My daughter, the May Day Kid, spent her first three school years, Kindergarten through much of Second Grade, taking the bus to school. Not the school bus. LexTran.

For three years, she and I hopped the #7 line at one of two North Limestone stops between Third and Fifth, rode it across the northern Circle to its outbound terminus at Augusta and Anniston, disembarked, and then merged with the flood of neighborhood kids drifting the final couple hundred yards, past the crossing guards and the drop-off kids idling in the back seats of cars stacked up by the dozens, toward teachers and principal standing to greet us at the front doors of Dixie Elementary School. I dare say that, as she ages, few places in the world will be more anchored in the Kid’s childhood mind than the area surrounding Anniston and Augusta.

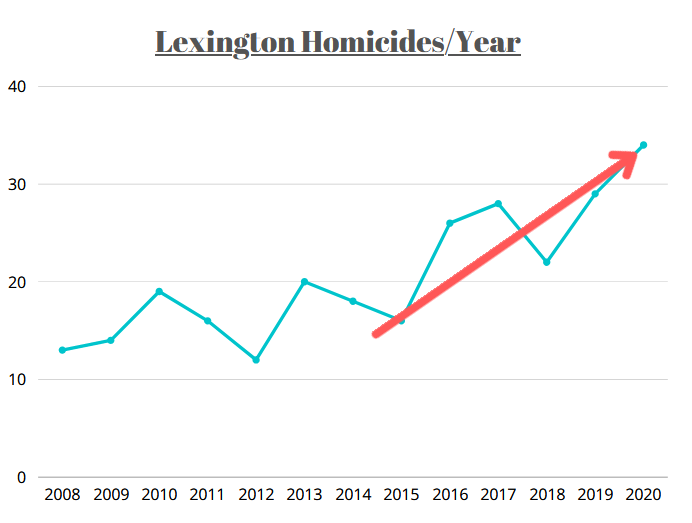

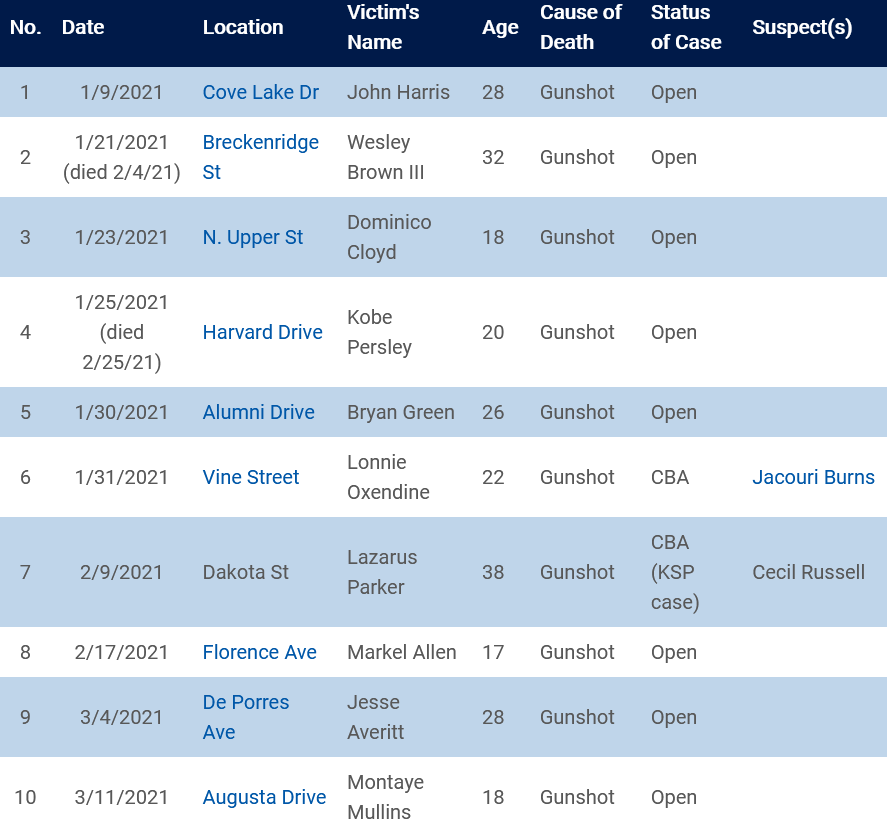

Anniston and Augusta is also a current hot spot for the city’s multi-year increase in homicides. Since 2015, the city’s annual murder rate has nearly doubled, increasing from roughly 15-20 homicides per year to 29 per year. Last year, 2020, broke 2019’s record: 34 homicides.

This year’s tally, currently at 11 with a homicide this week, seems poised to challenge for another record year. Anniston and Augusta has featured prominently in this increase, playing host to the city’s most recent two homicides, and five across the last year-and-a-half. [Editor’s note: a 12th homicide occurred within hours of publication of this article.]

