions serve as the primary promoters of uncertainty and/or malaise about the earth’s warming.

Here in Lexington, though, the dominant institutions for creating and circulating poor information are understood as liberal: the university, the paper of record, and even (compared to the rest of the state) its liberal and progressive elected public representatives. We should consider other types of feedback loops.

Loop 1: UK is dumb

For at least the past decade, the University of Kentucky has spent considerable time and money branding itself as the state’s leading intellectual center, the commonwealth’s finest factory for the production of an educated global workforce capable of tackling the world’s great and small problems. The university’s most concrete educational pursuit of that goal, a rhetorical focus on the need to emphasize STEM (Science/Technology/Engineering/Math) learning, asserts the vital role the institution can play in helping lift up a Commonwealth population most often described (even by UK’s former president) as uneducated and poor. For state residents, the assumption has always been that—whatever its administrative or faculty faults or rising costs of attendance—UK operates as a beacon of shining educational light, a trendsetter in the midst of a backwards state. It is this built-in institutional authority that makes UK faculty highly prized as credible sources of information for newspapers.

When the Lexington Herald Leader asked University of Kentucky meteorologist Tom Priddy to weigh in on the question no doubt on most readers minds after reading about chaotic Bluegrass weather, namely “Why is this happening?”, they did so knowing that the built-in reputation of a faculty member working at the state’s pre-eminent university is that s/he is a knowledgeable, inquisitive, and fair-minded scholar of their field.

“Earth/Text/Wood/News, study 2,” a multi-media collage by Danny Mayer. Editor’s Note: captions are author’s and are solely the products of his overheating imagination.

In Priddy’s case, his front-page answer was surely brand-damaging for a state research university looking to tout itself as an emerging national leader in the STEM fields. At the very least, his words had to have delivered a shin shot to anyone valuing the scientific profession and its process of knowledge accumulation.

“[N]obody really has the evidence to blame it on anything,” the UK meteorologist stated. “Climate has continued to evolve as the Earth has evolved.”

First off, something I may not have made clear. Within the academic science world in which UK scientists circulate, the “debate” over global warming ended a decade ago. A theory that once naturally engendered a number of skeptics (as good scientists tested assumptions, wrote up results, and engaged in rigorous debate), is now nearly scientific orthodoxy, as unremarkable among scientists as the theory of plate tectonics. Since at least 1988, when NASA climatologist James Hanson testified before the U.S. Senate, scientists have only provided clearer and more detailed evidence that humans have been altering the earth’s climatology, mostly through our increased consumption of fossil fuels. As a quarter-century of data-gathering and testing has refined the understanding of how warming works, deniers, skeptics, and agnostics have slowly melted away. One of global warming’s most recent high-profile converts, UC Berkeley physicist Richard Muller, even went so far last year as to cite a start date for human intervention into the climate: 1750, or about the time the English colonial empire began to burn coal on an industrial scale. Currently, scientific opposition to the theory of anthropogenic global warming represents a miniscule 2-3 percent of the scientific profession.

Speaking as a UK scientist on the front page of the Sunday Herald Leader on the question of extreme, generally warming, weather, Priddy, like the other two experts the paper quoted, was certainly staking out a radical critical position.

But in Priddy’s case, the explanation was seemingly unique among disbelievers, almost comically so: the world’s first evolutionary meteorologist. Here’s my friend Matt (BA, University of Alabama) writing in an email to UK spokesperson Jay Blanton on Priddy’s apparent theory of evolutionary climates.

“Professor Priddy thinks that the earth and the climate changes are caused by evolution—his words. Evolution, to my untrained mind, is the complex process of species differentiation through natural and sexual selection whereby valuable genetic traits are passed along. The earth changes due to plate tectonics and other geologic forces. The weather and climate are changed by variations in atmospheric composition, changes in heat input and distribution, etc. I am fascinated by his iconoclastic belief that the earth has evolved, and is apparently merely the most successful progeny as the result of millions of years of lovemaking between Mars and Venus, our mountain ranges exist because they most successfully fill an ecological niche, and the weather and climate are extremely successful species of clouds.”

In other words, the characterization given by the UK specialist on the topic posits that extreme area weather is not caused by global warming, but by clouds fucking. For a reading Lexington public, the assertion actually makes us more stupid and, on the whole, worse-informed than had we read nothing.

Loop 2: The Lebowski syndrome

Priddy’s statement awoke in me what Matt Taibbi has elsewhere called “the ‘Holy fucking shit!’ factor.” It would begin a string of emails sent first to UK President Eli Capiloutu and later to UK spokesperson Jay Blanton.

