Kenn Minter’s newest comic landscape

By Evan Barker

The Emerald Yeti is an arresting character. Massive in build and dashing in his Army dress uniform, he dominates the frames of his story with gravity. And yet he’s graceful—bold green fur blurring his humanoid features, meshing strangely with twentieth-century surroundings. The Emerald Yeti is a superhero, or he isn’t. Actually, he is, but this aspect of his life isn’t prominently on display in the first two issues of Tales of the Emerald Yeti, the comic which details the background of an oddly named and compelling character.

The Yeti, Incredo-Lad, Incredo-Lass, Professor Hundscheiße, Super-Ego, and Little Miss Fantastic form the phantasmagoric core lineup of creator Kenn Minter and penciler Clarence Pruitt’s comic universe, slyly twisted and irony-laden—a throwback-cum-update to what the authors term “the Bronze Age comics of the rocking, exploitative days of the 1970s.”

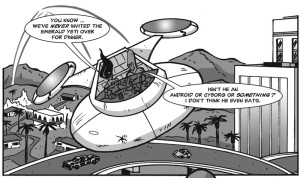

The Yeti first appeared as a member of the Experts, Minter and Pruitt’s thoroughly modern, thoroughly American superhero group. The Experts (graphic novel) is set in the present, a riff on the archetypical cooperative of superheroes. Except the Experts are more about sweet corporate endorsements than actual crime-fighting, much the way celebrity chefs these days tend to sell their images, cookware, books, and utensils instead of making actual food. The Experts collect royalties and bust the occasional hoodlum, and life is sweet. They eventually break up, and that’s where Minter decided that the Emerald Yeti was the most interesting and nuanced character of the group, and the one whose background was the least explored.

In Tales, the Yeti strides into his own backstory in 1972—just returned from Vietnam, walking through the urban blight of a New York-ish American city—and lands in a seedy flophouse hotel, planning to end his life. This scene, like the rest of the comic, is sumptuously detailed and rendered in a historical-feeling black and white. A famous American cultural figure cameos in the background, cracking an off-color joke.

Minter says he “first sketched the Yeti years ago, but I didn’t know who he was or what to do with him at first.” The original inspiration for a super-heroic, questionably jolly, giant green man was actually “this dog toy someone gave me.” It was man-shaped, covered in bright green fur, and Minter immediately mused on what kind of superhero he (the Yeti) could be as “just a big, green, fuzzy guy.”

Stereotypical “BIFF! POW!” fight scenes are pretty much absent in early episodes. He says “I rarely write a fight scene” because what’s most important is “what makes the characters tick.” The lack of fight scenes doesn’t hamper the comic at all, however, because the Yeti’s inner (and outer, we see) conflicts are plenty of grist for a slow-revealing plot. It’s as if we need to see him untangle his personal demons before he can kick criminal ass. This is by design; “all of my characters are messed up somehow,” Minter says. “I’m not interested in creating characters who aren’t anyone.”

The comic landscape

This is to say that Minter tries to differentiate his work from the more mainstream Marvel and DC comics. He points out that they became most interesting in the sixties, after the nanny-state witch hunts of the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. The committee held so-called “comic book hearings” in 1954, parading junk science (specifically the famed Seduction of the Innocent by Fredric Wertham) to prove that the crime comics published by Educational Comics (EC) were a direct cause of juvenile delinquency. [Editorial interpolation: one wonders if the young Tipper Gore caught these hearings on C-SPAN and used them to launch her own dirty music witch hunt decades later].

In reaction, the comics industry self-censored, banning words like “horror” and “terror” from titles. (Minter and Pruitt nod to the olden days by placing the Comics Code Authority logo on the covers of each episode, though a few of the covers pay homage to the scandalous EC illustrations of yore). In the wake of these events, Marvel and DC Comics rose to the forefront and took a different tack, creating longer storylines that explored the actual characters as, well, characters.

The comic landscape has become tough in recent years, declining from its heyday as a massively popular five-and-dime industry offering something for every reader, to its present state, catering to the longtime reader diehards. 1992 saw “The Death of Superman,” and 2007 brought “The Death of Captain America.” Minter dismisses such character-death brinksmanship as cheap commercialism.