Just before its outbound terminus, the Seven makes a left-hand turn at a four-way stop intersection at Raleigh Road, the beginning of a three-bus-stops-long north-west detour around Dixie and onto Augusta and Anniston Drives. During our time on the Seven, the Kid and I would make use of all three bus stops, initially getting off at the first stop on Raleigh Road, katty-corner from where, in December 2019, 57 year old Donald Foster was bludgeoned to death one night in an Augusta Court apartment and then dumped in rural Washington County, and abutting the Raleigh/Augusta intersection where 18-year old Montaye Mullins was found last month shot and bleeding to death.

A few times—not much—we pulled the LexTran stop cord at the second stop, about halfway down Augusta Drive, across from a Valero gas station and nearly within view of the apartments on Dalton Court where a gun battle this week left one man dead and two hospitalized, the Kid and I turning our backs on both Dalton Court and the Valero to cut through the backyard of the apartments where 55 year old Lowell A. Johnson was alleged to have been shot to death in May 2020 and hopping over a rotting, partially felled wood fence into the back parking lot of Vineyard Community Church and the straight-shot, crossing guard-less walk across the morning drop-off traffic, past the awaiting teachers and principal and on through the front doors of Dixie.

But by the end, for most of Second Grade, we mostly stayed on the bus until the third Dixie stop, which is the Seven’s designated mid-route break at the intersection of Augusta and Anniston, the end of the line. The few extra minutes it took for us to arrive at the Anniston and Augusta stop allowed us to wind down any open books, drawings or cross-aisle conversations, and on measure, this third stop did not take any more time to get to school than the other two. We got use to walking the final quarter mile with fellow Dixie student Quay* and his Momma or Auntie, who like us used LexTran to get to school.

