Lexington finally invests in its world-historic waterfront

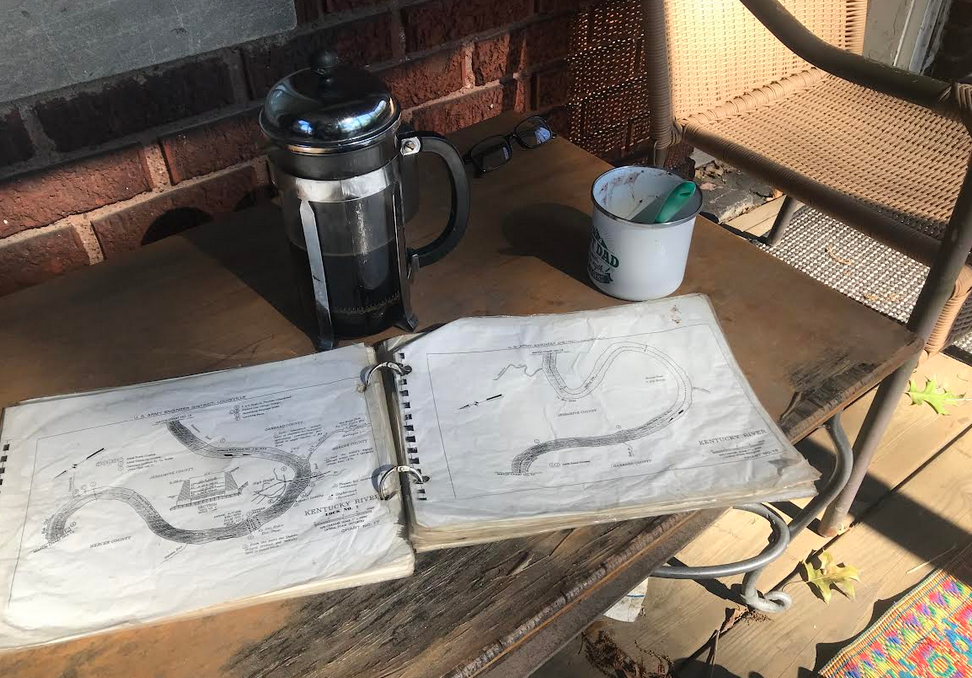

Between 2009 and 2013, writers for North of Center paddled the entire 250 mile mainstem of the Kentucky River, from Heidlesburg to Carrolton. Guided by an archaic Corps of Engineers navigation map once employed by an extinct species of coal and timber-filled river barge captains, our paddles were nothing short of magical.

We caught a firefly light show while sitting in a drenched field along Drowning Creek. At the mouth of Lower Howard, we held a frosty springtime luncheon inside the skeleton of a half-submerged towboat .

We floated past the mouth of Boone Creek under the radiant light of a harvest moon. Camped inside the cave at the foot of Devil’s Pulpit. Passed Laphroig draughts atop the Devil’s Meathouse.

Hiked Jessamine. Waded Paint Lick and Shawnee and Hickman and Clear Creeks. Skipped rocks beneath the capital building. Portaged oh so many locks and dams and the occasional lockmaster home. Many of these otherworldly trips appear in our online, and in some cases, just print, archives.

