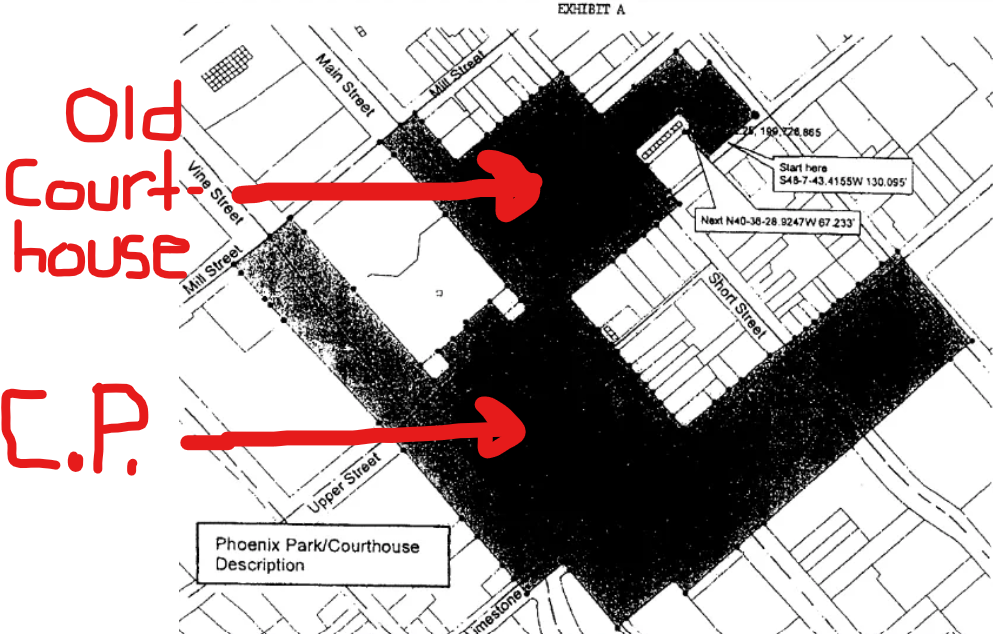

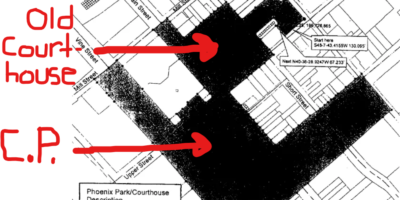

A reflection on my visit to the DAP celebration held in the Limestone Hall at the renovated Old Courthouse, which sits inside the northern edge of the CentrePointe Tax Increment Financing zone.

This is Part 4 of my ongoing reporting of the CentrePointe Tax Increment Financing development project, which developed out of a series of FOI requests. Articles in this series include:

Part 1: The CentrePointe TIF matures

Part 2: How TIFs work

Part 3: The Project and the Zone

***

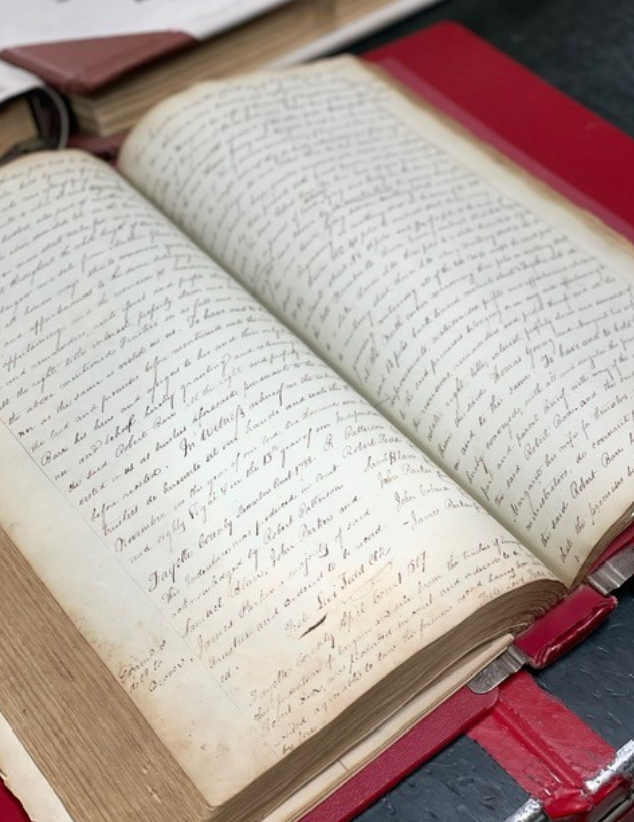

One night last November, I headed down to the Old Lexington Courthouse for a public celebration of the Digital Access Project (DAP). DAP aims to digitize and then transcribe all Fayette County property records, which date to the county’s eighteenth century founding. I had been invited to attend the celebration after spending a full season of Wednesday afternoons in volunteer support of the project, hunched over a scanner at the Fayette County Clerk Office and negotiating 200 year old deed books.

