By Michael Dean Benton

Bianca Spriggs has entered my dreams. No Hendrick, not in that way. It is her art and words that I have been dreaming about intensely over the last week. Let me explain how this came about.

A few months ago I saw an announcement by Transylvania University professors Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorva for The Lexington Tattoo Project. They had a dream of their own, a collective art project that would involve 250 participants tattooing onto their bodies parts of a Bianca Spriggs poem written to Lexington.

As an advocate of participatory and communal art, I was intrigued and read through the poem for tattoo options. We were told that we could make multiple choices, with the understanding that we may not get our first choice, that the tattoo would be donated by the artist Robert Alleyne (Charmed Life), and that we could choose where to place it on our bodies.

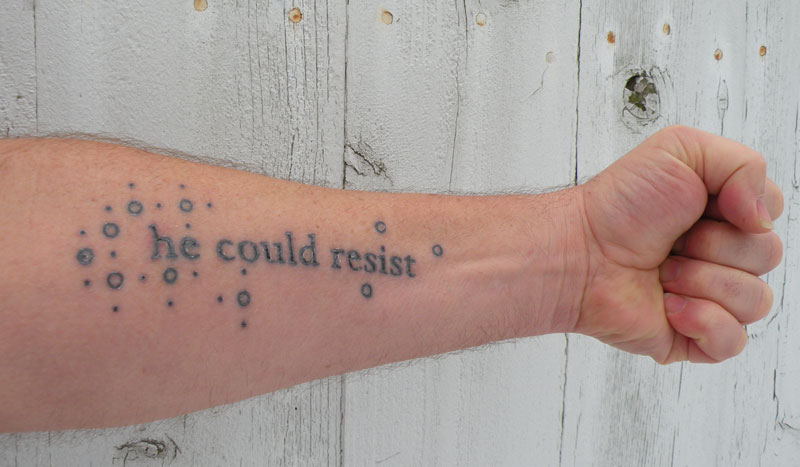

“he could resist”

Out of the 250 possible choices, only one word cluster spoke to me—or more accurately, seemed worthy of being inked onto my body. It was the phrase “he could resist.” These three words raised so many questions. What could I resist? Better yet, should I resist? And with no clear punctuation for the three words, the statement also seemed supportive, strength-giving even, telling me, yes, he could resist!

I knew this was the only choice that I would accept. It almost seemed as if Bianca had written the words for me, at this particular place and time, to prompt those necessary questions and to provide me strength in answering them. I entered just that phrase into the collective poetry/tattoo lottery and promised myself that if those words were not available I would not participate.

To my surprise, delight and trepidation, I was given my choice. Then the anxiety came. What was I doing? I’m 48 years old and about to get my first tattoo. I considered judicious body locations to have the tattoo placed—where would it easily escape notice?, I wondered—and settled on the back of my left shoulder where I could flaunt it when I wanted and cover it as needed.

But Bianca’s words kept reverberating in my head. I was in the midst of intense research for teaching a class on the contemporary global history of civil resistance. The histories of the incredible people and groups who put their lives on the line to resist oppression began to occupy my waking and dreaming thoughts. Always I would return to Bianca’s words: he could resist. Was it a challenge? And if so, what would be my response?

On the day I was to get the tattoo, I awoke from my dreams with the conviction that I could not hide Bianca’s words and still embrace the spirit of the project and/or my respect for their power as a guiding force. I decided that morning to place Bianca’s phrase on my left forearm, where it would serve me as a reminder and where, when people asked about it, I would be required to explain what it meant “to me.”

Through the tattoo, the poet’s words have begun to occupy a permanent place in my thoughts. They continue to affect me in ways I never expected and are shifting my understanding of art, creativity and language.

“A Noosed Life”

With all this on my mind I visited the Bianca Spriggs and Angel Clark art exhibition The Thirteen at Transylvania University’s Morley Gallery. I moved through most of the exhibition fairly quickly until I entered the video display for “A Noosed Life” (filmed by Angel Clark and Paul Brown, and edited by Paul Brown and Bianca Spriggs). I was creatively poleaxed; the imagery hit me so hard I had to sit down immediately.

“A Noosed Life” is a one and a half minute looped video of two actors displaying basic movements. The first (or the first that registered in my perception) is of a kneeling African-American woman touching slowly and intently around her exposed neck while gazing skyward. The image is overlaid with the white hands/arms of a man stretching and testing a rope.

The alternating and interweaving images allow us to situate the action as a mythic/collective story, something more than a limited tale of two individuals. It is the constant interplay between the woman delicately touching her neck while seemingly questioning “why” and the calm, murderous certainty of the man testing the rope. I had no idea where the video began or where it ended. Images and action simply repeated.

As with all great art, the video loop uncovered other experiences and thoughts. While absorbed in it, I returned to the first time I came across the James Allen book Without Sanctuary (2000), which documents the legacy of lynching in America through the perpetrators’ visual documents. I was in the middle of a crowded Borders bookstore during a holiday in Ann Arbor, Michigan. As I read through the book I began weeping uncontrollably and eventually collapsed onto the ground in the middle of the holiday crowd. Just as shocking and horrific as the desecrated, savaged bodies of Black Americans, were the smiling, joyous faces of White Americans in the lynch mobs. Eventually people asked me what was wrong, and when I shared Allen’s book some of them began to get visibly disturbed and agitated. My disturbance progressed to a point where the store security claimed the book and moved me out the door.

I’m of the mindset that we must recognize and confront our country’s dark deeds in order to understand how we can develop a better society. Most people know that racist lynchings took place in the U.S. (although few realize the extent or that they were not limited to the South), but they are often remembered as temporary lapses of collective sanity.

Like Without Sanctuary, “A Noosed Life” provides a counterpoint, prompts us to consider how lynchings were a socially sanctioned activity, used to keep a section of society in check and fearful, conscious tools of exploitation and oppression. The video does not show the face of the man testing the rope; it does not give in to the habit of producing a single, monstrous, scapegoat as a stand in for a collective guilt.

I wish I could invite Quentin Tarantino to Lexington, KY, and sit with him before “A Noosed Life.” I think there is much for him to learn in this video exhibition. Tarantino, and so many others, feel they must overwhelm our senses continuously in order to keep us entertained and buying their products. I would ask him to look into the actions of these two figures and to consider this video in relation to his spectacle of slavery as ahistoricized entertainment, one that evades any collective responsibility for slavery and any recognition of actual, real-life collective resistance to slavery.

I thought of other issues and events. I don’t know how many times “A Noosed Life” looped around as I gazed upon the motions of the two individuals. I touched the words tattooed on my arm and heard the words of the Civil Rights activist Anne Braden: “You do have a choice. You don’t have to be a part of the world of the lynchers. You can join the other America.” I began to realize one way Bianca’s words spoke to me. He could resist the urge to look away from the truth and he could resist the impulse toward a simply negative representation/recognition. He must face the horror of history, but he also must have the courage to create something better.

Before I got up from the video, Anne Braden’s comments on the civil rights struggle came to mind again: “What I’ve realized since is that it’s a very painful process but it’s not destructive.” He could resist and, in doing so, he would join with others that wish to do the same.

The Thirteen art exhibit will be on display through February 15th at Morley Gallery on the campus of Transylvania University.

Nancy Dreher

Your views are always so astute and observant and selfless, and I appreciate them tremendously. Are there any phrases/tattoo slots remaining on this project?

Michael Marchman

Nice piece.

W. Houp

Like the ink, bro.