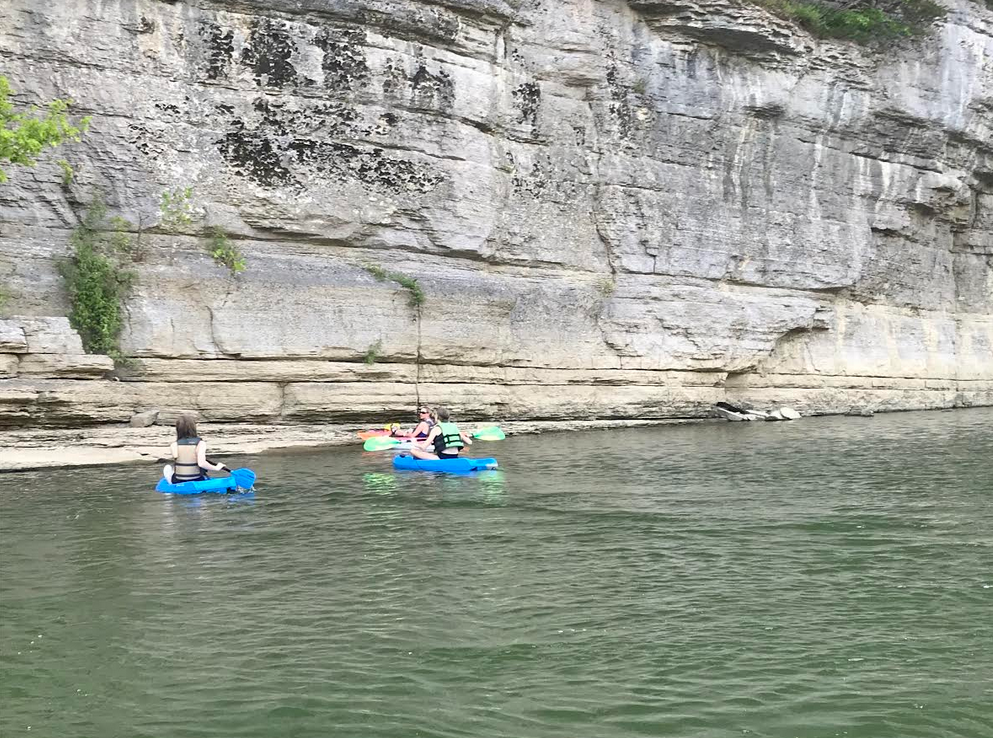

NoC‘s Obama-era paddles upon the Kentucky are one example of what VisitLex President Mary Quinn Ramer earlier this summer referred to as “outdoor recreation and adventure tourism.” Growth in this sort of tourism–our sort of tourism–“has been significant,” Ramer enthused, “over the past two years.” The VisitLex President’s statement was prompted by news that the city planned to purchase 30 acres along Pool 9 of the Kentucky River for a future public boat launch and park. The as-yet-unnamed park will be located along the southeast edge of Fayette County, below the I-75 bridge on Old Richmond Road and nearby the most excellent Proud Mary’s Honky Tonk and BBQ .

As long-time outdoor recreationists, we applaud the city’s purchase. Recent tourism trends aside, the stunningly gorgeous, ecologically distinct, mind-boggingly old, 100 mile inner-bluegrass stretch of the Kentucky River is perhaps the defining feature of our city and region.

The river here surrounds the city on three sides as it meanders its way through some of the oldest exposed rock on earth. The French naturalist Francois Andre Michaux, all the way back in 1804, would favorably describe Lexington’s upland “situation in the centre of one of the most fertile parts of the country, comprised of a kind of semi-circle, formed by the Kentucky River.”

The future park is sited toward the upriver, or easterly, portion of this inner-bluegrass palisaded enclosure, downriver from Boone Creek, on land that has been a center of faunal transit for many tens of thousands of years. Nearby archeological sites suggest the area has been inhabited by faunal-following humans for over 10,000 of these years.

Bull Hell Park

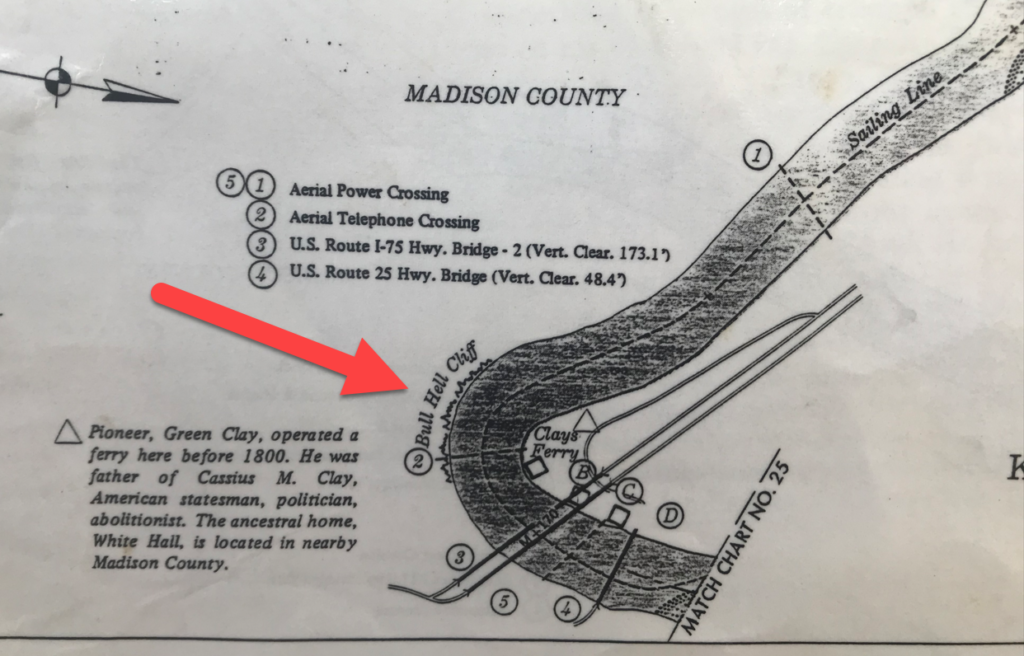

The city has yet to name the future park, but the guess here is that it will be known as some safe derivative of Clay’s Ferry Park. There are good recent historical reasons for choosing the name.

