The phantom map, part 2

By Gortimer T. Spotts

I awoke to the deep whir of a far-off tractor, Northrupp and the General still on the edge of sleep, and wrote in my journal “But a very small window is the dawn.”

We breakfasted, collected our brachiopods, crinoids, and other shoal-haul, stow-hoed, tarped up, and pushed off from the shallows at noon, the General once again leaving only his thin-sliced wake, Northrupp and I girding our boat-loins for the deadfall limbo just ahead. I’d completely forgotten about squeezing my vessel into this tight jam the night before, snagging and nearly losing the bucktail I’d been trolling on the off-chance of muskellunge. To our relief, the water—that we thought had risen and had indeed risen—had eerily not really risen, and we passed under with minimal grunting.

After a rejuvenating swim in the rock-bottomed pool just below the jam, and a quick-stuff from the Patokan-bag, Northupp and I clipped back to the mouth, where the General waited, staring through his laminated, flip-chart, genuine, revised 1975 edition of Navigation Charts, Kentucky River, Louisville District, Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army. “Hundred yards down river and we’ll flip charts, 30 to 29. Drowning Creek’s been a real good host, but lock eleven isn’t going to open up and just let us pass. No two ways around it. We’ve got a good paddle and even better portage ahead.” He paused, the sarcasm hanging in the willowy shade. “No sense prolonging the hardest hump to the hottest part of the day. Let’s push.”

We pushed but our pushing lacked any real sense of urgency. Northrupp was now wisely rationing the leaf, and we followed the shade as best we could, tacking inside to outside each bend, passing very little of cultural or historical note outside the ordinary riverscape—except for Richmond’s municipal intake, a somewhat impressive brick and concrete structure on the eastern shore, whose low electric hum briefly distorted the heavy roll of water over the spillway at lock 11 a quarter mile ahead.

The General sped toward the upper gate at the lock pit. We had, despite his warning, arrived at the hottest part of the day, just past three. The upside of lock-portage is segmented movement, though. You can’t do it all at once. You tackle one step at a time. For the record, our take-out wasn’t prohibitive. We carefully emptied each boat via rope, the General atop the wall and Northrupp and I tying on the gear below. Then we pulled each boat up the mud-caked crevice where the naturally steep bank met the sheer concrete edge of the wall.

Once all the gear and boats were up, the true nature of the job before us deflated any optimism and hope for an uneventful portage. It would be full of events, epic. General took off in long strides toward the north corner of the apron to gauge prospects of a straight-up haul the length of the lock and down the lower bank. As fate would have it, the neighboring farmer had corralled his horses on the lock grounds with four strands of barbwire, blocking easy access to the rocky approach below the lock and subsequently allowing a jungle of briars, nettles, and scrubby trees to obscure any descent to water. “Fucked again, lads, by the fickle finger of fate. No passage here. We’d have better chances daring the spillway,” the General motioned with a disgusted sweep as his foot slid into a fresh mound of horseshit. “Damned beasts” he muttered. “Isn’t this state-owned property?”

After 15 or 20 minutes of heated deliberation, we agreed it best to lower one canoe into the lock pit, 25 feet below us, to be used as a ferry for all the gear. The General would guide the ferry back and forth and stow the gear on the lower skirt-wall, which presented some dry concrete, and the nearest place to regroup. Once the gear was completely ferried, we’d lower the other two boats, paddle down to the skirt, and reload. The only way to negotiate the 25 foot drop was a rusted, bent, and water-worn iron ladder, inset in the crumbly, century-old concrete.

But despite the poor conditions, we executed our plan to the letter, a feat that inspired a sort of quiet pride in the General, a man accustomed to such organized and promethean efforts, and by 4:15 we stood, boats loaded, on the skirt taking in the hydraulic shock and awe of the spillway from our supplicant vantage 15 to 20 feet below. We glistened in the mist as the Kentucky crushed down on itself, we humbled acolytes, the river our disinterested and almighty deity.

The phantom map

In the next mile we started to separate, a natural paddling order based on each man’s craft, haulage, and relative desire to keep up, rounding what was supposed to be Noland Creek Bar. The General pointed out the diminutive mouth of Noland Creek, or what he thought was Noland Creek on the eastern bank (still in Estill County, one of the few counties the river actually transects). Northupp and I nodded in agreement. “Must be.”

