Elkhorn to Lockport, part 2

By Danny Mayer

“Thank you for showing me Gest today, the two lock houses facing Cedar Creek those bureaucrats will soon raze.”

My breath flashes vapor at each line. Nearing late-afternoon on the Kentucky River, the sun has only recently asserted itself in the sky, somewhere near Stevens Branch on pool 3, four river miles past. This would have been before the portage at Gest, Lock 3 across from Monterey, and before the exploratory amble up the hill to see the two Gest lock houses in decay, the result of a strategic decision by the state and its people to abandon upkeep of grounds and water. Before the ham and cheese on bread, before the piss breaks, before reloading and shoving off, one-by-one from the remnant pad below the lower lock gates, to ferry back into the main-stream (eddying overnight at Severn Creek) on our way to Lockport.

Say, three hours ago.

But still, my breath leaves me heavy and wet. In the sky, the January sun is shining bright and dry. Here on the water, the current up from considerable winter rains earlier in the week, things still feel damp.

In honor of Monterey’s poet laureate Richard Taylor, I am reciting—“Ad infinitium ex-temporanium,” I have exclaimed just moments ago off-page in a fit of Jim Beam exuberance—the poem “Letter to Chenoca (Lock 3, Kentucky).” By now, the current has pushed us out of sight from Gest and the frothy mouth of Cedar Creek, but the decaying houses are still on our minds.

“Hunkered atop this lock, space closed by caved ceilings ten feet and higher, chill wind shushing through frayed wallpaper and yellowed bits of history, holding tightly inside from out—looking in from under the spear-shaped eaves, it all comes back to you.”

Wes, whose father spent time as a child in the 1940s at the Gest lock houses, catches my drift and cuts in.

“Tales where Dad laid up playing Indians with friends, kids, who hung in the attic to watch the river go, to play Huck along the banks. Not perfect, but other worldly.” He pauses for a second, looks briefly back upriver. “Lock life, fattened with water, kept the bluegrass lubricated.”

Scribing this now, I should remind you: none of this has gone down exactly this way. By late-afternoon on the Kentucky, this one or any other on that river, the likelihood of Wes and I achieving any non-rote coordination in our endeavors, much less harmonizing on a riffed Richard Taylor poem, is—while quite certainly possible—not very probable. In fact, Taylor has only intruded into this story in the past couple weeks, late-March, as I’ve placed my non-existent notes and dampened memory of “night on Severn” alongside my harried research of the area. Heck, I don’t even like Jim Beam. But then again, skimming along a river like the Kentucky, with its abandoned channels and pirated watersheds, its prehistoric gar and grown-over river communities, its upthrusts and its erosions–a veritable river of revisions—who’s to say this fourth draft of our trip, this new channel etched into the public record, isn’t as accurate an account as any.

Wes and I converge on our harmony.

“These jaunts we take to scraps of found timber, to beds of fossil coral—“

“To Elkhorn!—”

“To Gest!—”

“To Brown’s Bottom!—”

Then Silence.

Wes, Lyle and I stare blankly at Keith—on his first trip, a rookie—sitting hitched in his canoe at the edge of our floating armada, vaping, giving us the “did I miss something?” look. Our eyes linger on our friend only a moment, and then, Lyle joining in now, we return to our tailored piece.

“This lust to get the primal depth of things, it strikes us finally why. To reconstruct an unconstructed state, the touchy balance of waters we might measure before we gurney, so that as we sink, our hands might judge the depth.”

