Editor’s note: This is part three of an inquiry into the Lexington Committee on Housing and Gentrification’s need for authentic community voice . You can read part one here: Story mining the Hood, and part two here: Civic Mining, the early years.

While earlier Lexington eras of progressive civic outreach ignored or paid lip service to everyday citizens, our current era is notable for its developed need to document the community voice. This trend has led to the political rise of a host of story catchers, people and organizations whose job it is to collect, document, categorize and organize individual stories into a set of actionable civic items that represent the voice of a community.

Most story-catchers are paid for their services by a government entity or some outside foundation. And while they exist across a broad range of city neighborhoods, our local story-catchers mostly operate in the areas surrounding downtown Lexington and a few low-income neighborhoods scattered throughout the city.

Story-catchers represent a diversity of job types. Urban planners like Stan Harvey of Lord Aeck Sargent, lead story-catcher for the Rupp Arena Arts and Entertainment District and a host of other civic Hood studies, are generally highly-trained specialists with degrees in fields like architecture, urban studies, regional planning, and landscape design.

A next level of story-catchers derive from the non-profit fields, often non-expert college graduates who present themselves as community or neighborhood activists.

Finally, a third level, represented by your city Task Forces, Commissions, On the Tables, and the like, mushes together urban planners and non-profiteers, adding to this mash a series of job-specific experts like home-owner association presidents, university faculty and administrators, school leaders, and elected local representatives.

All wield inordinate influence as gatekeepers between the Community and the Establishment and thus deserve a little more scrutiny as a connected class with a history of specific civic interests and operating procedures.

The East End Small Area template

In Lexington, we might finger 2007 as a formative moment in the rise of the story-catchers. This is when the city and its affiliated partners began work on the East End Small Area Plan,

Intentionally designed as a community document, the East End Small Area Plan aimed to guide the neighborhood’s transition away from its history as home of Bluegrass-Aspendale, a former housing project created (via progressive civic oversight) in the late 1930s as a 350 unit low-income housing block for black folk, and expanded (also through progressive civic oversight) over the next four decades into a 900-unit complex of entrenched bi-racial poverty.

In part due to changing national trends in what was considered acceptable affordable housing stock, Bluegrass-Aspendale had begun decommissioning its housing stock in the 1990s. By the early 2000s, the projects had been completely dismantled and, as with earlier eras of civic slum clearance, most of its residents scattered throughout the city and region.

This bulldozed center of the East End neighborhood then received a federal Hope VI grant (still more oversight) to rebuild the area as townhomes, apartments, and suburban-style ranch-homes to a human density roughly half that of Bluegrass-Aspendale. The new Hope VI neighborhood, eventually renamed as Equestrian Estates in a nod to the city’s deep love of horses, would sit at the geographic center of the city’s East End Small Area Plan.

Community engagement was crucial to the East End Small Area Plan. Here is how EHI Consultants, the urban planning company charged by the city to engage the community to develop the East End plan, describes that process on their website:

EHI was involved with facilitating extensive public involvement of neighborhood residents and stakeholders. This process was largely successful with more than 150 individuals turning out for the kick-off rally and 75 for the initial visioning session as well as favorable articles in the Lexington Herald-Leader newspaper and by downtown associations.

In addition to public involvement, the plan encompasses the examination of economic opportunities, diversity issues, infill development; mixed land use, open public space development, social capital and neighborhood character development.

EHI Consultants

The resulting report is wonderfully put together, mixing maps of housing, zoning, income, code violations, and other data with explicit community intentions for what to do with it. The report lists thirteen goals, and covers forty pages explaining these goals, bench-marking them, and then placing them within an intentional ordering system of short, mid, and long-range projects.

Community voice was so central to the plan that, four years after EHI’s East End plan was completed, 2013, a new civic group was started by former East End councilmember Andrea James . This group, which was housed under the non-profit umbrella group Bluegrass Community Foundation, initiated a follow-up set of community voice-sessions. From North of Center’s coverage of these community talks:

The time has come to re-evaluate the progress of the East End Small Area Plan and its thirteen goals. To that end, former District 1 Council Member Andrea James has organized a series of monthly open meetings designed to re-engage the East End community and address progress and obstacles to the plan’s priorities.”

“Updates on the east end,” Feb 2013

This focus on hearing from the East End community seemed to obscure a larger point, one most likely understood by some in the community but not ever registered directly by the story-catchers.

The big community concern in 2007, and also in 2013, was that mainly white developers like Phil Holoubek (one-time Board Member of East End property owner Community Ventures CDC) and former Vice Mayor Mike “the Bulldog” Scanlon were going to be the ones to benefit most from all that clear Hood voice for more economic development and better living conditions.

They were also concerned that not only might connected wealthy developers like these be granted over $10 million in city and state TIF subsidies to redevelop the Third Street commercial district of the East End, but that the city’s other East End investments—park upgrades, the Town Branch Commons Trail—might generally be put on hold for years until completion of these much larger subsidized projects.

We can see these concerns more clearly now in 2020, as a second layer of developers have now asserted themselves, investors who for a decade have been busy buying and developing property to rent out to mostly white-owned outside businesses. That you can see this second layer take off, smaller in scale yet still inordinately wealthy for the area, is why the city’s been forced to have all these sorta-not-sorta civic task forces on gentrification.

Not to get all poetic, but…

But because you

did not see it

does not mean

it was not

seen.

