The continuing struggle of garment workers

By Beth Connors-Manke

If you view history as a discrete set of events, then the similarities are eerie. March 1911: 146 garment workers, many of them young women, die in a factory fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. November 2012: 111 garment workers, many of them women, die in a factory fire at the Tazreen Fashions Company. Neither building had a sprinkler system, although the technology was available. Both factories had fabric stored in ways that led easily to raging fires; in both factories, escape routes were blocked and workers were hindered from speedy evacuations. In each case, workers had protested labor conditions before the disasters.

However, if you view history as a long struggle for progress and social justice, the similarities are depressingly tragic. One hundred years after the Triangle fire in New York City, the Tazreen blaze in Dhaka, Bangladesh, again finds Americans thoughtlessly complicit in deadly working conditions for garment workers. It may not have happened in one of our industrial cities, but the Tazreen fire still occurred in our supply chain—it is still a product of our economic structure and attitudes about labor.

Triangle

Exploitation seems a mild way to describe the labor conditions for U.S. garment workers in the early twentieth century. Work weeks stretched longer than 50 hours; employers charged workers for electricity, needles, and material they needed to produce clothing for the company. Fire escapes were of dubious construction, and emergency exits sometimes partially blocked. Not to mention that some workers were continually held under suspicion and treated like pilfering cattle: at Triangle, at the end of each shift, employees were corralled and then released one by one through a narrowed corridor so they could be inspected for stolen goods before they went home. (Think post 9/11 airport security—but stationed at your workplace.)

New York garment workers, who were often Jewish and Italian immigrants, knew the conditions were unjust and untenable. Between November 1909 and February 1910, thousands went on strike, demanding more reasonable labor conditions and better safety precautions. These men and women, by and large, found few improvements when they eventually returned to work. Public, private, and judicial anti-labor sentiment—along with the nativist climate—proved fierce, leaving company owners with the upper hand. According to scholar Elizabeth Burt, when newspapers covered labor strikes, journalists tended to tell the story of “labor agitators,” “socialists,” and “anarchists”—all groups believed to be a threat to America. Generally absent in news stories were descriptions of the deplorable working conditions.

But when New Yorkers were forced to witness the outcome of purposely derelict safety precautions—when they watched women, hair and clothes aflame, jump out of eighth and ninth story windows—attitudes shifted. The fire broke out on a busy Saturday afternoon, so there was no shortage of bystanders to the carnage. During the week following the disaster, papers in New York and across the country ran hundreds of articles filled with graphic descriptions and eyewitness accounts of the fire.

From the Chicago Tribune: “Within a few minutes after the first cry of fire had been yelled on the eighth floor of the building, fifty-three bodies were lying, half nude, on the pavement. Bare legs in some cases were burned to dark brown and waists and skirts in tatters showed that they had been torn in the panic within the building before the girls got to the windows to jump to death.”

Having watched a girl come to a window ledge and then pause, a bystander told a reporter: “Then she jumped. She whirled over and over, a streak of black gown and white underclothing, for nine floors and crashed into the sidewalk.”

In under a half hour, the fire was extinguished, bodies laid out on the street, and piles of trapped and flayed workers found against interior doors.

The owners of the Triangle Waist Company, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, escaped the blaze. While they were hammered in the press, they were eventually acquitted of negligent homicide for locking the doors to the back stairway. The justice system certainly failed, but the catastrophe led to more successful organizing and, eventually, better laws. Surely, though, that was cold comfort to relatives who gathered at the morgue, wailing in Yiddish, Russian, and Italian; to the 10,000 mourners who processed down Fifth Avenue during the mass funeral.

Tazreen

Google images for the Tazreen fire, and you’ll find faces of grief-stricken mothers; rows of rectangles awaiting burned bodies; angry workers clogging the streets to show their resistance to a system that doesn’t value their lives. (Fires have been common in Bangladeshi factories over the past decade.) In short, you’ll see photographs that make you—albeit at a remove—a witness to the suffering caused by the Tazreen fire.

The tale of the blaze at the eight- or nine-story (depending on your source) Tazreen Fashions factory reads too much like the Triangle disaster—enough so, that it doesn’t take a genius to link the two. The new twist on the story is the layer upon layer of international corporate greed and professed blindness that have supported deadly conditions at garment factories.

The American company under the most scrutiny at the moment is Walmart, whose Faded Glory clothing line was being made at Tazreen. Walmart is, of course, playing the shell game as it denies responsibility; the company claims it had broken relations with the factory, but one of their suppliers had, against Walmart policy, continued to subcontract there.

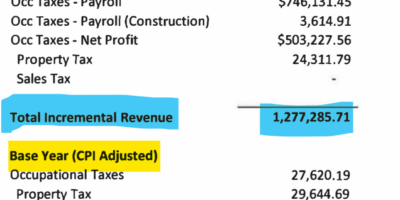

Nonetheless, Walmart and other international enterprises have exerted downward pressure to keep costs low in factories in Bangladesh. The New York Times reported that during a 2011 meeting, international companies, including Walmart, discussed safety concerns with Bangladeshi government officials, nongovernmental organizations, and factory owners. After a Walmart representative noted how extensive the needs are—4,500 factories would need expensive modifications—it was concluded in the meeting minutes that “It is not financially feasible for the brands to make such investments.”

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium, estimates that it would cost companies pennies per garment—less than a dime—to help instate better safety practices in factories in Bangladesh.

The Tazreen fire raged longer than the historic Triangle blaze, reportedly lasting all night. Hopefully, that will not prove to be a metaphor for the time it will take to ensure Bangladeshi garment workers aren’t toiling in cinderboxes. Those who have been made witness to the devastation at Tazreen—either in person or through accounts of the tragedy—should insist that change comes quickly. Let the injustice and suffering motivate change, as it did with the Triangle disaster. There will be excuses (“our supply chain is too complex for us to know where our garments are being made”), just as there were excuses that led to Blanck’s and Harris’s acquittals in the Triangle trial. However, that doesn’t mean change can’t happen.

Be a witness: The University of Kentucky chapter of United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS) will be hosting Tazreen workers on Wednesday, February 13, in room 249 of the UK Student Center from 4:30 to 6:30pm. The Tazreen workers will speak from experience about the importance of independent monitoring.With an independent labor rights monitoring system, factory fires can be prevented and labor rights upheld. The workers will speak about what independent labor rights monitoring, like the Worker Rights Consortium, would mean for UK affiliation and fire safety at the factories it sources from. Information on the event can be found on Facebook; search “Tazreen Garment Worker Tour.”

Leave a Reply