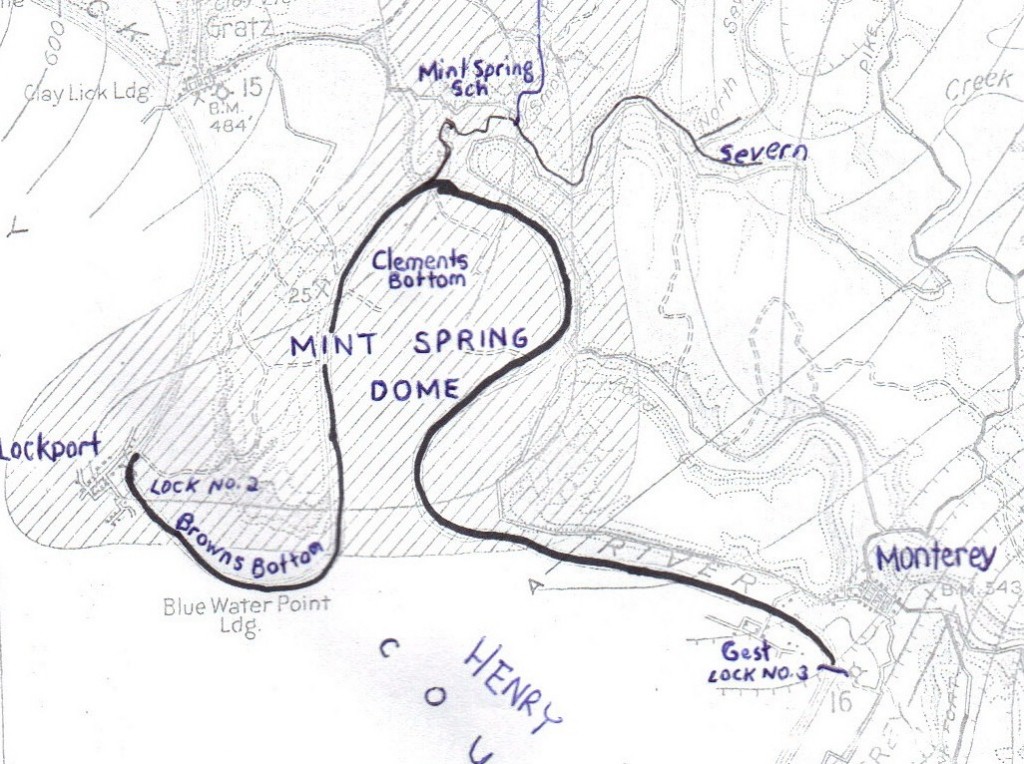

Image from Aereal and Structural Geology of Owen County, Kentucky. Map by J.J. Wolford, M.S. Chappers, and S. Withers, 1931, completed under the directorship of Kentucky State Geologist Willard Rouse Jillson.

Past events

We close our score to the sound of buzzards, Kentucky eagles, really, circling the heights above us on river-left. We are at the turn to Clement’s Bottom, at a temporary confluence of the ancient and current Kentucky Rivers.

In earlier times, about six million years earlier at the beginning of the Pliocene epoch, the river here bent left, to the west, before looping back around to present-day Lockport. Several million years later, a series of late-Pliocene orogenies—upthrusts in the earth’s crust that literally lifted the bluegrass savannahs from their foundations—knocked the ancient Kentucky from its entrenched meandering path. Here at the entrance to Clement’s bottom, the local result of that orogeny, the Mint Spring Dome, caused the Kentucky to cut an entirely new bed. Instead of curving left and to the west, we modern paddlers of the Kentucky follow its arc to the right—east—threading between Clements’ Bottom, the Severn Creek watershed, and Brown’s Bottom.

To put it straight, this ancient upthrust pirates the rest of our paddle. We spend our last two days rimming the Mint Spring Dome in search of a low spot to scour our way beyond. In typical Kentucky fashion, to find that low spot, that knick in Mint Spring Dome, we will trace a near complete circle, paddle 6 river miles and cover 2 days in order to travel the ¾ of a mile to Fallis, located on the back-side of Clement’s Bottom, an alluvial suburb of the Kentucky River town of Lockport.

On the water, Wes elaborates to the group.

“Before the Pliocene uplift, the bluegrass was nearly completely flat. Like a rivulet cut into a dirt path, the Kentucky etched its bed into the surrounding savannah. When its banks flooded, the flatness of the surrounding area meant that alluvial sediment was dispersed along a broad floodplain. Willard Rouse Jillson, in my estimation our state’s most esteemed geologist, calculated that flooded sediment reached a distance of 3-5 miles from its banks.”

“When the bluegrass orogenies came, they lifted the Kentucky’s bed, staunched the river’s flow, and ultimately caused it to overspill its banks. These overspills eventually cut an entirely new bed as the river, desirous as always to ensure proper laws of gravity, sought out new courses around (and through) the new impoundments recently sprung from the earth’s crust. Jillson claims these upthrusts ‘brought about the rejuvenation of the Kentucky River.’—Say, do you all want some Zwack?”

