Be George Bailey

By Beth Connors-Manke

The transcendent part of It’s a Wonderful Life is supposed to be George Bailey’s realization that his life, disappointing as it was to him, had positively impacted others’ lives. As viewers, we’re supposed to empathize with George’s struggles and be warmed by his hope and reconciliation at the end. However, when I watched the film again last week, the part that resonated the most wasn’t George’s redemption; it was the economics of housing.

If you haven’t watched the film yet this holiday season, I’ll recap: George feels the building and loan, which he inherited from his father, is a stone around his neck, but the thing that keeps him in the business isn’t careerism or a desire for stability. It’s that there is so much injustice related to housing in Bedford Falls. The villainous Henry Potter has immigrants and other working class folk over the barrel; as his tenants, they are at the mercy of his exorbitant rent, which keeps them from getting ahead. They can’t save; they can’t buy their own homes; they can’t start their own businesses. Potter benefits from the slums he creates; he profits from hamstringing the finances of “the rabble,” as he calls them. The building and loan, on the other hand, allows citizens to borrow money to build their own homes and get out from under Potter’s heel.

And then the Depression hits. George forgoes his honeymoon because there’s a run on all the financial institutions. The newlyweds end up in a run-down, vacant old house because that’s the only thing they can now afford; George had offered up his own savings to stabilize the building and loan.

I could go on, but I think you get the point: as in the film, we’re in the midst of historic economic injustices rooted in the housing market—a situation rigged by not just one small town Henry Potter, but by a whole network of financial “experts.” And, as in the film, we’re presented with a moral choice: do we make housing affordable, or do we let the market perpetually inflate rent, let it mandate that families are put out of their homes, let it drown homeowners whose mortgages are upside down?

Obviously, this is a huge crisis that must be addressed at national and international levels. However, Lexingtonians can attend to a small piece of the problem (and in a George Bailey-like way): support a local Affordable Housing Trust Fund (AHTF). Supporting a Lexington AHTF is projected to cost the average person $15 per year. George floated much more than that to his Bedford Falls customers and neighbors when they rushed the building and loan. His sacrifice kept the entire community more stable and, in the long run, more prosperous.

Background on the AHTF

In 2008 BUILD (Building a United Interfaith Lexington through Direct Action) and other local organizations proposed an AHTF to rectify some of the housing inequities in Lexington. At BUILD’s request, in spring 2008 then-Mayor Newberry agreed to put together a taskforce on an AHTF. The commission issued a report by September 2008.

As its yardstick, the AHTF Commission defined affordable housing as “housing that requires families and individuals to pay no more than thirty percent (30%) of their income for housing and housing related costs.”

Of the rental households in Fayette County, more than 45 percent currently pay more than one-third of their gross household income on rent. This means that these households are not affordably housed. Worse yet, 18 percent of renter households pay more than half of their income for housing, leaving these neighbors in danger of becoming homeless, according to the Central Kentucky Homelessness and Housing Initiative.

At a March 2011 council meeting, Commonwealth Economics, a firm hired by the Council to study the fiscal, economic, and social impact of an AHTF in Lexington, presented their study on the issue.

“Housing trust funds are dedicated sources of revenue to help low- and moderate-income people achieve affordable housing,” Commonwealth Economics writes in its report.

“In most cases, a government agency—usually an existing housing agency—administers the housing trust fund and awards grants and loans to local governments, non-profit developers, for-profit developers, and, in some cases, individuals, for a variety of low- and moderate-income housing activities.”

The study found that a local AHTF would, on average, produce approximately 470 housing opportunities each year, along with 150 new construction jobs and 320 rehabilitation projects.

The research also found that “more than 363 new jobs will be directly and indirectly supported by trust fund investment.” Additionally, “more than $43.3 million of direct, indirect and induced economic activity will be generated from trust fund investment.”

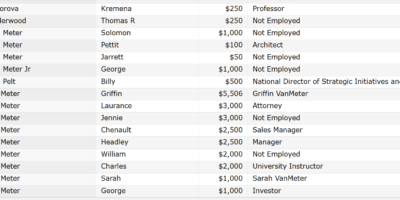

After almost five years, the volleying of the AHTF question between various Council committees, and much “studying,” Council is still generally squeamish about standing for affordable housing in Lexington. The councilmembers who have committed to this form of justice are Chris Ford (District 1) and Steve Kay (At-Large). If your councilmember is not on that list, you’re encouraged to call his or her office and press the importance of an AHTF.

If you’re enjoying your holidays in a warm and festive home, your neighbor should be, too.

Leave a Reply