For those skilled at reading between the lines of the city’s story-catchers, this was apparent in 2013, too. From a North of Center report on the second community meeting of Bluegrass Community Foundation representative Andrea James’ update to the 2009 LFUCG East End Small Area Plan:

The meeting was momentarily disrupted when an African-American man burst into the room ranting about where the “real” community was. Even though this series of meetings is free and open to the public, and a multi-media invitation has been sent out to all citizens who would like to get involved, he insisted that residents in the East End were not given an equal opportunity to contribute.

“He doesn’t think any of us actually live here,” said [Sherry] Maddock, shaking her head as facilitator Andrea James firmly requested that he either contribute productively to the meeting or leave. Apparently the man is well-known for popping up and creating these kinds of disruptions. Despite the cultural diversity of the participants in the room, it was a reminder that the histories of racial and economic tensions unique to the East End, both real and imagined, definitely impact this process.

“Accomplishments, delays and absentee owners,” March 2013

Let me paraphrase this 2013 East End scene for you: two white women (the journalist and the neighborhood association vice president) and one black woman (the facilitator/former councilmember) told an unnamed black man demanding better community representation….that he was out of order and a known crackpot who ranted about an “imagined” racial and economic tension.

And then these three women–and the LFUCG Planning Director and Bluegrass Community Foundation CEO and other community stakeholders in audience that night at the community meeting–

moved on

without him

because they

were being

black and white

together

in this process.

Rise of the story-catchers

By 2013, when former CM Andrea James began tapping East End residents for their Hood stories of progress and challenge, a number of Lexington non-profits had set up shop on the northside. Though nearly exclusively comprised of newly arriving gentrifiers with a limited community skill set but a vastly superior access to civic and private capital, these groups began getting into the low-income community voice game.

Remember the NoLi CDC Cultural Plan for equitable art? It relied on data “gathered by the UK Community Innovation Lab as a part of the work on [the grant-funded NoLi Night] Market, through 2 gatherings (one each at the Plantory and Embrace Church) led by 10 Community Researchers who were hired to act as liaisons to the community in this process…to get input from individuals in the neighborhood who were invited.”

Or how about the Foodchain-directed “Smithtown Kitchen Store Report” from 2015, which interviewed low-income youths in the gentrifying Jefferson Street corridor to discover that, yes, there was “a strong demand for a grocery that can provide healthy, fresh, affordable food to this neighborhood, where there are no other options” (except for a craft brewery owned by the husband of the FoodChain CEO, and later an upscale barbecue joint and on-brewery fish-monger who both paid rent to said husband).

No? Maybe you missed it while participating in the National Main Street Center program, also from 2015. That one surveyed community residents to find out how to revitalize the North Limestone and East End corridors. The community data mining produced through these sessions were brought to you through a partnership of NoLi CDC, Bluegrass Community Foundation, Lexington Downtown Development Authority, and the John S. and James Knight Foundation.

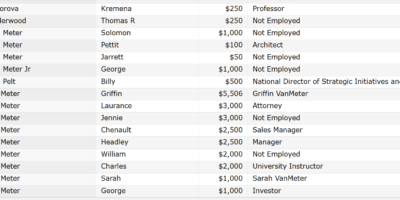

Maybe you recall the citywide non-profit hub The Plantory, and its bold first stab at recognizing gentrification: the Neighborhood Arts Project! That one took a grant from the city-funded LexArts to collect stories from residents at risk for removal by gentrification so as to create a mixed-media art project.

That project was a success: it debuted during the May 2017 Gallery Hop at the West Sixth Brewery-adjacent Plantory Lounge. It was so successful, in fact, that it instituted a follow-up project on code violations that promised to help show Hood residents, ages 10-and-up, “how to take data and create it into art!”

Pre-Covid, if you felt like the last decade was a gentle, only slightly tiring, upslope of Lexington progress, a city of happy and determined people who have had their voice heard and “listened to” by some gosh-darn good people, it’s probably because you were relying on the journalists and community leaders who were ingesting and circulating all this crap. To you, all these commissions must seem as strange as the Covid shutdown itself.

Apparently, there are a lot of these gentle up-slopers in our leadership circles. How else to explain why many of the story-catching gatekeepers of yesteryear seem to hold the powerful gatekeeping positions in the commissions of today. Can we honestly put any faith in these people: can they understand our city well enough to shift it sufficiently away from the old world they had been claiming we all wanted to work towards?

What else but poor listening skills can we attribute to this new 2020 cohort of commissioned civic sub-committees, leaders who must listen to even more of these painful, time-consuming, unpaid community testimonies? Is this deaf ignorance, or are our gate-keepers just a roving collection of community sadists?

Billie Mallory

It has been a wild ride indeed over the past decade. Having been involved in East End and Central Sector Small Ares Plans there was considerable resident involvement along with community partners. Both plans called for a community development corp to ‘drive the plan’ but no funds, nor technical support was provided to make that happen. However, both communities formed a grassroots organization to drive each plan separately and differently. NoLi CDC was largely professionals that became developers of choice to redevelop York St and part of N Lime corridor. EECDC created a board of residents/advisors that has worked with developers and business owners, promoted home ownership and empowered residents to become more proactive in decisions about their neighborhood. Many of the goals/objectives of both plans have been accomplished but there is still on-going advocacy and work to be continued to lessen the impact of gentrification.