“That means the bar must be submerged under, oh, a couple feet of water on the south side of the bend.” And with this last prediction, the General, Northrupp and I lost all sense of distance and place on “the map.” Had we indeed crossed from page 29 to…28? Or were we on another chart uncharted, an addendum, the lost map of poor Richard Calloway perhaps?

“Where the hell are we? Haven’t we passed that high ridge before?” I pointed incredulously to our northeast. We later discovered the Corps squeezed chart 28A in between 29 and 28, the “A” obviously representing “Apparition,” as what we thought was a five mile paddle to the mouth of the Red River turned out to be a ten mile slog, well off any map we could decipher, shushing any cheerful banter that might elevate our spirits. We entered the uncharted, serpentine channel, cuds churning and eyes scanning eith er wooded bank like white-knuckled surveyors of old, anticipating imminent ambush.

er wooded bank like white-knuckled surveyors of old, anticipating imminent ambush.

“That must be the high ridge separating the Red from the mainstream,” I called ahead to Northrupp and the General. “I believe so,” Northrupp called back. “So, the Red must be around the corner.” The General paused to consult the map. His eyes tennis-balled from map to viewshed for several seconds until he seemed to tire of ciphering, and he set back to chasing shade. “Well, I’m not going to kill myself in the process. It’s getting late, we have no good clue where we are, other than that we are heading downstream, and Upper Howard may or may not be the best place to camp anyway. I’m not counting on it. Let’s take it easy, find a place to eat, and then paddle late. All night if need be.”

Neither Northrupp nor I responded immediately. The new idea needed digestion, but my lumbar blurted out, “sounds good to me. No sense killing ourselves!” Northrupp said nothing, nocking his paddle across the gunnels and producing a glowing naval from his rucksack. “Want an orange?” He called back.

We pushed a little harder. I thought I recognized our position. “This must be Devil’s Backbone up ahead.” The General consulted the map without assurance. “No. No, we haven’t passed Thronburg Bend. It’s a real sharp bend to the east-southeast…or…is this Thronburg Bend?” We seemed to be bending hard to starboard. “Must be,” Northrupp snorted through naval pulp. He stood upright in his canoe. “Alright, men, time to leaf-up. If we’re lost on the river, we need to buckle down, hit the long-stroke and hump Upper Howard by twilight or we’re fucked. I’m not sleeping in my canoe tonight.”

Defiant, Northrupp hurled the spiral peel of his orange and dipped his paddle. The General and I followed suit, and before long we were breaking the viewshed of another bend. “Ah… Throngberg bend.” I heard the General coming up on my left. “This should be Thronberg… or… is that Rocky Face?” Again, the General flipped back and forth between his charts. “I don’t get this damn thing. I must have early onset dementia.”

Northrupp raced ahead, breaking a dogleg to the left. We pushed on harder, keeping him in pace. “This must be Thronberg,” Northrupp called back. “And to the east up there, that’s Strawberry Bend?” the General asked with a wave of his paddle. “At this point, I don’t recognize a thing. It’s all familiar for a moment then unrecognizable. Like that ridge. I’ve seen it four times in the last two hours, but then again I’ve never seen it before.” I was exasperated.

The Mouth of Red River

We pulled into rank. “Relax, gentlemen. To our right, Devil’s Backbone. To our left the Lord’s Hurt Locker.” Immediately to our left, half sunk and packed with silt, a vintage General Electric icebox. “Just like the one grandma Darla used to have.”

It was 8:00. We approached the mouth of the Red, each one of us desperately wanting to paddle in and explore the historic tributary, but none of us mustering the strength to interrupt our downstream momentum. On the Madison county shore, two boys and three men stood in waist-high fescue and peered down on us. Their voices were muffled by our paddle-strokes. We’d come 27 miles in a day and a half and hadn’t seen a soul, but we uttered no greeting. After our six-mile detour into uncharted bends, none of us felt like fraternizing. I caught the last snippet of the men’s conversation as we passed and entered Maupin Bend. “There’s no telling where they came from…” And then all was quiet again but for our weary strokes.