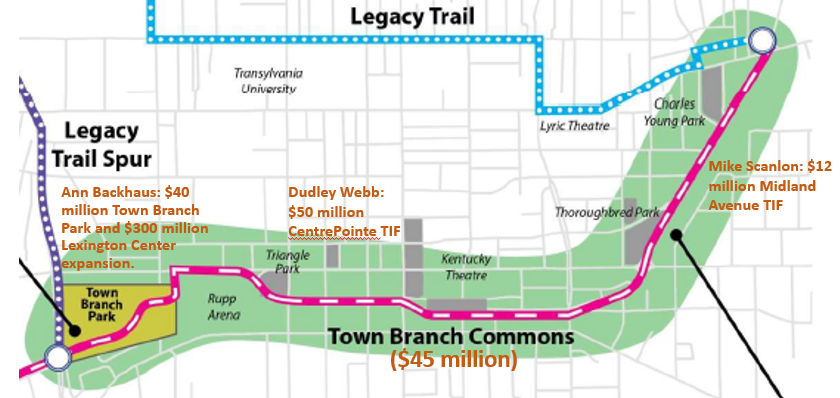

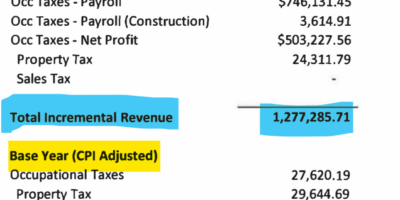

We started riding the Seven in 2016, what turned out to be the beginning of Lexington’s homicide surge, but also at a moment in city history when the early Obama-era promises of the Jim Gray administration had begun to transition into concrete budget allocations. $300 million for Rupp Arena. $75 million for the Town Branch Commons. $32 million to renovate the Old Courthouse. $3 million to complete the Legacy Trail into the East End (the final project of the $260 million dollar public investment to hold the 2010 World Equestrian Games). $15 million more for a Jim Gray donor to develop the Legacy Trail’s East End terminus. Another $15 million to help the University of Kentucky develop pasture-land along the Legacy Trail’s suburban edges.

Van Meter Pettit, son of Lexington’s first Mayor of the merged government, described the promise of such centralized investments in a 2013 Op-Ed for the Lexington Herald Leader:

Like a well in the desert, our downtown is so small and intimate that every option for maximizing its quality and economic potential is essential to pursue.

Van Meter pettit

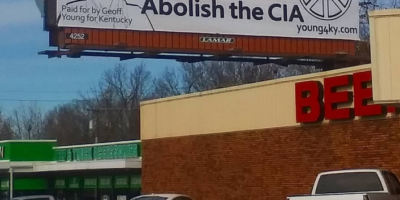

Pettit was describing the mantra of what I have elsewhere called the Make Lexington Great Again (MaLGA) movement, whose explicit goals were to devote vast amounts of public capital to fix the already-fixed parts of downtown, to connect already-connected constituencies, to trumpet the already valorized and wealthy, to leverage the newly-fashionable with the well-credentialed. The MaLGA movement was not limited to a few wealthy muckety-mucks like Van Meter Pettit living in downtown-adjacent Bell Court (though a surprising amount of MaLGA decision-making resides there).

In the mornings, the Kid and I caught the bus from our home along a North Limestone corridor (“NoLi”) that was receiving the MaLGA affections of the city. As we rode the Seven up North Limestone toward its right-hand turn onto the north Circle, we could look out the bus window and see how young business leaders and artists were opening businesses, renovating buildings and forming partnerships, most of this underwritten by established area money gobbling up nearby property and an aligning consumer class of recent college graduates and the Boomer residents of nearby wealthy enclaves (like Bell Court). Social activists joined the partnership, often settling, as with the non-profit hub the Plantory, on the grounds of these MaLGA businesses.

In a time of suburbanizing poverty and emerging urban gentrification, our MaLGA activists, business owners, consumers, and artists were all in agreement: centralize city and private foundation grant money, locate art (and artists) in nearby favored districts that feature favored civic brands (horses, bourbon, craft food, UK basketball, and art anyone?), use these revived brands to fix the East End or NoLi or the West End. Local media provided saturation coverage, devoted think-pieces on the enlightened benevolence of these actors and actions.

Alighting five days a week at Anniston and Augusta–the desert in Pettit’s formulation, a place far from the essential downtown well–the Kid and I trod the grimy underside of our city’s efforts to Make Lexington Great Again: outside New Circle, hemmed-in by I-75, the end of the Seven line, far from any $75 million bike trails, and with a dense and multicultural population anchored (like Chevy Chase’s Romany Road) around a small commercial center.

Augusta was proof that our city’s grandest civic investments and smallest community-minded engagements…bore absolutely no relation whatsoever to actual city needs. Proof, too, that the MaLGA self-image as an aware, caring—affectionate—community was in fact a psychotic sublimation of reality. If I’ve rarely batted an eye at the belligerent dumbass battie-ness of the national MAGA movement from 2017-2020, I owe it to my morning travels with the May Day Kid during a high-water mark in this city’s MaLGA batshit belligerency.

