In the previous installments of this series, I discussed two marketing strategies—creating perceived value of a product or service, and encouraging customer retention through loyalty programs—and how institutions such as Bluegrass Community & Technical College are using these strategies to attract and retain “customers.” This is a result of the process of corporatization, through which higher education has come to adopt the business practices of private industry, in an effort to better compete in the “education marketplace.”

Those two articles examined BCTC’s marketing strategies and business model by way of analogy, comparing its efforts to increase revenue and reduce expenses to the tactics used by fast-food restaurants, airlines, and convenience stores. Yet a transaction, such as the exchange of money for college credits, requires two parties, and so far I’ve only discussed the consumption of higher education from the perspective of the sellers. But what about the buyers? Who are BCTC’s customers, both current and potential, and how do they respond to BCTC’s retail-inspired overtures?

As a veteran college instructor, I’m in a position to make some observations about BCTC’s customer base. From 2002 until earlier this year I taught English composition, the last six years at BCTC. Freshman comp is of course a universally required class, and as such we teachers see all types of students there—and we see them before they drop out. And we see that community college students have wildly different needs and motivations, just as retail customers do. Here I’ll consider the ways in which BCTC’s adoption of a retail business model does or does not address the needs of its target consumers.

It’s common for businesses to try to understand their customers by categorizing them into various types. For instance, there are customers loyal to a particular brand: in the previous article in this series I described my father’s habit of buying new Toyotas every couple of years, having been impressed by that brand’s quality. And there are impulsive buyers: recently my uncle, having dropped by the dealership on a whim, traded in his sensible Nissan sedan for a two-door coupe he didn’t really need, or even know he wanted when he woke up that morning.

My uncle could also be categorized as a discount customer, one swayed by a significant price reduction—a bargain hunter. The coupe he drove home was last year’s model, and he got the car at not much more than dealer cost. But he certainly wasn’t a need-based customer; those are people with specific requirements, who know exactly what product they want and where to get it, and don’t to need to shop around. I fit this category myself: after rust rendered my elderly Chevy pickup unsafe to drive at highway speeds, I created a list of my preferred vehicle characteristics, then determined, after hours of web research, which lightly-used vehicle most closely fit my criteria, and which regional dealer could sell it to me for the best price.

Finally, there are wandering customers: those who don’t know what they want, or if they even want anything at all. In our car sales scenario, they’re the customers who are perfectly happy with their current wheels, but just like to see what’s out there. They might even take test drives, but have no intention to buy. For them, wandering a car lot, perhaps on a lunch break or while running Saturday errands, is nothing more than something to do.

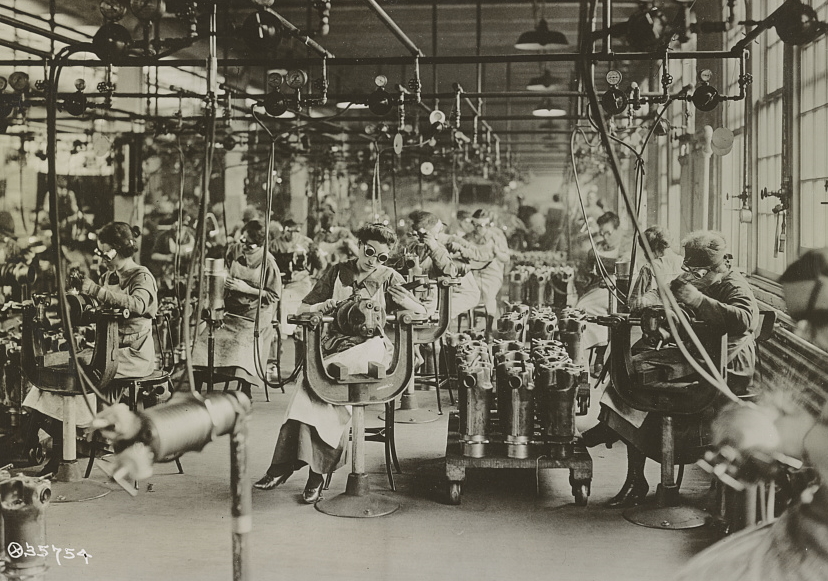

There are correspondences between these categories of car customers and the types of students who enroll at BCTC. First, a substantial number of students arrive in the classroom knowing full well why they’re there, and what they hope to achieve. There are students who enroll in technical programs, such as industrial maintenance or HVAC certification. There are students who plan to matriculate at a four-year college, but lack the financial resources or the academic credentials to make the jump straight from high school. And there are working adults, for whom a college degree opens doors to promotions, pay raises, or a different career entirely.

Students of this type—what the retail industry would term need-based customers—are the core of community college enrollment. And they don’t need much selling to; they already know, with some degree of specificity, what program they aim to complete, and they know where to find it. Presumably what they need most from their college program is quality: competent training for technical occupations, or rigorous instruction across academic disciplines for future transfers. In short, they need the best instruction they can get, and they’ll more than likely keep coming back until they get it.