“Can we leaf-up again?” I called over to Northrupp. “Temperance, Gorty, temperance. Let’s wait until we make landfall and need the extra boost for night-womping.” He was right. Should we find a suitable camp on Upper Howard, we’d need every ounce of energy the Patokan bag could offer and then some. My biceps were flush with delirium as we passed the mud-slicked mouth of Noname Creek. The General, who had officially given up pace-setting responsibilities to Northrupp, whistled a lonesome tune somewhere in the growing shadows behind me. Northrupp glided to my right nearest the Clark County shore and at last bugled, “Upper Howard, men.”

Camp on Upper Howard

We angled starboard, entered the mouth, and eased our way up through snags and twilight. Bullfrogs gagged on their preambles to either side. On the north shore, a wide floodplain with newly sown soybeans angled up toward a lone hillock, and nestled at the crown, the silhouette of an old barn suggested only minimal human intrusion on the scene. “This field might be our best bet,” I heard the General suggest.

And indeed he was correct. After a quick paddle up the snag-filled stream, we turned back and found the small, mud-covered ramp cut through the high bank in the far corner of the field we’d passed on our way in. “Let’s pitch the tents above this ramp, boys.” So in the 10 o’clock twilight, we set about unloading, unfurling, and unwinding all the essentials. Within a half-hour, camp was up and running and we’d all changed into dry clothes. We decided to forgo a hot meal, delving headlong into core-warming spirit shots instead.

After an hour-long jaunt up the old farm road to the barn, we ambled back to the tents, said goodnight to the cosmic voyeurs, and retired to our sleeping bags. A pack of coyotes yipped somewhere over a distant hill. A great-horned owl wailed in the deep woods to our south, a chilly harbinger of sleep.

The night was racked with fitful dreams. I was set upon while boiling salt by a band of skulking savages, one hundred Shawanese led by chiefs Black Fish and Munseka. After a forced march across the Ohio, I was adopted by Black Fish, given the name “Little Big Head” and promised the hand of Black Fish’s oldest sister, Dirty Feathers, now a widowed matriarch approaching 50 years of age. She wore a necklace of human teeth, apparently her own. I awoke in cold sweats, mortified. “Northrupp, you awake?” I nudged his shoulder. He didn’t stir.

At daylight, we emerged from our tents. Only Northrupp looked rested. “Whoa, rough night in the sack?” he asked, noticing my exhausted expression. “Yeah, bad dreams. Nightmares even.” The General, with equally exhausted eyes, turned and muttered “you, too? I had awful dreams. A zombie had tied me to yon tree, uncapped my brainbox, and set in to licking the top of my thinker. With each lick my thoughts turned to static and my body writhed with uncontrollable twitching. Just fucking horrendous.”

“Wow. Sounds…bad. Sorry. I didn’t have any dreams. Slept like a friggin’ log. Want some bacon?” Despite his lack of concern for our sleep-travails, Northrupp treated us to a modest but delicious breakfast: thick slabs of bacon, fried eggs over easy, home-made torts with avocado slices and hot coffee. We ate gratefully in silence as the sun gradually worked over the tree line at our backs.

Dust-off at Muddy Creek

As we eased out to the mouth of Upper Howard, the General summoned us to the map. “I know we had our sights set on a Boonesborough take-out, but our little misadventure off the map yesterday chewed up a lot of energy and determination. I’ve been studying the map, and it looks like Muddy Creek might be worth checking out as an alternative terminus.” Northrupp and I were already familiar with Muddy, having washed up on the old Jackson Ferry ramp just opposite the mouth a year before at the end of two-nights’ journey down the Red River, a large bag of psychedelic mushrooms, and a four hour soak in the Kentucky where we were mistaken for flotsam by a family of overfed albino gorillas on a party barge, their oversized wake swamping both our canoes. “Ah, yes,” injected Northrupp. “Doylesville. A quaint little crossroads. If memory serves me, Doylesville Road crosses the creek not far from where we made camp, Gortimer.” I nodded in approval. A Muddy Creek take-out meant far less paddling today and more time to explore the environs by daylight. “So it’s settled,” said the General. “Muddy Creek it is.”

