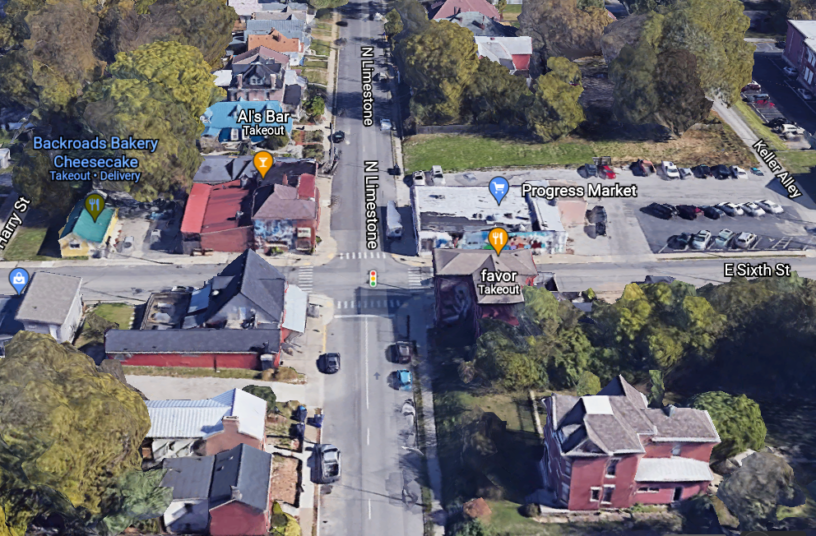

I moved downtown in the Spring of 2008. While there are any number of reasons why my wife and I decided to move here, Al’s bar on the corner of Limestone and Sixth figured prominently in many of them. I am sure I am not alone.

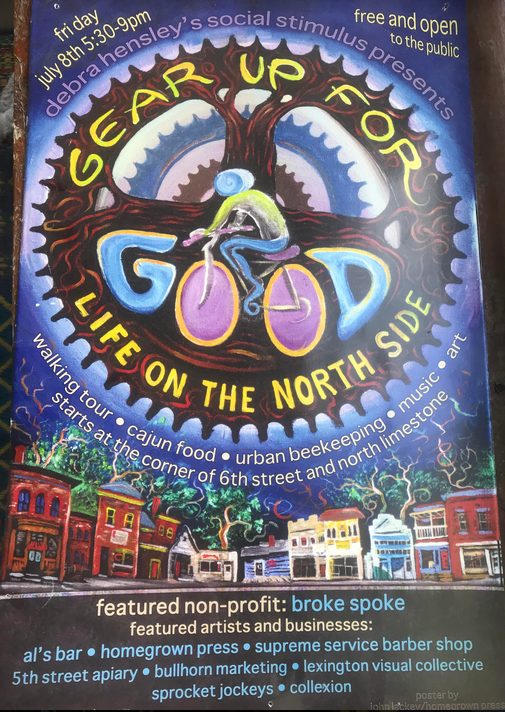

Al’s had it all. Local beef. Cheap beer specials. A free jukebox and pool table. Music nightly. Poetry monthly. Poster art plastering the walls. Fundraisers for Kentuckians for the Commonwealth and other righteous orgs. Comedy nights. Youth orchestra nights. Hip hop nights. Bluegrass nights. Some nights found you crammed near a stage; others, slouched in quiet conversation over an empty bar.