In 1792, the year of Kentucky’s statehood, a ferry was granted license to operate here, shuttling goods and people across the Kentucky River for a fare price. Here is the historian T.D. Clark with more on the site’s gringo evolution, from his 1942 Rivers of America series contribution on the Kentucky River.

[The Kentucky River] had cut its bed deeply into the blue limestone, but at one place a roadway drifted down the sides of the palisades, and the river crossing was called Clay’s Ferry. This crossing was named for…Green Clay, a big landholder and a prominent Virginia soldier and legislator, who had come west to the Kentucky country…

Once it was a point of departure for flatboatmen on their way to New Orleans. All the logmen from up the stream knew the ferry, and they looked upon it as a happy landmark on their difficult journeys downstream.

Thomas Dionysus Clark, The Kentucky

In the 1860s, Green’s son, Cassius, ceased operation of Clay’s Ferry to make way for a bridge that came to be known as the Clay’s Ferry bridge. This name, Clay’s Ferry, has also often been used to describe the small community clinging to the palisades that hem in ferry and bridge crossing.

As a potential name, Clay’s Ferry Park certainly makes sense. But, really, don’t we have enough Clay iconography around here?

NoC‘s choice–and the name we will use henceforth to refer to the park–is Bull Hell. Our name refers to the 250-foot high limestone palisades that rise directly across the river from the future-park. As with Clay’s Ferry, Bull Hell is also imprinted upon the Corps of Engineers navigation map, an indication of its importance to the barge traffic that floated Eastern Kentucky coal and timber to markets in the Inner Bluegrass and beyond.

And as with Clay’s Ferry, the Bull Hell name has a Clay connection. Here is more from TD Clark on the linguistic origins of the cliff-line:

Close by Clay’s Ferry was a second point of interest. Where the gray-limestone banks pushed up to a high point was a spot called ‘Bull’s Hell.’ The origin of this name is somewhat legendary, but pertains to the quick temper of Cassius Clay. It was said that he had a pure-bred bull which was difficult to handle.

Thomas Dionysus Clark, The Kentucky

On one occasion he tried to catch the animal; and when he was unable to do so, he ran it over the steep bank and smashed it against the rock shoulder two hundred feet below. When inquisitive neighbors inquired about the bull, the high-strung Cassius replied that he ‘had gone to hell,’ or at least he had gone to ‘Bull’s Hell’ on the Kentucky River.”

Bull Hell is a colorful though not solely uplifting story, but it rests upon an honest geology. Its high cliffline sits atop a deep fault line, part of a system of faults that criss-cross the Kentucky between here and High Bridge as the river, in the face of an ongoing millions-year-long tectonic uplift, struggles to regain its ancestral, 200-million year old northwesterly course. For paddlers paddling past Bull Hell, the palisade limestone here appears to be eating itself.

Up on the Lexington peneplain, our city thrums with Clay and Clay-like monuments that project a certain timeless moral certitude. Young and Carnegie Libraries. A Martha Todd and a John Hunt Morgan house. Ashland. Keeneland. The Joe Craft Center. Rupp Arena. Names stripped of deeds.

But what our North of Center paddles taught us, as we cavalierly floated a river that ran 250 feet beneath those Lexington uplands, was not timeless upland stability but its opposite. Tectonic orogenies. Great floods. Pirated watersheds. Fault zones. Floral succession. Erosion. Sacrificed bulls and buffalo. Locks, dams. Pillaged timber, plundered coal. Deeds stripped of names.

As NoC house poet Wes Houp would write in one of his 2012 trip reports, “We are deep in fault here, boys. Deep in fault.” In a fractured world, we would all do well to acknowledge this river-borne regional truism, and to celebrate our city for (finally) granting us public access to it.

These are just two among the many reasons why we should all hail Bull Hell.

Can’t wait to explore the area on water? Proud Mary’s has a free put-in already.

The palisades are stunning at all seasons. Grab a paddle, take a float.

New Jawn

One more thing, “Bull Hell” would be perfect — edgy, unforgettable, a name that just begs to be told to others, but for those reasons and more, it doesn’t stand a chance.

Get ready for Palisades Park or ThoroughPaddle Way or Kroger Wildcat Water Splash or JetSkisR’Us or something picked by an executive committee of some quasi-corporate, public-private, government-business, we-never-you, chamber-board-commission thingie.

Danny Mayer

Heh.

Come visit Kroger Palisades Park at Bluegrass Community Foundation’s Pool #9 on the Kentucky River!

Bull shows daily in the summer.

New Jawn

That was a great read. Thanks for putting things into words.