Wes looks at each of us. With why not shrugs, one by one we grab the Hungarian liquor and take warming swigs. With the bottle making the rounds, our trip’s geology lesson concludes.

“Beyond the bluffs to the left—if we were to go that way, which of course we can’t now—is the abandoned Pot Ripple Channel, first discovered by Jillson—” and here Wes points to me—“on May Day, 1943. Josie’s birthday.”

Night on Mint Spring Branch

We come into Severn’s mouth with a feeling of relief and satisfaction. The last hour on the mainstream, we have paddled hard into stiff headwinds, the water at times resembling a choppy bay. Passing under the truss bridge spanning Severn Creek, roughly half-way around Clement’s, we ease up and begin reconnoitering lodging options. Lyle’s preliminary Google-Earth scouting of the area suggests possibilities on the large bottom beyond the Owen County municipal straw, and farther up, any flat land that strikes our fancy on either side of the creek.

These things are always touch and go. One never really knows until doing it how far up a creek one can paddle. Water levels fluctuate according to watershed and season. Long shoals, virtually hidden via internet scouting, could appear too close to the mouth. The day could be getting late. You could be tired. There’s also deadfall. Private developments. Four-wheelers. Beavers.

So after a couple bends on Severn when Lyle says, “not far beyond this looks to be pretty secluded. From Google, it didn’t appear as if any houses would be within eyeshot,” we all know not to get too excited just yet.

After passing a low-lying, muddy, braided bottom, we make first landing on the downstream side of Mint Spring Branch. The exploration reveals unfavorable camping conditions, but we stumble upon a series of rock foundations and empty cabin hulls that follow the spine of a 300 foot knob, the remnants of an abandoned community that must have grown up around Howlett’s (later Clement’s) landing near the mouth of Severn Creek. Official history, in this case a recently written history of Owen County, makes no mention of the community. Its presence, so far as I can tell, only comes in map form, a reference to a Mint Spring School on a series of 1930s-era oil and gas maps.

Our initial hypothesis of the Mint Spring ruins, based on the stacked rock foundations and log walls, dates it to early 1800s. Upon closer observation, though, the settlement looks more like a historical conglomeration. The ruins appear to be in some state of reconstruction. Parts of the old rock foundations seem restacked, and in some cases fresh-cut stone, which has a greater appearance of blue along its fracture line, mixes with the old.

While the downstream plot doesn’t meet our overnight needs, just across the way, the large wooded bottom on the upstream mouth of Mint Spring Branch, meets them quite well: flat, dry, good view, somewhat sheltered from turbulent weather and snooping landowners, and with an abundance of downed wood.

By the time we set up our sleeping quarters, work up a fire, cook and consume a delectably muddy river rat stew, and pass around all night-time sharables, the sky has grown cold. Last night’s clouds kept our temperatures in the high 30s, but the clear heavens tonight let the cold rush in. I had hoped for enough energy to take a night-walk down a trail that led (we thought) to an old post office located further up the Severn Creek valley. But by 9:30, I am tired and ready to hit the sleeping bag.

Everyone seems to agree that tonight will be an early one. “Just staying warm standing around this fire,” Keith observes, “is adventure enough at this temperature.” I am in my sack under the tarp by 10:00 P.M., and drift in and out of sleep to Wes reciting to Keith and Lyle a final campfire poem, another Taylor concoction, this one titled “Severn Creek.”

“For the third spring we trek the disused county road,” Wes intones. “Deer prints pressing ground made soft by yesterday’s showers. In gray tiers, hardwoods rise up toward the cedared bluffs. The luscious glut of creekwater riffles through us intimate as breath.”

“It’s early. Spring purrs its lime among the branchtips—not yet an exclamation. The trout lily has performed its bloom, but the Dutchman’s-breeches are still furled like silken flags. Fire pinks still smolder hours shy of floral combustion, the beds of bluebells we hiked miles to see already basking in the bottoms…”

A winter silence descends over us all. As my world darkens, as I fade out for the night, the last thing I hear is Lyle breaking the silence: “Shit. We need to get back here in the spring.”

Good morning weathercock

I awake, stiff, to the sound of Lyle’s voice falling upon me as a morning sun that lights the fading night. Up early as always, Lyle has forsaken his normal morning walk in favor of re-stoking the fire. From a slant-eyed peek out of my sleeping bag, I glimpse him sitting Indian-style on top of his PFD, singing Jethro Tull to the embers.

