Hatchling of the Chickasaw

By Ed McClanahan

This is part two of an intermittently serialized memoir by Ed McClanahan that takes as its working title “Hatchling of the Chickasaw: A Kentucky waterways story.”

My father, Eddie (Edward Leroy, officially), was born and raised—or, as they liked to say around there, “reared”—on a rocky little hillside tobacco farm in a rural community called Johnsville in Bracken County, Kentucky, about 50 miles east of Cincinnati, within a couple of miles of the Ohio River. As a boy, he swam and fished in the Ohio in the summertime, and even crossed it on the ice a few times, in bad winters. My mother, Jessie Poage, grew up in Brooksville, the county seat. During their courtship, she was a schoolteacher in Neville, Ohio, to which she commuted via the mailman’s rowboat. My own earliest clear memory is of moving out of our house in Augusta, a Bracken County town on the Ohio, in the flood of 1937 … in a rowboat. I was five years old, and I had the chickenpox. We three wretched refugees—Eddie and Jessie and this meager, itchy little fellow they called “Sonny”—disembarked at the soonest opportunity and immediately skeedaddled to Brooksville, the highest point in Bracken County, where we stayed for the next ten years, high and dry.

But the Ohio was never far away. Sometime around 1940, my dad and his brother Don and their cousin Charlie McCarty had partnered up with a jackleg carpenter named Punch Vermillion and built a little fishing camp (maybe the world’s first timeshare) on the riverbank at Bradford, near Augusta, fifteen miles or so from Brooksville, and my folks and I and the other partners and their families spent great chunks of our summers there during most of the 1940s. It was my favorite place under heaven: a broad river bottom, a sandy riverbank overhung with great, grieving willow trees, a serene river flowing before them like a benediction.

Our camp was a humble three-room board-and-batten ensquatment beneath the lowering canopy of willows. No electricity, no running water; we had a privy out back in the cornfield (during the war, it became a hempfield) and an icebox and a kerosene cookstove and kerosene lamps, and the grown-ups hauled water and ice from town once a day. The building itself was basically just a shell, a big tin-roofed wooden tent on stilts, the riverbank sloping away beneath it. There was a large sleeping room with a couple of iron bedsteads and two or three iron bunkbeds and half a dozen cots (all available on a first-come, first-served basis), a kitchen featuring the aforementioned appliances plus a vast array of cast-iron skillets and cast-off crockery and tableware, and a long screened-in porch that stretched all the way across the front of the building and accommodated a huge, rough-hewn picnic table and two long benches. Each room had its own screendoor (to facilitate access to the privy, whose irresistible appeal kept the screendoors slamming day and night), and all the windows were screened as well, so that, in the sweltering Ohio Valley summertime, our camp had the best air-conditioning in Bracken County.

There were always lots of kids to run with; cousins and second cousins abounded, in company with the numerous spawn of the prolific Punch Vermillion. The cousins were mostly okay, but older, and pretty much inclined to ignore me. I tended to be puny anyhow, so that left me easy prey for the Vermillions, a pack of bloodthirsty little urchins who terrorized me for most of the first couple of summers we went camping there. Sometimes I brought along one or another of my small-fry Brooksville homies, in the vain hope that they’d stand with me against the teeming Vermillions, but the treacherous little ingrates all too often went over to the enemy. Which meant, unhappily, that the ranks of the punies were usually reduced to one, namely me, Little Sir Puny, and also that even though I was at My Favorite Place Under Heaven, I was often in utter, abject misery.

That all changed the summer I was eight—1941—when I learned to swim there, the hard way: my dad took me out in a rowboat and pitched me in the river. Tough love, sink-or-swim variety. I resented the hell out of it at the time, and I still do. Nonetheless I did make it to shore, sputtering and bawling, and, mirabile dictu, from that day forward I could swim! I was no Johnny Weissmuller, granted, but I never drowned once.

Now here’s an odd but salient fact about country kids in those days: By and large, we couldn’t swim. Girls hardly ever even tried (it wasn’t quite proper), and for most farm and small-town boys the only waterholes available were shallow creeks and ponds, fine for paddling around in but not so good for actual swimming. From Brooksville, the nearest swimming pool was in the next county, twenty miles away. (My mother and her seven siblings all grew up in Brooksville, and none of them could swim a lick, although one of my heftier aunts could float like an empty rainbarrel.) Unless you lived near the Ohio, you’d have had to jump down a cistern or stick your head in a horse trough to find water in Bracken County deep enough to drown in. Wading and dogpaddling were the aquatic engines of choice.