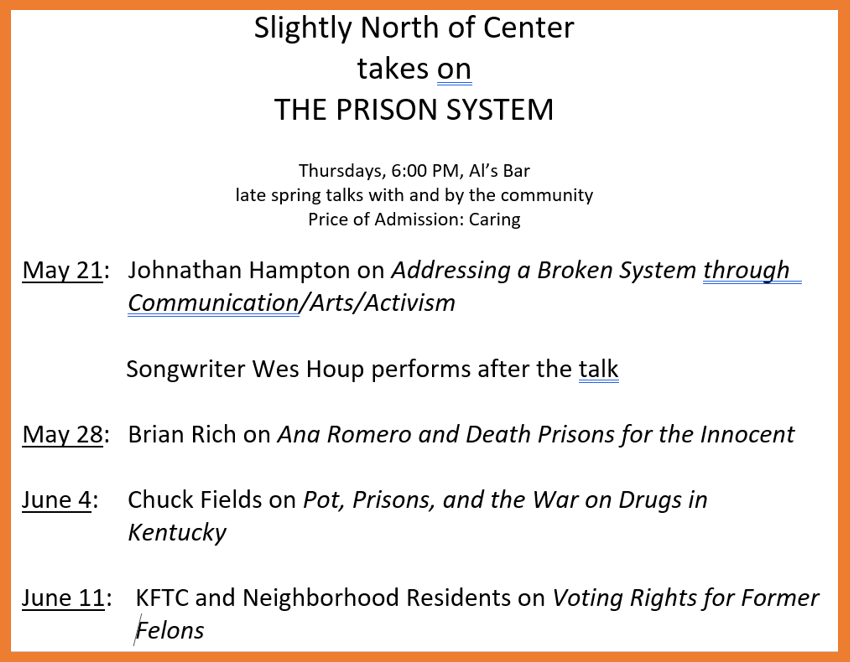

I jumped right in, running a healthy bar tab while staffing a summer Free Market in the Al’s parking lot, comprised mostly of excess veg that some friends and I grew on a few acres in Keene. Inside, I hosted sparsely attended talks by area residents on topics ranging from the U.S. prison system and the death of Ana Romero (the undocumented Lexington immigrant found hanging in her detention cell on the eve of her deportation), to guerilla gardening and Kentucky River history.

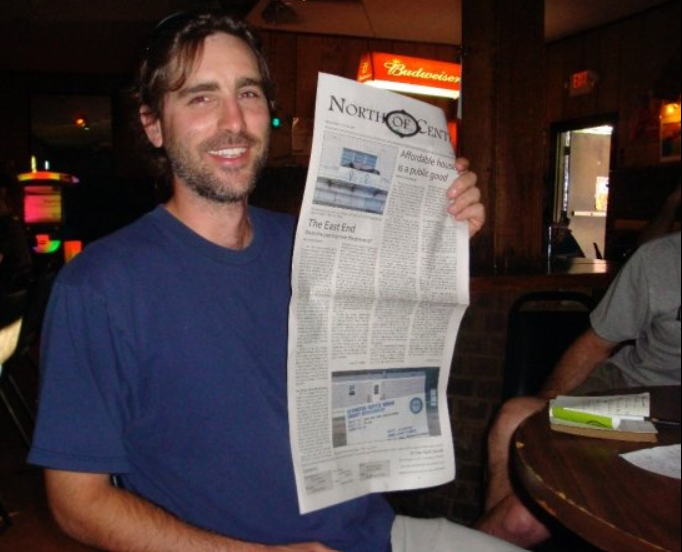

A year later, the bar would become North of Center’s unofficial headquarters during its first (print) incarnation, a center for our north.

In the early years, it was easy for me to imagine Al’s as a certain type of urban utopia, a cultural and social mixing ground of diverse populations. True, the bartenders were all white female college grads, but off-hour patrons could still shoot pool with Levi, the designated house-bouncer who lived on the back alley. Or they could attempt to decode the aphorisms of country-bred Cecil on his way out the door to empty the ice container, or peer through the bar and into the kitchen at the rotating cast of immigrant women cooks heating our tater tots and grilling our blue-grass beef burgers with pithy names like “the Griff.”

Holdout patrons from the decidedly more downscale previous owners still visited during those early years, though the EMT’s began appearing less to revive the barflies and breakfast hours ceased. I spent many days hunched and huffing late-afternoon two-for-one High Lifes while, behind me, the same white old pimp from the old days sat in the bar’s first spring-less booth, sipping bottomless cups of coffee while awaiting any calls to come through on the public pay phone then still in operation. On Sundays, when Budweisers were cheap, the same group of Hispanic construction workers still dusted the place, and on those many no-charge nights when the Maracas or the Swells took center stage, post-college hipsters still shook their late-night asses on the dance floor with a few of the neighborhood’s street hookers and the occasional just-freed felon dropped off by yellow taxi-cab.