“Good morning weathercock, how did you fare last night? Did the cold wind bite you? Did you face up to the fright?”

I force myself to unzip and exit into a biting cold. The world outside our tarp has become glazed with frost. My boots, which I’d forgotten to put in my sleeping bag to keep warm, are cold blocks of stitched leather. Begrudgingly, I throw them on and tend to my morning chore: water filtration.

This was my first with this crew. My rat friends here have an instinctual distrust of the safety of Kentucky waters. They prefer six-packs of half-gallon water jugs. Our truce, successful it will turn out, is to allow me to pump water from any creek residing in a watershed downriver of the MTR line. Here on Mint Spring this morning, the handle on my pump is cold, and my hands sting with each turn. But the empty High Bridge jug eventually fills, and I return to camp for breakfast (rat stew, add Wes’ eggs), shareable pass-around, pack-up, clean-up, another pass-around and load-up.

By day 2 on trip 9, things have their own familiarity. Even Keith, rookie that he is, pipes in with a Taylor contribution of his own. Fishing a book from his dry bag, he says, “Gentle-rats, here is a final poem for our final descent into Lockport. Ahem…’The River issues a statement regarding its watery ethos,’ by Richard Taylor…’Don’t look to me for virtue, for high-minded feats, or elevated speech that flows in a stream of lustrous silver—when cutting is my nature, meandering my path.’” “If at times I stray from my banks, diverge from narrow limits, know that motion is my credo, that at heart I’m inclined to trade in sediment, traffic in silt.”

“Here! Here!” We all cry out.

“Virtue I leave to creekside pillars, to chaste limbs of the sycamore, small hands of the quivering birch…to towering cottonwoods, whose rectitude goes untested.”

Upthrusts and rabbit shit

On our paddle out, we pass by the Mint Spring settlement again. Catching it from this angle, one can see how vast and subtle a reconstruction is taking place. Somebody apparently has a rock-stacking compulsion. And so, the old Mint Spring Branch trails start to get reclaimed; a certain order, an infrastructure, begins to appear on the old bed.

Seeing the rock-work, I can’t help but think of another Kentucky river writer—Gurney Norman. One of the defining images of Divine Right’s Trip, Norman’s picaresque counter-cultural travel-adventure that ends in the coal-damaged mountains of Eastern Kentucky, is that of the lead character, hippie hero Divine Right (DR), employing his uncle’s method for rehabilitating family property ravaged by coal-overburden and erosion. DR’s daily task? Grow rabbits to create rabbit-shit food gardens, a steadying of the land. It’s one of the more beautiful and hopeful visions of anthro-geological upthrust.

Of course, that’s just story-timing. It took me a little longer to put all this together. It wasn’t until just past Fallis on the other side of Clement’s, where Pot Ripple Creek now comes into the mainstem that things started to cohere. And even then it was more of an elemental free association, a fluidity almost. Josie and Jillson upthrusts; Mint Spring branches and Pot Lick abandonments; Gest houses and Lockports. The coherence bit, the bed into which to put all these, the maps, these arise a little more slowly, and are always weathering.

Listen to Lyle’s morning version of Jethro Tull’s “Weathercock.”

The editors would like to instruct all readers to purchase a Richard Taylor book from your local bookstore to read the actual poems we’ve debauched here. Our choices: Fading into Bolivia, Stone Eye, and Earth Bones.

Julie shelton robinson

I would love to visit the old clements areas. I am a Shelton/clements from the Roger and keturah line. Jule Shelton Robinson. 1968julierobinson@gmail.com

Joe Sams

I grew up on the farm next to lock 3 on the up-river side in the 1960s. My grandmother grew up in Clements Bottom and attended the one-room school that is still there. As for the lock houses, I remember when the lock keepers and their families still lived in them and they were very well kept. I drive through there about once a year and have great memories of a different time. Thanks for the great article.

Joe Sams

Wes

Fantastic rechanneling of a crystalline-cold paddle, Dano. Richard Taylor reigns as ghost-emeritus for that stretch without doubt. Lyle’s version of the Tull classic is, well, better than the original. Deft picking, sweet vocalizations!