“All those superheroes have been killed,” he says, ticking them off. “Batman, Spider-Man, Captain America…they never stay dead. It gets a ton of press, but it doesn’t get people who’ve never read comics into the stores to buy the issue.”

Tales draws inspiration from more recent offerings, such as the works of Alan Moore. In these harder-edged graphic novels, the superhero landscape has gained in plot and moral complexity what it lost in readership, leaving us with (slightly fewer) devoted fans of postmodern, multi-hued heroes and heroines. Tales of the Emerald Yeti fits into this aesthetic. After decades of spandex-clad über-menschen and über-frauen kicking ass with onomatopoeia bubbles, Minter’s work pre-empts the usual all-in-a-day’s-work crime-fighting with real consideration of his heroes as tragic characters (except, you know, green non-snowmen). Like Moore’s Watchmen and V (from V for Vendetta), they are all tragic in some way, he maintains, even the hilariously self-involved Super-Ego and Little Miss Fantastic, in between their episodes of what the kids now call “first world problems.”

The Yeti universe

The yeti (in your general lowercase sense) is also known in other cultural circles as the Abominable Snowman, and this play on etymology informs the character. The Emerald Yeti is both man and not man. He is abominable in ways both supernatural and concrete—the passing hippie calls him a “baby killer” because of his Army dress uniform, and meanwhile the Yeti himself abhors his own appearance and past. “You bet yer pathetic, privileged, little, civilian life mistakes were made!” —he jabs his furry index-paw into the kid’s face. One episode from the first issue provides a flashback to the yeti’s pre-heroic days, scared witless in the Vietnam jungle, very much an ordinary young GI, pondering his family legacy and his responsibility to be the only worthy scion of his line. His aspirations to heroism are dashed, not by Victor Charlie, but by a freak-sneak-attack by unlikely opponents. When he awakens in a field hospital, pruned of a few extremities, the scene is set for the rise of the Emerald Yeti.

The other characters, positioned as ancillaries to the Yeti at first, provide counterbalance and comic relief. As the Yeti makes his way into his new urban jungle home, Incredo-Lad is fresh on campus at Top University, looking the clean-cut yin to the Yeti’s lower-class yang. The hippie girls are gorgeous and curvaceous, the jock dudes still throw Frisbees on the quad, and guitars abound. (The setting is ideal for Minter, who is a fan of the culture of the times, though he is not himself of them). Incredo-Lass drops in, rocking some Wonder Woman style, but with a heavier dose of sexy danger. We later find out that they’re hitting it, in a scene that hearkens to Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft in The Graduate, which must have been a blast to compose. Also, they may be cousins, but that’s left a little grey.

Professor Hundscheiße is a geriatric, lab-coated, campus bench-sitter. He’s got a little of the vibe of the avaricious Nazi archaeologists from Indiana Jones, if they were chick-ogling pervs with a poetic bent. He’s fixated on some mysterious university property–a component of something being delivered soon, but we don’t know what it is. Minter does. He chuckles at the observation that it tantalizes like Marcellus Wallace’s briefcase from Pulp Fiction.

Still, the above observations are the reader-response critique of one reviewer (a graphic novel non-native, to boot), and should only be taken as teasers for the real thing. Minter has thoughtfully shared a readable copy of these two volumes on his website, and downloads are available for purchase there. Readers may look forward to The Emerald Yeti appearing in print, and new pages of the story appear frequently on the site.

For all that’s packed into these two issues, the Yeti and friends could wind up doing literally anything. Why is the Yeti a yeti? Are Incredo-Lad and Lass actually cousins, and does that mean they have to stop boning? What’s that component that Professor Hundscheiße covets? Will Super-Ego and Little Miss Fantastic get anyone to come back to their house for dinner?

To be continued…

Kenn MInter/Emerald Yeti information: On the web at notfromherecomic.blogspot.com. These local stores carry Minter books: Wild Fig, Collectibles, etc. (Richmond Road), and Morris Book Shop.

Leave a Reply