The mix couldn’t last, and of course it didn’t. As a business venture, Al’s was an anchor institution for we immigrant outsiders venturing upon the city’s disinvested northside, a way to make, as one of the owners would say, the neighborhood safe by resting control of its corner bar. No surprise that the earliest blocks of northside residential gentrification—the initial cost spikes and demographic turnover along Johnson Avenue, Silver Maple, MLK, Rand, Elm Tree, Alabama—all clustered around the energy and relative safety that the bar provided us.

Al’s was our Fort Boonesboro, Fess Parker-style. From it, we blustered forth and staked our claims, belting jubilant songs along the way.

Talking gentrification

By now, this recent bit of local northside history seems no longer controversial, nostalgic even. Its particulars, however, are rarely spoken in polite company. Mostly, the details have gotten yadda–yadda–yadda’d over by the very same polite people who spent much of the past decade aggressively explaining these radiating development spikes in universally positive terms.

This is by design. Gentrification, according to the new whatevs accounts, is mainly something that just happened to Lexington…a bland, agentless, placeless washing over of the landscape. Sort of like smog. Displacement smog. Fixable by intentional tweaks.

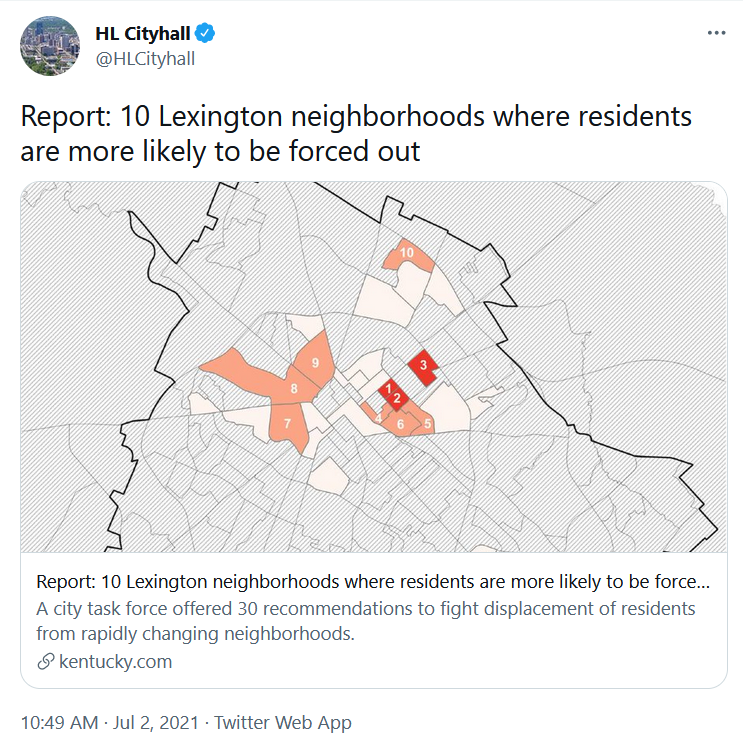

The release last week of the final report by the LFUC Task Force on Neighborhoods in Transition (Gentrification) was only the most recent example of this smog-thinking. Three years in the making and guided in part by highly credentialed members of the UK Geography program and those ubiquitous do-gooders at CivicLex, the NiT(G) report lacks even a single Lexington “case study” of a gentrified neighborhood. Instead, the report relies upon a curated collection of already-existing data to make its claims about which neighborhoods are at greatest risk for gentrification.

The flabby NiT(G) report joins last year’s equally disappointing work produced by the LFUC Commission on Race and Justice subcommittee on Housing and Gentrification. Put together in the wake of the George Floyd/Breonna Taylor protests, that subcommittee was largely staffed by NiT(G)ers, but with a more attentive community audience and a different UK Geographer on board to provide expert guidance.