I didn’t stay terribly long. I arrived to the Courthouse late but heard most of the speeches. Afterwards, I waited in line to give a quick hug to Shea, the event’s featured speaker who was the point person for my work at the Courthouse, and then exchanged numbers with Chris, the UK grad student with whom I had volunteered my Wednesdays, and got to meet his wife and their newborn. I’m sure I grabbed a snack for the walk home and a print brochure explainer of the scanned county property records to read later.

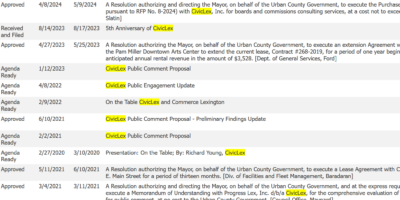

I did not think much more about the night until recently, as I have been combing through tax increment financing (TIF) documents related to the CentrePointe (now City Center) project. These documents show that the Old Courthouse, along with several other nearby urban lots, reside inside the CentrePointe TIF zone.

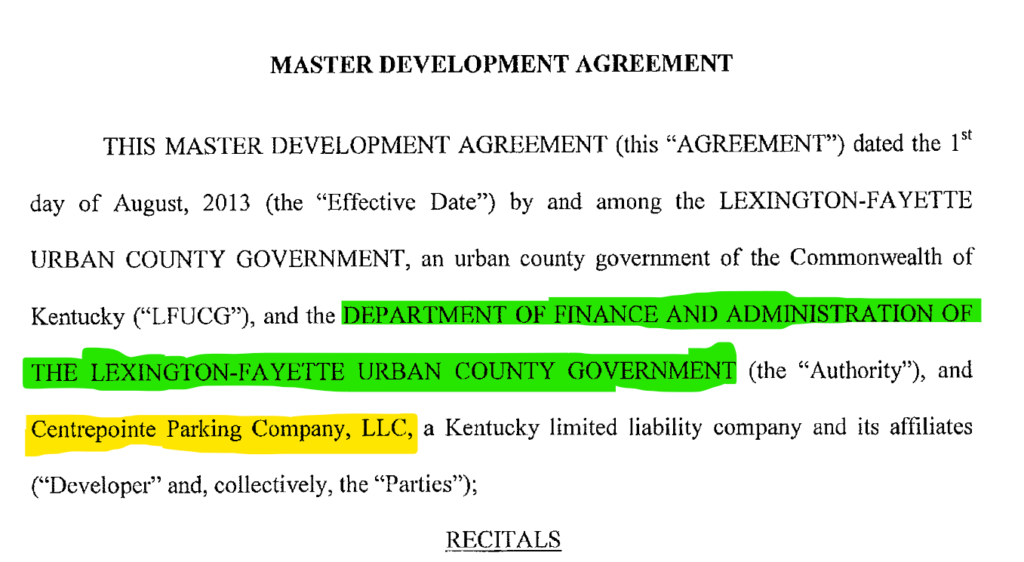

As such, 80% of local taxes generated at the publicly-renovated Old Courthouse (likely more, as I note here) are deposited instead into the account of Centrepointe Parking Company, LLC, a subsidiary of the Webb Development Company.