As the issuer of my Doctorate in Philosophy, I am professionally tied to UK. I have a continued interest in ensuring the institution maintain its currency as a place capable of both educating Commonwealth residents and equipping them with skills for being good actors in the world. In part, this is because my own value as a certified UK product is connected to the university’s continuing ability to display and utilize its intellectual faculties. My email asked if Priddy’s position was a UK position, namely that the climate and Earth have “continued to evolve” like monkeys. And if it was not a UK position, I wanted to know UK’s position on global warming. Does the institution or its president, I asked, believe in the existence of anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming?

Though uncomfortable, my questions were not farfetched. As UK has moved away from its primary task of educating undergraduates (this activity getting outsourced to graduate students and the community college system), it has branded itself as an institution whose rank and file perform the valuable civic work of tackling the globe’s intractable problems of today and tomorrow. Since one cannot tackle a problem, like healthcare for example, if one does not believe in its existence, I wanted assurance in the face of Priddy’s public assertions that my alma mater was at least capable of granting anthropogenic global warming its ontology, its “this-ness,” its existence in the world. Surely, I thought then in the year 2012, at a time when meaningless scientific debate on the topic had moved on to academic considerations of whether the rapid environmental changes already coming our way constitute an entirely new geologic era, the anthropocene, I didn’t have to worry that my alma mater was still agnostic on the matter of humans and climate change.

Across a string of emails (some publicly available on our Facebook page for July 2012), Blanton made three connected arguments in refusing to state whether UK-the-institution believes in the science of global warming. The first had to do with the need for the university to remain silent on all matters of education and research:

“[T]he University – as an administrative or governing matter– doesn’t typically make statements about scientific or policy issues – whether that’s global climate change, health care reform or the efficacy of genome sequencing. The reason, I think, is pretty rationale. We don’t make university-wide proclamations so as to ensure that we don’t inhibit academic debate.”

The second placed Priddy’s statements in the context of his position as an academic debater:

“He simply gave his opinion as a subject matter expert in a field relevant to the story at hand. I trust you are not suggesting that the university should take an official position or prohibit subject matter experts from expressing their opinion, regardless of whether it is a majority or minority point of view. Open inquiry and dialogue, as you know and value, are at the heart of the university and its promise – whether the topic is climate change or the economics of health-care reform.”

The third was designed to advance university consensus on a policy of not speaking out.

“I think most faculty would prefer that the university, writ large or as an administrative entity, not wade into scientific debates or the state of postmodernism as that could be perceived as a potential infringement on academic freedom. Moreover, with all due respect, I don’t believe that stance, in general, is outside the mainstream – by any means – of what other universities do as a general proposition…[G]enerally, universities leave opining on issues of science, policy or the digital humanities to the subject matter experts.”

I am familiar with these arguments. They are the currency of liberal academics, particularly those in the social sciences and humanities, where fears abound over infringements, real or perceived, on academic freedom. Indeed, after reading our email exchange, even my former dissertation director—a former president of the Association for the Study of the Environment and Literature—defended Priddy on these same grounds.

Whether academic freedom is an ideal needing continuous defense in the modern university I cannot say, but its defense makes concessions. The first is to the very idea of critical research and open debate. In Blanton’s formulation, to disagree with a faculty member’s opinions—a term by definition that refers to unfounded ideas lacking research and forethought—equates to a limitation on academic freedom. In the case of Priddy’s theory of evolutionary meteorology as an explanation for changing bluegrass weather, it allows Blanton to go all Lebowski. Does chaotic weather occur mainly because weather evolves? Well, hell, that’s just his opinion, man.

Blanton’s trick is to conflate intellectual disagreement with lost academic freedom. In this academic equivalent of “fair and balanced” news coverage, Blanton holds that my university is, paradoxically, unable to make declarative assertions on what is the biggest “global issue” of our lifetime because of its commitments to faculty research.

Put aside for a moment the utter horseshit of his assumption that UK does not take policy or other positions that are at odds with individual faculty researchers—its commitment to supply side education and budgetary decisions to pursue national Top 20 status are among several decade-long projects that would fly in the face of the work of Marxist and other researchers on campus. Taken at face value, Blanton’s Lebowski rationale is perhaps the best evidence yet for the utter uselessness of our modern university system when it comes to operating as informed actors in the world. Hearing Blanton, UK’s detached agnosticism on the existence of anthropogenic global warming is both perfectly rational and structurally necessary for the university to continue operations as a state, national, and global leader in…civic and educational matters.

In part 2, Danny will focus on a third agnostic feedback loop, which he calls “UK in the community.”

Leave a Reply