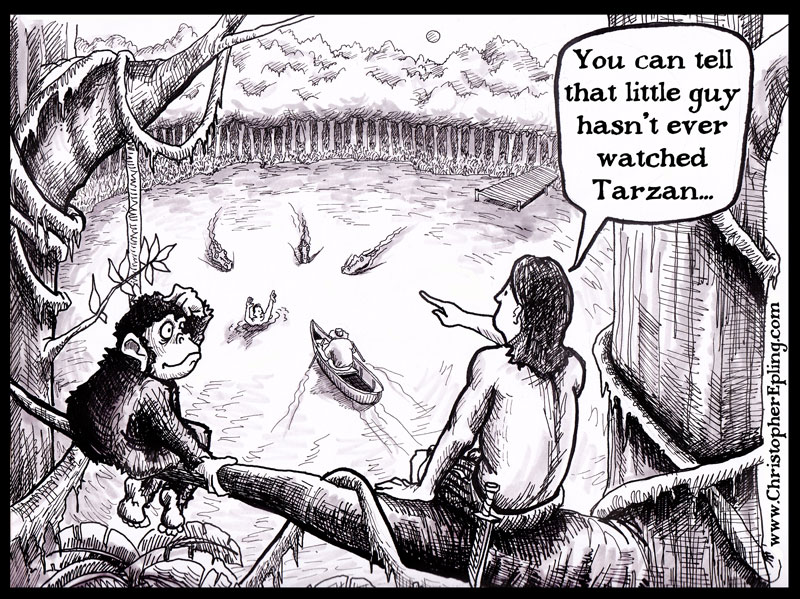

Although I don’t suppose my father ever saw a Tarzan movie in his life—he didn’t have much use for movies— his swimming style surely owed something to Johnny Weissmuller. Alone among the men his age of my acquaintance, my dad employed an overarm stroke and a flutter kick; a crawl. He gently rolled his shoulders with each stroke, and elegantly flicked his hands—feathered his oars, so to speak—instead of flailing at the water like a human paddlewheel. Unlike Tarzan, he steadfastly kept his face above the surface, rigidly fixed on the immediate future, as though he were his own figurehead. (I regarded this little idiosyncrasy as my father’s personal refinement of Tarzan’s technique, and marveled that Johnny Weissmuller hadn’t adopted it himself, if only just to guarantee that he wouldn’t run head-on into a crocodile.) I have no idea where my dad learned to swim that way—his older brother Don was a wader all his life—but locally the style was very distinctive, and he was widely (if, as we shall see, not quite correctly) regarded thereabouts as an excellent swimmer.

Intuitively, I understood these developments perfectly well even before my dad pitched me in the river. Okay, I’m cheating here a little bit: in fact, he gave me a couple of rudimentary swimming lessons and concluded that it was time for me to try it on my own—and then he pitched me in the river. Anyhow, by the time I sputtered ashore, mad as a wet hatchling, I had already determined that since I was now, albeit reluctantly, forevermore a swimmer, I was by god gonna swim like Johnny fucking Weissmuller … and my goddamn daddy.

(All this bad language, needless to say, is strictly retroactive. But had I been a more accomplished blasphemer at the time, those are among the milder terms with which I might’ve expressed myself.)

Well, it took a few days, but eventually I got the overarm-and-flutter-kick business down pretty good, and I could put my face in the water too, although I never did quite figure out the breathing thing. Obviously, Johnny and my dad had each developed his own individual breathing technique, so I simply did likewise—which is to say I held my breath and shut my eyes and launched myself forward, facedown, as blindly purposeful as a torpedo, for as many highly stylized Tarzanian strokes as I could squeeze into a single breath, meanwhile flutter-kicking like a demented horizontal ballerina; I surfaced when I absolutely had to, gasped aloud as though I were drowning, then shut my eyes again and plunged ahead, crocodiles be damned.

Nonetheless, unorthodox though it was, my new mastery of the aquatic arts rendered me, as it had my father before me, the best swimmer in my age group at the McClanacamp, and elevated my status amongst my juvenile campmates to unprecedented heights. Vermillions? Let the vicious little tadpoles perish in my wake!

Except for roller skating (I was destined to become, in the prime of my adolescence, a devilish fine roller skater), learning to swim would remain my proudest athletic accomplishment until the day, years later, when I threw an egg through the wind-wing of a moving car. But that’s another story, one I’ve told too many times already.

Leave a Reply