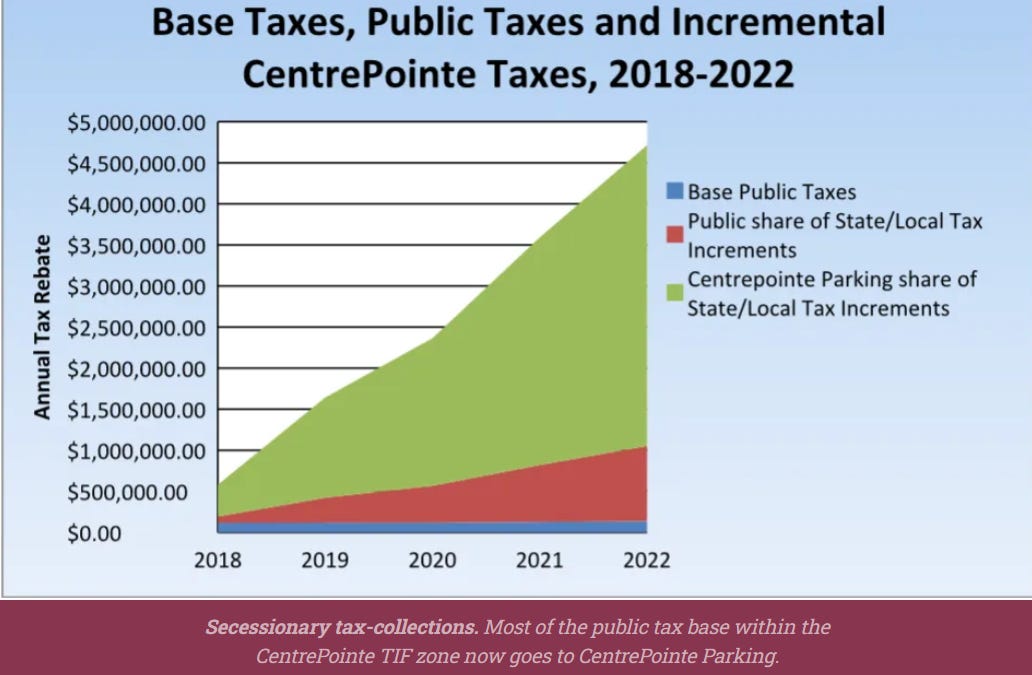

The Freedom of Information documents I received on the project do not detail the precise amount in Old Courthouse taxes that have gone to CenterPointe Parking Company, LLC, over the years. But for the entire CentrePointe TIF zone, these numbers are quite high and increasing annually. Over $3 million in local and state taxes in 2022 alone.

The 2023 check that the city will soon cut to CentrePointe Parking Company, LLC, will likely include the taxes paid for the on-site services involved in staging the DAP celebration that I had briefly attended. Rental of the top floor of Limestone Hall. Catering. Staffing. The levy for a night of civic celebration, of recognizing the selfless work of community volunteers and the promising achievement of higher ed and local government bureaucracies coming together to work on a low-cost, high impact project. Nearly all of it accruing to CentrePointe Parking Company, LLC.

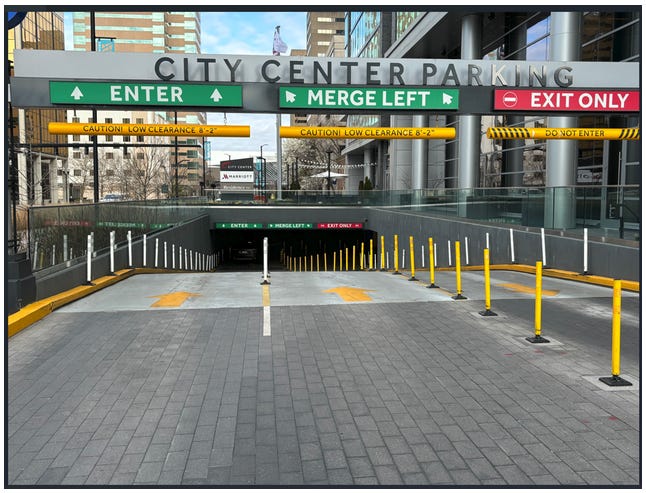

In theory, the night’s taxes went to the parking services company because all of the Old Courhouse patrons, including DAP celebrants but also those customers I passed on the first floor who were sitting at Thirsty Fox or Zim’s Restaurant, had parked in the company’s 3-story underground parking garage. This, the 3-story privately owned underground parking garage, is the object of “public infrastructure” that the CP TIF contract pays toward.

This contractual explanation would be odd if it were true. There are two parking garages located closer to the Old Courthouse—each by a city block—than the Vine Street-facing CentrePointe one. Even more convenient than parking garages for Old Courthouse consumers, on-street parking surrounds the building and extends a full block in nearly all directions. There are even surface lots.

And of course, some people in a city just bike or walk to after-hours events. I did. But so it goes with TIFs, which in addition to being pompous constructs, are also illogical.