The Housing and Gentrification subcommittee at least provided a case study: a close look at the Main Street Baptist Church’s dispute with the city over a small part of its $300 million Rupp Arena and Convention Center expansion. The group’s choice was curious to say the least, choosing to magnify a truly exceptional native form of gentrification: not resident or business displacement, but rather the displacement of….250 surface parking spaces for a black church’s 300 congregants.

One day, I’ll take a closer look at those two flabby reports and the people involved in making them.

It seems more immediately important, though, to begin to provide what those expert- and community leader-produced documents strikingly lacked: case studies of actual Lexington gentrification.

A taxing history of the Al’s Bar corner

As in other cities, for a long time Lexington leaders resisted understanding northside development as “gentrification.” Property tax assessments played a key role in that resistance. In our leaders’ early understanding of it, gentrification was mainly driven by a sharp increase in property taxes, which then forced low-income homeowners to move.

This tax-assessment definition of gentrification was akin to understanding basketball chiefly through the lens of the bounce pass, and it unsurprisingly produced some important blind spots. For one, the northside is overwhelmingly comprised of property renters, not property owners.

This definition also placed a lot of power into the hands of the LFUC Property Value Administrator, an elected position held since 2009 by the Democrat and former horse industry employee David O’Neill. During O’Neill’s nearly dozen years in office, the PVA has mostly refused to re-assess any property on the northside. (Editor’s Note: Property assessments traditionally occur every 3 or 4 years.)

On the one hand, this has ensured that no East End Grannies have been at risk of losing their home to property taxes.

On the other, low assessments provided useful data points for characterizing the area’s new Hood developments as exciting and harmless “revitalization.” So long as it was only new homeowners—those choosing to buy homes for three and four times what they sold for pre-Al’s— who were the ones to receive the increased property assessments, city leaders could claim no gentrification was taking place.

In practice, this unofficial assessment lock-down has a negligible tax effect on humble East End Granny’s $40-70,000 home assessment. It provides better advantages to people like me who are buying those homes at their discount assessed value and then investing another $30-200,000 into updating them.

Its best advantages, though, accrue to the largest of early pioneer developers. Which is what makes a taxing history of the Al’s Bar corner an important case study for understanding gentrification in Lexington.

The Al’s corner began its flip in 2006 when a group of family and friends operating under the Bluegrass Meats LLC purchased the bar. Its transformation was largely completed by 2012, when another developer, Chad Needham, completed renovations on two more of the block’s corners. Until the relatively recent opening up of the Limestone and Louden Avenue area, it was the talk of the town for nearly a decade, the home of northside revitalization.