You can’t visit Augusta and Anniston and still argue for prioritizing the construction of a $75 million “commons” through already bike-able neighborhoods around Main Street; you can’t alight here, scan the non-profits operating in the Valero commercial strip, and still claim that this city engages marginalized Lexingtonians within their communities. You can’t read the homicide lists or census charts and still believe that artist housing or a competitive Thoroughbred industry or a nationally ranked state research university rates high on any list of city needs or solutions. You can’t.

After dropping the Kid off at school, I normally had about 20 minutes to kill until the next bus arrived to return me back to Lexington (my MaLGA leaders deeming a 30-35 minute route frequency as civically acceptable and, I suppose, ample demonstration of enough affection). I spent most of the Kid’s first year walking the streets that bloom around Dixie, learning how to use the different bus stops to manipulate the time and distance of my walks. I saw late Fall sunrises on the heights of Fort Sumter. Got drenched on Courtland. Grabbed coffee cakes at the Valero. Lightly explored a feeder creek for the Elkhorn’s North Fork.

Eventually, I began to skip the return bus and just jog home. Still later, I’d exit Dixie through a northwest passage on Anniston and hike to my job on Newtown Pike, an hour-and-a-half trek that had me passing Deep Springs Elementary and crossing Bryan Station near Bryanwood, skirting the High School on Eastin for a Constitution Park cut-through (by way of Northern Elementary), crossing the north Circle at Limestone, entering Broadway at the Lexington Legends stadium, and finally hitting my backstretch, Loudon Avenue, at Russell Cave Road. Taking those walks then, I remember thinking what a bummer it was that our focused attention on downtown and its nearby innards seemed to require a stark lack of affection for those people and places existing outside of it.

I look at the list of Lexington’s 2021 homicides, and I note the same thing the Lexington Herald Leader noted about 2020’s record-breaking number of homicides: they are skewing younger. The violence at the end of the Seven underscores the trend. Montaye Mullins, a Henry Clay graduate, was 18 years old when he died last month on Augusta. The murders of Lowell Johnson and Donald Foster involved three alleged perpetrators who ranged in age from 17 to 19 years old.

Both victims and alleged perps are close enough to be the parents, siblings and neighbors of the Kid’s classmates, the same gaggle of laughing, excitable kids we regularly joined on the final leg of our morning trip to Dixie and its teachers and principal at the front door awaiting our arrival. Soon enough, given current trajectory, the overlap will become more direct. Anthony “Tony” Asay was 18 in December 2019 when he beat to death 57-year old Donald Foster, old enough to be a freshman at Bryan Station High in 2016 when the Kid began Kindergarten. A fifth-grader roaming the halls during the Kid’s kindergarten year could be a rising high school sophomore this coming Fall.

Time has a way of slipping by, and before you know it, the values and patterns of the last decade, a city of subsidized wells and left-behind deserts, have raised a generation of kids into young adulthood. Future city leaders, one hopes, will begin their civic inquiries not at Main Street (or inside the Kentucky Horse Park), but in places like Anniston and Augusta, neighborhoods that are in various ways located at the end of the Lexington line.

I know from my walks around Dixie, and the Kid surely knows this, too, that her classmates are not future killers and late-night homicide victims but bright, exuberant, sometimes stubborn, often funny, loving human beings who like to joke, swing on the swings, play ball, read, marvel at the critters in their world–just like the Lexington Police Department’s list of 17-28 year old victims and perpetrators liked to do back when they trudged down Raleigh or Anniston on their way to the teachers and principal waiting for them down the road.

One hopes the next generation of city leaders are made aware of this surfeit of potential energy and capital, and to wonder at how best to engage it.

*Name has been changed.

Dave

Perhaps include the silly PDR Program that has wasted more tax money than any you listed.

Dana

The Herald-Leader reported another homicide on Friday morning; that would make 12 this year. 12 murders in 99 days puts Lexington on pace for 44 killings this year, and the long, hot days of summer haven’t gotten here yet.

But at least it isn’t Philadelphia!