Doylesville appears prominently throughout the accumulated annals of Kentucky River history, mostly to underscore the Wordsworthian lament, “it is not now as it hath been of yore.” The once vibrant river community is today nothing more than a white, wood-framed Methodist Church backing up to Muddy Creek, a mile or so up from the mouth, and a spattering of farmhouses lining the serpentine road from Richmond. With each major flood of the twentieth century (most notably ’37, ’72, and ’78), Doylesville, like so many other communities along the river’s corridor, lost residents to higher ground.

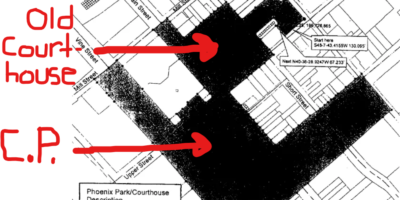

But floods were the last thing on our minds as we entered the mouth. The temperature hovered somewhere in the mid-90s, and we were hell-bent on finding a cool clear pool for a midday soak. We beached on the first shoal; I went ahead and called in the dust-off. Since we’d changed plans, our designated shuttler would need extra time to navigate Madison County backcountry to our coordinates astride lonely Doylesville Road.

We continued up the Muddy, in some places pulling our boats through inches of riffle-water, in other places returning to our paddles and skimming through the narrow, sometimes braided stream. With each slight bend, the water temperature dropped. We came to a deep pool directly behind the church. “I’m out.” Northrupp flopped over the side of his canoe, releasing the sigh that had been stewing in his overheated craw. “Well, no sense letting Northrupp have all the fun,” I said as I heaved-ho. The two of us soaked in the pool, staring up through a crack in the canopy. Not a cloud in the sky. The General, who’d fallen into a pensive and vacant silence, pulled his yak up to the riffle ahead our pool. He gazed up toward the church, then downstream for a long pause, seemingly indifferent to our sudden foolishness and banter.

“Something about this place reminds me of uncle Ranck’s closing remarks about Boonesborough.” The General took in the sky then grabbed a handful of creek sand. “The whole place, upland and hollow, has all the sadness of a deserted village, the melancholy charm of lonely nature, and the eloquence of an historic past.”

“It’s definitely deserted,” Northrupp harrumphed. “What’s eating you, General? You seem surprisingly glum for a man who’s successfully guided another expedition. Uncle Ranck was just romanticizing an early national moment in the hopes of stirring in legislators some sense of urgency for purchasing and preserving the grounds at Boonesborough for posterity. No need for glumness. We know he succeeded.”

The General sat in silence atop a layered limestone outcropping just above the pool. “You’re right, Northrupp, but it’s not loss or preservation of some distant past that bothers me.” He wanted to continue but broke off, standing to gain a better view into the indeterminate and encompassing void bothering his thoughts. We all swallowed back words for a few long minutes.

I broke the silence. “Remember the reflections of Felix Walker, accounting in old age his experiences with Col. Boone and Co. as they made way for ‘Chenoca’, the fabled Kentucky”:

We then, by general consent, put ourselves under the management and control of Col. Boon, who was to be our pilot and conductor through the wilderness, to the promised land; perhaps no adventurers since the days of Don Quixote, or before, ever felt so cheerful and elated in prospect; every heart abounded with joy and excitement in anticipating the new things we would see, and the romantic scenes through which we must pass… Under the influence of these impressions we went our way rejoicing with transporting views of our success, taking our leave of the civilized world for a season.

Upstream a car whooshed across the bridge. “I have ‘transporting views of our success,’” I added as if to lighten the mood. The General nodded but maintained his stare into the void. “Yes…yes… But the river goes on without us.” Northrupp turned in his watery repose. “The dust-off… Time to haul it up, boys.” Within the hour we were whizzing across the rolling savannah at 70 miles per hour, four lanes of interstate traffic stretching out in front and behind. No one spoke, our last words on Muddy Creek binding each tongue, until we crossed Clay’s Ferry Bridge and the General glanced down: “Behold, the Kentucky.”

Listen to Wes Houp covering two of Gortimer’s camp songs played on his Big Black Johnson.

Leave a Reply