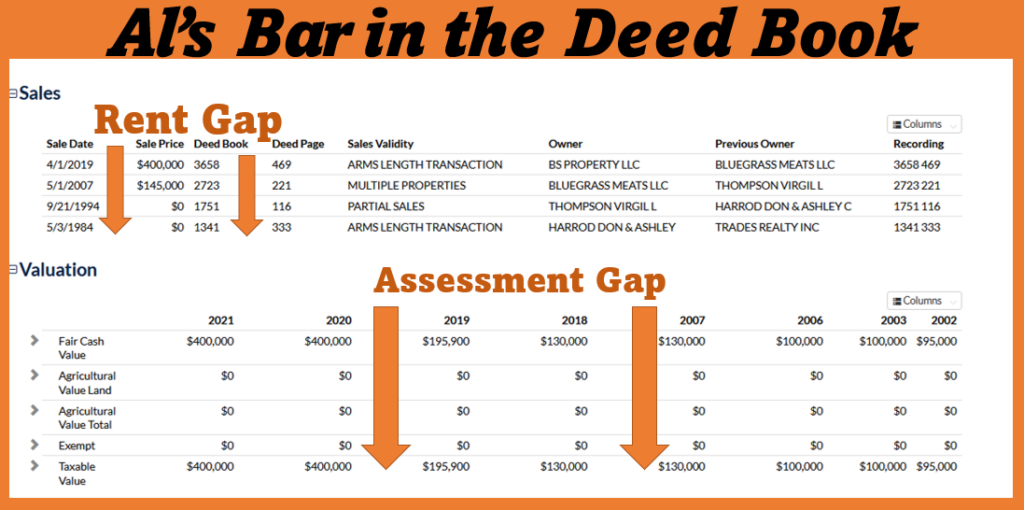

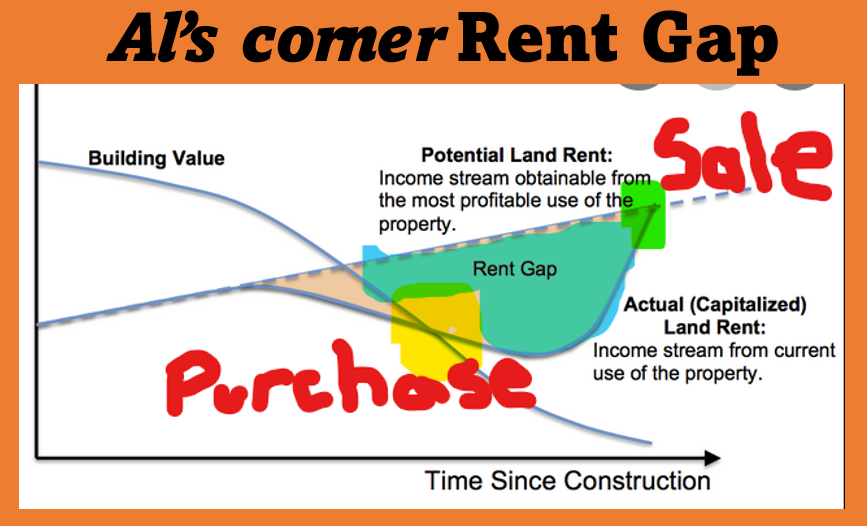

By happenstance, these same two owners have either recently sold (Bluegrass Meats) or are in the process of selling (Needham) some of their Al’s Bar corner properties. Collectively, these sales will allow us the ability to compare the difference between the developers’ pre-gentrification purchase price and their post-gentrification selling price a decade later, producing a loose approximation of the corner’s rent gap.

This rent gap can then be correlated to the assessed values given to the Al’s corner properties by the city’s Property Value Administrator, producing a sort of assessment gap.

Future posts will show how, as blocks around the Al’s corner began to flip with a new upscale class of homeowners and renters looking to patronize these new neighborhood businesses, early gentrification pioneers like the owners of Al’s corner continued to pay taxes as if their lots were part of the same disinvested old-school Hood corner that they had purchased on the cheap a decade earlier.

How much of an advantage were these community leaders getting? I’ll take a look at that in the next installment of this taxing history of the Al’s Bar corner.

Denise Brown

Sorry—spellcheck ‘corrected’ your name, Billie!

Billie Mallory

Hmm, the HL article cites “10 Neighborhoods at risk” which is inaccurate on all accounts. The accompanying maps identified 10 census tracts that actually represent only 4 neighborhoods-East End, Winburn, Westside/G’town St and Cardinal Valley/Alexandria Dr. All have already been gentrified with current homeowners barely holding on to their homes and many vacant properties being held by investors/ developers and the violent crime so high that they are not preferred areas to live in. What was once ‘affordable’ will je no longer when current properties are renovated and rents raised to market rate, property sales values have already doubled at least. What is considered ‘affordable housing’ is not affordable for low and fixed income families. In the time that NIT sat around the table to talk, app 250 properties sold in EE, with 200 properties ‘flipped’ in 2 yrs prior to that, so this neighborhood was already transitioning and ‘passed over’ in its wake (with this data being shared with this group as it met).

Denise Brown

Billy, U are so right, on all points! 🙁