Fayette’s large landowners, then and now

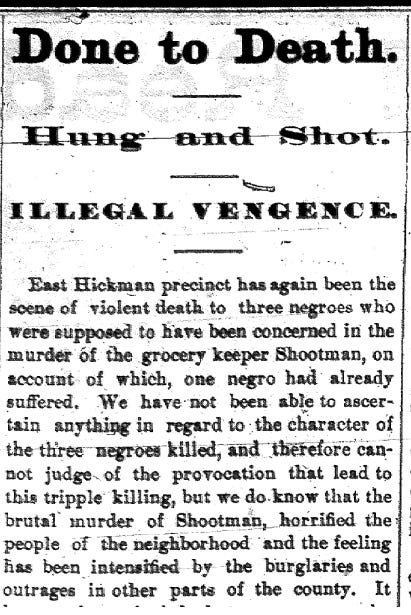

But there is something more troubling. I came to my DAP volunteer work by way of a research question. Since 2018, I have been researching a series of four lynchings that occurred across the winter of 1877/78 in Fayette County’s East Hickman community. In many ways, the lynchings officially ended the era of Reconstruction in Fayette County and announced the brutal onset of Jim Crow America. You can see the first two videos here and here, which focus on the lynching of Fayette resident Tom Turner.

Before turning my attention to the next man caught up in that winter’s mob violence, I wanted to know: had any of the lynched men showed up in slave records from the decades before, when slavery was still legal? If so, which Fayette County families had claimed contractual ownership?

I contacted DAP leaders because their project was specifically oriented around using the digitization of all county records as a means to identify and locate slave names and families.

Because slaves were considered chattel (moveable goods; capital), property deeds are the one consistent place where traces of their lives appear in the written historical record. Reflecting this focus on transmitting slave records for modern consumption, DAP labor and project funding came primarily through UK’s Commonwealth Institute for Black Studies (CIBS) and the Black Prosperity Initiative, a fund of anonymous donors housed at the Bluegrass Community Foundation.

Most likely, the night’s sponsor was CIBS, a relatively new interdisciplinary academic department which in 2020 was awarded part of a $10 million “UNited In True racial Equity (UNITE)” grant awarded by UK, seemingly in response to the widespread national protests centered around George Floyd’s filmed suffocation by several police officers. (The Floyd protests also seem to correspond with the creation timeline of the Black Prosperity Initiative.)

In awarding CIBS and other UNITE recipients the money, UK President Eli Capilouto had charged the interdisciplinary group with grounding its scholars’ research in local work. DAP, the project for which I volunteered my labor, was a natural and powerful expression of Capilouto’s charge.

The night of celebration at the Old Courthouse reflected this. Speakers spoke in emotional and analytic terms of how the enslaved were passed down in deed records to white family members. How they were shuttled around the region to satisfy other debts or credit lines. How their bodies were used as capital to secure mortgages for home construction or future land acquisition.

Despite the night’s topic, I doubt any DAP representative gave any thought to the present legal contracts that had gotten us all to gather here, in a building that as a matter of unremarkable course would deliver all its taxes into the checking account of a parking company run by one of Lexington’s largest and most powerful present-day landowners.

Nor should they have. By design, our TIF contracts exist like scraps of paper in a cluttered office, buried but not inaccessible, legible but neither loud nor large, and easily overshadowed by pretty edifices like a newly renovated event space located in a historic building built by a local black architect. In this, TIFs operate much like the frail antebellum paper documents of Fayette’s former plantation owners that I had spent the Fall scanning with Chris.

Of the considerable coverage of the 2018 opening of the Old Courthouse, none mentioned that the newly privatized space would likely be generating tax money for the private developers across the street. The detail, seemingly, was not considered newsworthy to a Lexington audience.**

But the detail does exist, and it will structure the fortunes of families and the development of our downtown for the next 25 years.