Some students are less clear on their motivations. As an instructor I’ve noticed that while some working adults are targeting that promotion or career change, others might just be testing the waters, or trying to keep their résumé current with a computer or math class. Still others might take, say, a literature or history class just for the fun of it: education for education’s sake. These students are similar to impulsive or discount customers: they’ll sign up if the mood strikes them, but they’re not going to commit to a full-time program. What these customers want is a sense of satisfaction that their time and money hasn’t been wasted. They’re unlikely to provide much future revenue (in the form of tuition payments, in the case of the business of higher ed) but they’ll certainly recommend a class or professor to their friends if they’re satisfied. Or they won’t, if they aren’t.

Then there are those students who have absolutely no idea why they’re in the classroom in the first place, let alone what classes or programs are best for them. These students are always freshly graduated from high school, or at most a year or two out of it, and they enroll because it’s something to do. Like signing up for 13th grade, in a way. Possibly their parents threatened them with eviction if they didn’t either get a job or go back to school; maybe they saw their friends leave, and enrolled to stave off the loneliness. In any event, just having somewhere to go and something to do on weekdays isn’t nearly enough motivation to succeed in a college program.

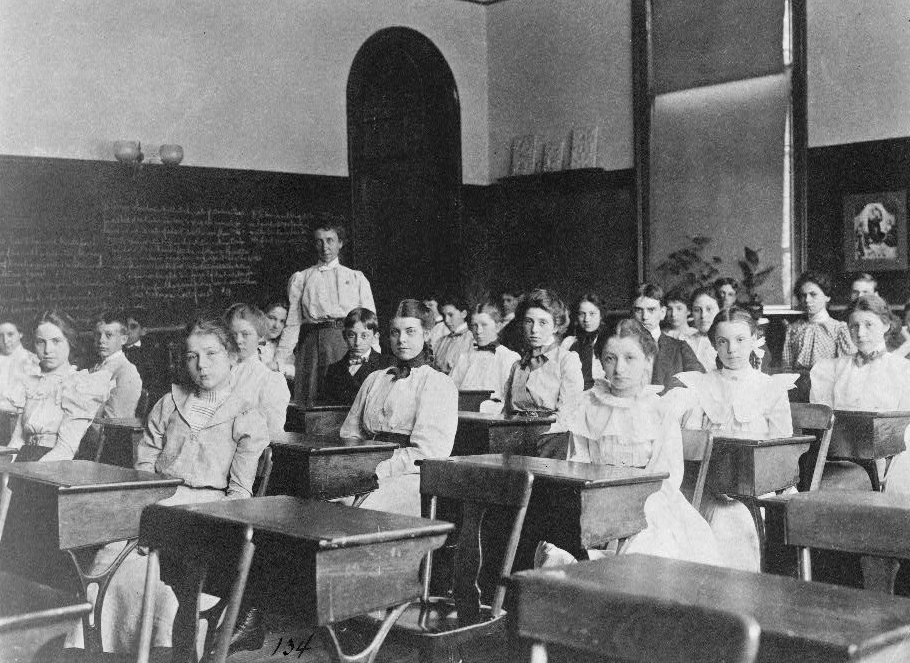

From a teacher’s perspective, these students are the worst: they’re visibly bored, often unresponsive in discussion, don’t try very hard, and probably won’t continue past a semester or two. They’re the wandering customers of higher education; they won’t keep buying, because they haven’t yet bought into the whole idea of the thing, and perhaps never have and never will. There could be many reasons for this, such as parents or guardians who didn’t rate education highly, or pressures from peer groups, or problems with self-confidence, or crappy schools along their K-12 tracks. Whatever the reasons, they’re simply not ready for the demands of college.

And honestly, that’s fine. Students such as these probably shouldn’t be in college, at least not until they find their own reasons for being there. They shouldn’t waste their money, and they certainly shouldn’t take on debt, if that’s what’s required. And they shouldn’t waste their time, nor that of their instructors or classmates. For years we’ve been told that college has become a necessity, that a Bachelor’s is the new high school diploma, but a growing body of evidence suggests otherwise; fewer than half of the fastest-growing occupations in the U.S., for example, require education beyond a diploma and some job-specific training. Likewise, state governments, including Kentucky’s, are now realizing that trade apprenticeships are often a much faster, less costly path to high wages and economic growth.

Despite this evidence, it’s precisely those aimless, wandering customers to whom BCTC seems to be concentrating its marketing efforts. Skimping on faculty salaries and relying on part-time instructors saves money and allows BCTC to advertise itself as a “smart bargain,” and spending what it’s saved on $500 customer loyalty rewards might persuade students to keep enrolling, even when they have no real commitment to their studies. To the latter point, it’s worth noting that in the last few years BCTC has installed an entire course area, called the “First Year Experience,” to try and teach marginal students how to survive college, covering topics such as “college etiquette” and “self-analysis,” in the hope of retaining some greater proportion of them come next semester. Needless to say, students of the first two types, the genuinely motivated and intellectually curious, usually find the class, at best, a waste of time and tuition. Nor can it ever accomplish the task for which it’s intended: making students want higher education. Self-motivation, after all, must come from the self.

Yet this is the retail imperative: get as many customers through the door as possible, and then do everything in your power to keep them coming back. Fair enough, but the strategy by which BCTC seems to be pursuing those goals isn’t by providing the highest quality product it can, but by skimping on faculty salaries and offering frequent-buyer discounts. This sort of strategy, while it may bring in more revenue in the short term, does a disservice to those students who want real value. Time will tell what the long-term effects are.

Leave a Reply