A coda of sorts

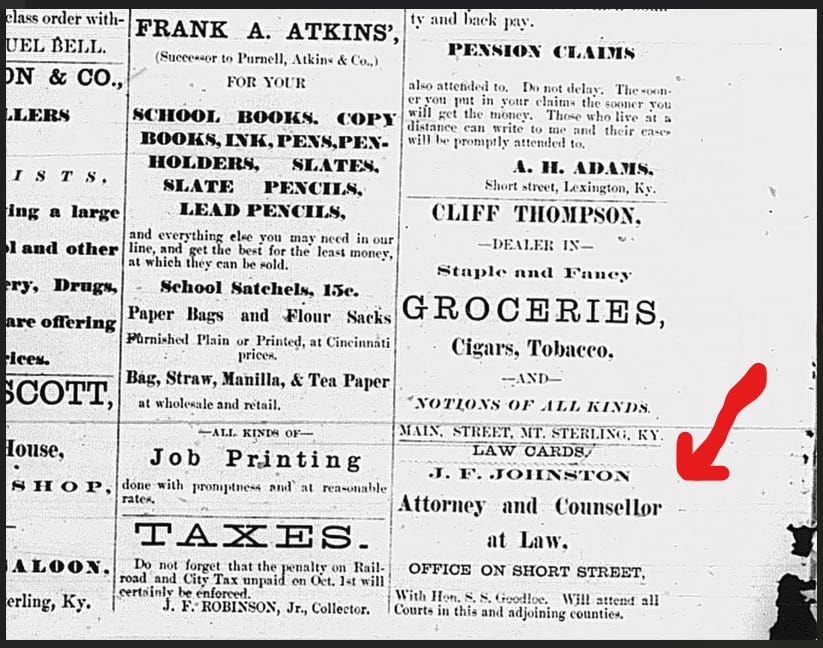

In my research on the 1877/78 East Hickman lynchings, I remember coming across an advertisement that appeared in the American Citizen, a Reconstruction-era black newspaper that circulated in Lexington for several years. The advertisement was from JF Johnston, a white lawyer with a downtown Lexington office.

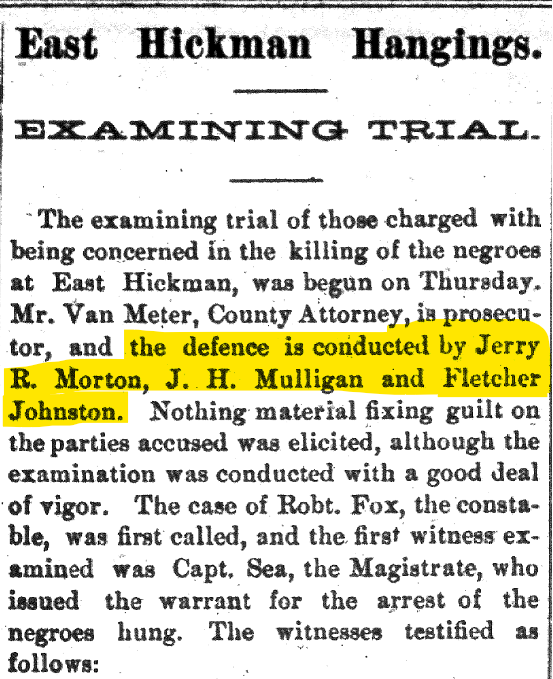

Johnston, it turns out, would also be the lead defense lawyer in the East Hickman lynchings. It was he who successfully defended the five or so white men on trial for various charges related to the East Hickman lynchings.

Johnston was a respected community leader of his day. He did more than lawyer. While defending the accused men in a lynching trial covered by newspapers from as far away as New York City, Johnston was also running announcements in the local white newspapers of his intent to run for County Judge in the Democratic primary of that year.

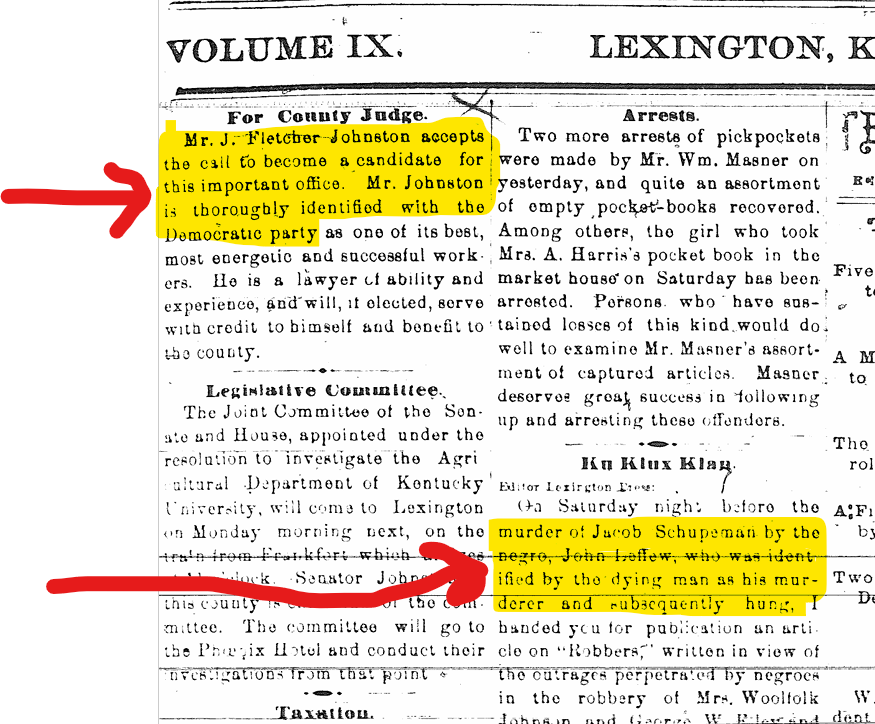

In this image from the January 26, 1878, Lexington Daily Press, here is JF Johnston accepting the nomination to run for County Judge at the top-left. Meanwhile, a column lower, JF Johnston appears again, this time re-circulating an op-ed that he had penned in defense of mob rule. It was originally published in December, a week before the first of the four East Hickman lynchings.***

Johnston’s opponent in the Democrat primary? The very same judge, Judge Stevenson, who would preside over the East Hickman lynching case.

It is not explicitly reported as such in the papers of the day, but Lexington had two community leaders leading a murder trial who were also otherwise engaged in a game of political one-upsmanship. In what appears to have been a sham murder trial, all the accused white men were declared innocent and set free, despite eyewitness testimony from the wife of one of the men (Tom Turner) who was lynched. What Democrat running for office in 1870s Kentucky, after all, would dare find a white man guilty of lynching four black men of the lower class, none of whom appear to have held property or owned a business?

Only a limited number of issues of the American Citizen have been located and preserved. Johnston’s advertisements appear two years before the lynchings and his defense of the East Hickman men. It is of course quite possible that, in a subsequent issue that is (at the moment) lost to time, American Citizen editors addressed Johnston’s choice to represent the accused lynchers, and his decision to run for County Judge as an enthusiastic Democrat.

To my modern eyes, though, the incongruity was jarring. Why would a black newspaper advertise for a wannabe leader of the political party that was actively trying to take away your newly won freedom? One who seems to have sanctioned vigilante violence against you?

I should not have been so naive. Every age has its public customs; all territories their musty hidden contracts. We must all of us move through and navigate both the custom and the contract. Things do move and bend. Chattel slavery begats vigilante justice begats de jure segregation begats de facto segregation begats DAP and CIBS and UNITE and Joe Biden.

But some things remain. The good leaders of the day leading good lives that empower good institutions for the future good of their homeland. Progressive and pragmatic. Farmers maybe. Lawyers probably. Merchants. Wordsmiths. Developers. Evangelists. People willing to bend certain of the day’s codes and to strongly adhere to others.

Who am I to blow against these unremarkable winds, heavy and wet though we of a later age may find them to be?

_____________

I write for SubStack. If you found it worth your while, please share this article as it appeared in SubStack. While there, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber to receive new posts and support my work. Subscription money for my SubStack pays to keep this site running (and also my bills and daughter’s college fund).

**If it was mentioned at all, the CP TIF was presented to readers as a lucky gift that made the Courthouse renovation possible. This was true but not particularly comforting: state lobbyists had written into law an exemption that allowed TIF projects to also be eligible for Kentucky’s Historic Preservation Tax Credits—with very specific stipulations. So…not one tax break, but multiple tax breaks larded onto each other!

Here is the Chevy Chaser (which did the best reporting on the subject) on the stipulations: ”To be eligible for the tax credit program, a project had to cost between $15 million and $30 million, be completed between 2015 and 2017, and be a historic building in a TIF district that hadn’t ever been utilized.” The exemption was written into law for Lexington’s 21C TIF, which was awarded to the private boutique hotel co-owned by current Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg. The law also applied to the Old Courthouse renovation. (Sort of–the project was claimed to cost $32 million, but who am I to blow against that bended wind?)

To sum up Lexington’s coverage of the CentrePointe TIF as it related to the Old Courthouse renovation: We got lucky, Lexington! Because we are already paying taxes going forward to CentrePointe Parking Company, LLC, and because some crony lobbyist wrote a crooked TIF amendment to help some of his crony wealthy clients from Louisville, we now have the great-good fortune to leverage $20 million from our budget to build a few more downtown bar-restaurant concepts!

***It is possible that there are two different JF Johnstons. My research stopped before I could confirm through census or other records.

Leave a Reply